Green Lantern #50-#51

DC Comics, March, April 2016

Writer: Robert Venditti

In his book “Come in Alone” (AIT/Planet Lar, 2001), British writer Warren Ellis furiously laments the brand loyalties of readers of superhero comics, such that some of them publicly admit on message boards that they would rather read poorly-written material about favourite characters than suffer fundamental changes to those characters. In his book Mr Ellis lambasts readers of this ilk, describing them as essentially responsible for the creative malaise and commercial degeneration of the American comic book industry.

Mr Ellis did not take this assessment to the next step: that such leniency by fans in respect of certain longstanding character properties gives writers and editors employed by publishing companies a leave pass in respect of quality writing. This is most evident in “Green Lantern” #51 and #52.

The writer, Robert Venditti, spends issue 50 of this 2016 series exploring a showdown between an historical, villainous version of Green Lantern and the contemporary version. The villainous version has an interesting history. In 1994, another writer, Ron Marz, was directed by editors to write a highly controversial Green Lantern storyline. The much-beloved but stale title character had aged, been allowed to turn grey-haired, and had perhaps become crusty to the point that it was no longer capable of being conceptually appealing to young readers – which teenager wants to read the adventures of someone who looks like their dad? Most importantly, sales had slumped and the publisher decided to reverse that with a radical plan.

In issue 50 of the 1994 series, Mr Marz sent Green Lantern over the brink of sanity as a consequence of the destruction of his home town (called Coast City). Green Lantern then killed his friends and colleagues in the Green Lantern Corps, and became a powerful villain. The character then became known, oddly, as Parallax.

This treatment of a character created in, and essentially unchanged otherwise since 1960, was intensely unpopular in 1994 and the years following. Readers correctly saw it as a disrespectful, hamfisted editorial strategy of introducing a new, young, and fun character into the role.

But the basic concept was intriguing: what if a mainstay property, needing a stark and jolting brand refresh, became one of its continuity’s greatest threats? Regrettably fan backlash was so intense that the publisher lost its nerve and the full potential of this development was not explored. The original character underwent a form of fatal rehabilitation when, in a subsequent 1996 story (a mere two years later), Parallax sacrificed himself as part of a convoluted plot device to reignite the sun.

Parallax’s insanity was then blamed not upon being stressed to the point of breaking, but instead upon being prey to a sentient and menacing space parasite. As a dour capstone to that ridiculousness, Parallax’s grey hair was described a symptom of parasitic possession rather than an indicia of aging. It is laconic to say that this meant the character still had youthful appeal after all. The original character was, through an extremely convoluted plot device, then reintroduced into the role of Green Lantern in 2004, the youthful stand-in finally displaced after a decade-long stint.

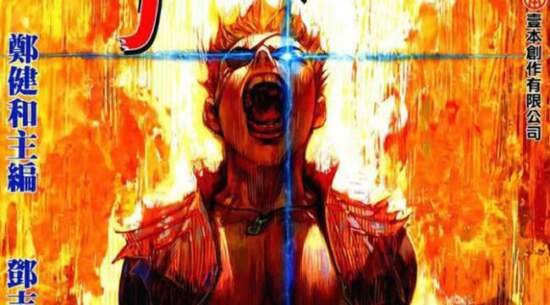

Issue 50 of this current 2016 series brings an alternative dimensional Parallax to Earth, where Coast City is not destroyed. Parallax confronts the current version of Green Lantern, who for complicated reasons is on the run and is dressed like a paramilitary hobo. The two inevitably fight, but the issue contains some surprisingly poignant scenes whereby Parallax recognises his relatives but cannot comprehend their existence.

The return of such a controversial character as Parallax is potentially exciting. Mr Venditti ends the story by having Parallax fly off in a rage. Green Lantern experiences a strange power surge, but vows to deal with Parallax. Issue 51 should have perpetuated or concluded this plot.

But instead, Green Lantern is next shown in space confronting some newly introduced, ruthless space mercenaries. There is no conclusion to the episode with Parallax. Readers are left scratching their heads, wondering if they had missed an issue or two.

Does the blind character devotion Mr Ellis describes in his book empower the publisher, the editors, or the writer to entirely derail a plot knowing that the next, entirely unrelated issue will sell anyway?