The biblical adage that nothing is ever new under the sun seems especially true in comic books. This phenomenon is sometimes cast as express homages, sometimes as sneaky or blatant efforts to piggy-back on goodwill, and sometimes as part of the creative rush to tap into the prevailing zeitgeist.

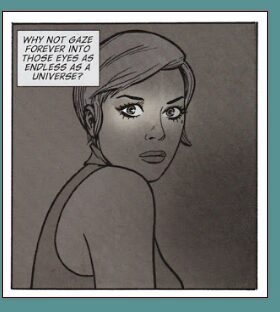

“Vertical” (published in 2004) was the last of the special formatted releases to celebrate the tenth anniversary years of DC Comic’s imprint, Vertigo. It was written by Steven T. Seagle with art by Mike Allred. The text and the art pay homage to Andy Warhol, most obviously in the excerpt above. No doubt to mitigate risk under the Lanham Act for implying an endorsement of affiliation between the comic and Warhol’s personality rights, Warhol, as a character in the comic, is referred to only as “Andy”, but lives in a place called “The Factory”, has bright blonde hair, and is clearly regarded by the characters as a shaper of opinions and style. All of this describes Warhol the person.

Mike Allred’s engaging pop art style of drawing is showcased in the clothes and hairstyles of the characters. It also uses as a stylistic vehicle a comic book genre which hadn’t been in prominence since the 60s – the comic book love/romance genre.

The art is notably avant garde. Reading the story itself is also like looking at a roll of film – the scenes are in squares and each looks like a film frame.

One character jumps from a building, and the feeling of motion is assisted by the elogated, vertical orientation of the experimentally formatted (tall, thin) comic book. The reader gets a real sense of the character falling which would not be as obvious within the limitations of a regular sized comic book. The sense of falling was intentional: in a 2004 interview for Comics Bulletin (http://comicsbulletin.com/news/107216212750771,print.htm ) Seagle says he “devised a way to use the falling action of the reading system thematically”, and Allred says the book has “mercurial feeling the way it all feels pulled down by gravity.”

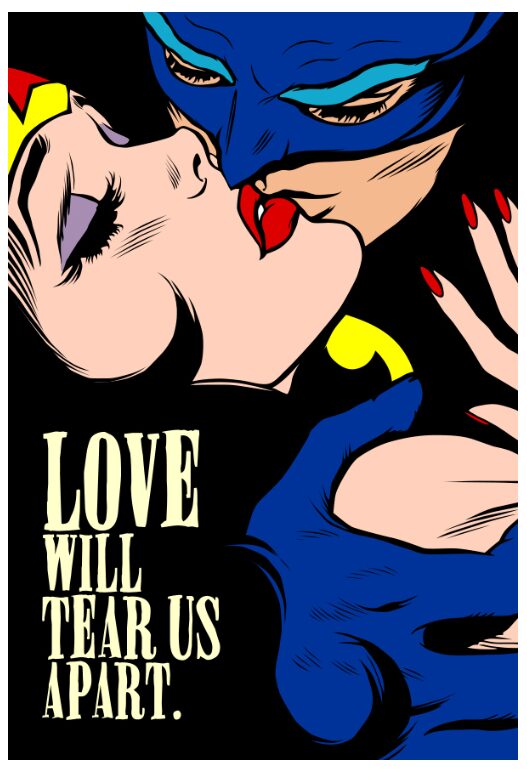

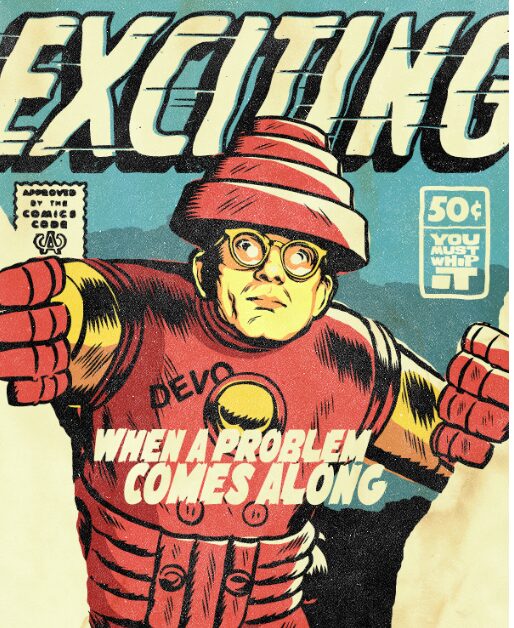

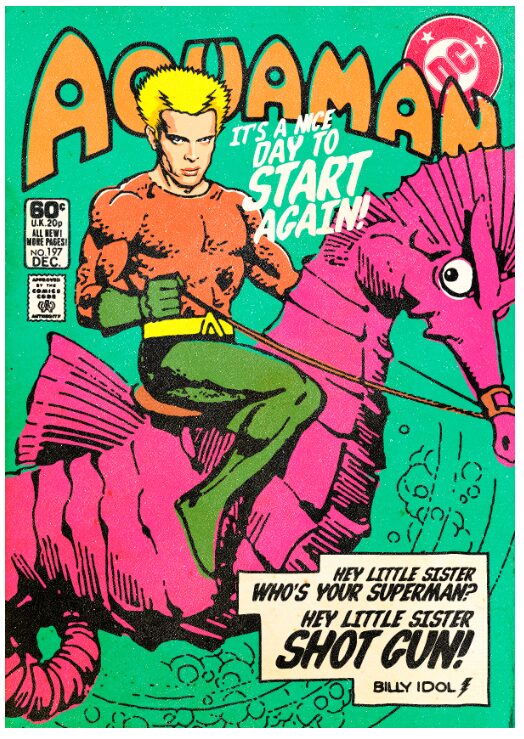

Vertigo and its parent raided Warhol’s techniques and identity for Vertical in 2004. More recently, a Brazilian art director with the nom de plume of “Butcher Billy” (www.butcherbilly.com) has done something similar but in a more brash and humorous way. Butcher Billy by mashing together 80s post-punk icons with DC Comics’ and Marvel Entertainment’s main character assets.

An interview in 2014 cites Warhol as an influence. But Roy Lichenstein – also quoted as an influence – is much more obvious.

Here are some examples:

Butcher Billy’s works are for sale. The pitch on his agent’s website notes his “subtle questioning of pop culture using pop art as his medium is a juxtaposition in itself, yet in their own unique way all his images seem to make sense.” But is it, or is it more akin to the criticism often levelled at Roy Lichtenstein – it isn’t an homage, but instead it is swiping?

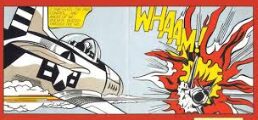

This is an image of Lichtenstein’s famous work, “WHAAM!”, worth tens of millions of dollars and owned by the Tate in London. Lichtenstein adapted the art from an “All American Men of War” comic published in 1962, and illustrated by Irving Novick. The work was finished by Lichtenstein in 1963.

In an interview with the BBC Culture website, art historian Richard Morphet is quoted as saying, “I continue to be astonished that people in the ‘60s thought – as some still do – that there is no difference between Lichtenstein’s source image and the finished painting.”

In the same BBC article, Dave Gibbons, a well-known British-based comic book artist whose works include DC’s Watchmen and the 2000AD’s Judge Dredd, disagrees: “We have a term in the business called swiping… When you are stuck for an idea, you riffle through your comics, and you trace what somebody else has done. A lot of Lichtenstein’s stuff is so close to the original that it actually owes a huge debt to the work of the original artist. But in music, for instance, you can’t just whistle somebody else’s tune no matter how badly without crediting or getting payment to the original artist.” If Gibbons is correct, DC has engaged by way of Vertical in exactly the same sort of swiping that Butcher Billy has engaged in by in respect of DC’s assets.

But the article goes on to note;

“Comparing the source for Whaam! with the finished painting banishes the hoary idea that Lichtenstein profited on the back of the creativity of others. Lichtenstein transformed Novick’s artwork in a number of subtle but crucial ways. In general, he wanted to simplify and unify the image, to give it more clarity as a coherent work of art. For this reason, he removed two extra fighter jets to the right of the original panel. He also got rid of the lump of dark shadow representing a mountainside that was an ugly compositional mistake to the left of Novick’s picture. The result is that the two panels of Whaam! feel much more evenly balanced, producing a satisfying and well-structured visual effect.”

By this rationale, both Marvel and DC should have no issue with Butcher Billy, nor should Warhol’s estate have any issue with DC’s Vertical.

But DC Comics sometimes doesn’t have much of a sense of humour about these things.

In 2013, Warner Bros., the owner of DC Comics, commenced proceedings against a car customising business named Gotham Garage. The business produced custom replicas of automobiles that are featured in films and TV shows, including Batmobile replicas for USD90,000 each.

The Court found for Warner Bros., citing that the Batmobile is protected by copyright because it is a character in and of itself, as a “consequence of the Batmobile’s portrayal in the 1989 live motion film and 1966 Television series.” Other factors that contributed to Warner Bros.’ case include the fact that Gotham Garage used DC’s Batman-related marks in the advertising for their services, and that the bat design marks are “distinct.”

The decision has been appealed. Parody wasn’t apparently raised by Gotham Garage – the idea of middle aged overweight men (undoubtedly the target market for Gotham Garage) driving the Batmobile seems vastly humorous.

In a separate 2005 decision, DC Comics v Pan American Grain Mfg Co Inc,, the plaintiff, DC Comics, owned the trade mark rights to Kryptonite, the famous green-glowing mineral which can fatally weaken Superman. The registration for Kryptonite covered only t-shirts and novelty items. The defendant had wanted to use the term, Kriptonia, for a prepared alcoholic fruit cocktail drink.

DC Comics filed an opposition to the defendant’s application for trade mark. DC Comics claimed that it had focused enormous attention, effort and investment ‘to develop the Superman mythos, including the character, his associates, his world, and other indicia associated with him.’ It successfully asserted that ‘Superman has become associated with certain symbols and indicia which in the public mind are inextricably linked with the Superman character and which function as trademarks, both for literary and entertainment works featuring Superman and for various goods and services for which one of these indicia is Kryptonite (a rock from Superman’s home planet, Krypton, which has a debilitating effect on his powers)”.

Butcher Billy’s works are entertaining and funny: the unexpected mash-ups of 1980s comics covers with 1980s musicians, with lyrics in Comics Sans, are creative output which should be encouraged. As a parody, the artist indulges in freedom of expression by way of parody which is both more blatant and somehow more original than the stylistic homage of Vertical or the subtle recalibrations of Lichtenstein.