“Dejah Thoris” # 1 (review)

Dynamite Entertainment, December 2015

Writer: Frank J Barbiere

Review by DG Stewart, 24 February 2016

US comic book publisher Dynamite Entertainment have sensed the change in the demographics of comic book readership, and tried to refresh some of its licensed female character concepts by:

a. employing female writers, who are likely to write female characters as women rather than as objects of desire (and in turn, lending an air of respectability to the title – female writers are more likely to be identified by their full names in promotional copy so as to make it plain that a woman is writing the script); and

b. covering the bare skin and ample breasts of characters best known for titillation of a male readership. “Red Sonja” (Dynamite Comics), “Vampirilla ” (Dynamite Comics), “Wonder Woman” (DC Comics) and “Tomb Raider” (Dark Horse Comics) are titles each best known for displaying a manifest abundance of cleavage on their respective comic book covers. But in 2016 these characters feature a new modesty. DC Comics’ flagship character Wonder Woman now wears very modern-looking full body armour. Red Sonja’s small chainmail bikini top is gone and replaced by a chainmail shirt. Vampirilla’s notoriously skimpy red swimsuit is now replaced by a red Steampunk riding suit. Lara Croft, the character featured in “Tomb Raider”, now wears practical attire for exploring, instead of a low cut singlet.

This change in direction for “Vampirilla” and “Red Sonja” was announced by Dynamite Comics in October 2015. The press release from tbe publisher made it clear that this was intended to include “Dejah Thoris”.

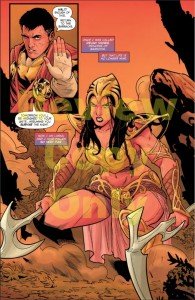

But it did not. Scripted by a man, the title character runs about wearing only a shell bikini to cover her large breasts, together with a loin cloth, while sword fighting. This is however a step up from Dynamite Entertainment’s previous run of publishing “Dejah Thoris”, in which the covers looked more like Playboy Magazine than a comic book.

“Dejah Thoris” is a comic book spin-off from a series of pulp science fiction adventure books written between 1912 to 1950 by acclaimed fantasy author Edgar Rice Burroughs (most famous, perhaps, as the creator of “Tarzan”). The novels are set on Mars, called “Barsoom” by the inhabitants, and revolve around the adventures of an ageless Confederate soldier, John Carter, who has mysteriously travelled to Mars and achieved through martial prowess both the title of “Warlord” and the heart of the crown princess of the city of Helium, Dejah Thoris.

The stories run thick with both blood and testosterone, featuring four-armed Martian warrior races, wars, and intrigue, and, while holding a place in the hearts of many older science fiction buffs, are very old-fashioned and lacking in any sophisticated dialogue.

US media giant Disney made a film in 2010 called “John Carter” based on the novels, which failed dismally at the box office. The estate of Edgar Rice Burroughs is very active in licensing its properties through a commercialisation entity called ERB Inc. And so when the likes of British writer Warren Ellis involves Tarzan in his comic “Planetary” (2004) or British writer Alan Moore involves John Carter in his comic “The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen” (2002), both do so in a very circumspect way, making only oblique references to the characters for fear of running foul of Burroughs’ estate’s licensing activites.

Mr Moore wrote John Carter very sympathetically in “The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen”, making it clear that the Warlord of Mars was a Southerner, shadowed by his friend the green-skinned warrior Tars Tarkis. He is described as an apparent widower or perhaps divorcee, signalling that the grand love affair, the core concept of the decades of publishing of the pulp novels, between the roguish Earthman and the most beautiful woman on Mars was at an end. The dialogue is scant, skilful, and fluid. Carter, an intelligent and thoughtful general, is depicted both at rest and at war. Dejah Thoris’ absence clearly pains the character.

Mr Barbiere takes an entirely different approach. John Carter is shirtless, stiff, and a little pompous. Dejah Thoris is kind to her servant girl, but is otherwise proud and shallow.

The character’s reaction to her father’s disappearance and presumed murder is almost devoid of any real emotion – there is no sense of panic or fear for the man’s safety from either his daughter or his son-in-law.

When the allegation is put to the princess that she is in fact adopted, Mr Barbiere has the character recollect a repressed and partial childhood memories which prompt her to break out of jail and make for the badlands. It is a clunky plot.

And in that regard it is true to its source material. Mr Burroughs’ writing was stilted and grinded through poor characterisation, rushed plots and dialogue which to contemporary readers is childish and cringeworthy. Mr Barbiere’s text demonstrates very clearly the plots of Barsoom are terribly dated.

The excitement of the novels, much of what defined and made the John Carter novels compelling is the sense of strangeness and wonder. But these elements sadly are entirely absent from this comic. There are no alien monsters – no terrifying lion-esque Banth, no exotic horse-substitute Thoats. There are no valiant but savage allies in the form of the Green Martians, a critical part of the original novels (Dejah Thoris’ children, Cartharis and Tara, are also not evident). There are no antigravity warships, no “radium bullets”, and no advanced technology. The story could just as easily have been set in any outlying Middle Ages kingdom.

The absence of outrageous alien-ness is a wasted opportunity. In the novel “The Chessmen of Mars” (1922), Mr Burroughs introduces the vile Kaldanes. These are sentient creatures consisting of a head but for six spiderlike legs and chelae. They Kaldanes have bred the Rykors, a complementary species composed of a human body but lacking a head. A Kaldane rides the headless neck of a Rykor, controlling the Rykor’s body via the spinal cord. It is chilling and creepy. The books are filled with such horrors. Mr Barbiere has not harnessed any of these concepts in this title.

More fundamentally, it is a shame that Mr Barbiere chose not to add his own voice to the characters. Perhaps there was an editorial oversight by Burroughs’ estate which mandated that the comic did not depart from the essence of the original texts. If that is the case, then there has been a seriously poor estimation of the sensibilities of modern readers.