In a peer-reviewed article entitled “Smoking in Movies: Impact on Adolescent Smoking” written by James D. Sargent MD (Adolsc Med 16 (2005) 345-370, there is a startling finding:

“Adolescent never smokers who nominated a star who smoked on screen were 1.4 times more likely to take up smoking over the 4-year follow-up period, even after controlling for other baseline influences… [there is] strong… epidemiologic evidence of a link between exposure to movie smoking and adolescent smoking. It is notable that the estimates of the effect of seeing movie smoking on smoking initiation in both longitudinal studies were almost identical to estimates that were obtained for the cross-sectional samples. This suggests that continued exposure to movie smoking and its effect on adolescent smoking persists over time.”

If there is to be any conclusion from this survey, it is that the frequency of the depiction of smoking in comic books after decades of public education on the risks of smoking tobacco has not diminished, save in the US.

1. Smoking in Japanese manga

There have been studies on the impact of the portrayal of smoking in Japanese manga. Here are some extracts of conclusions

a. “Indeed, a preliminary study from the University of Tokyo showed that, of the top four selling boy’s comic magazines (each magazine typically carrying 20 titles of serialized manga stories) in Japan, smoking depictions appeared in 20 of the 87 titles, and teenage smokers accounted for 17.6% of the smoking depictions. Thus, there is a significant concern that the Japanese children and adolescents receive greater exposure to smoking depictions than their American counterparts.” (Masahito Jimbo, “Japanese Manga and Smoking:”Puffing Away”, International Institute Journal University of Michigan, Volume 2, Issue 1, Fall 2012)

b. “Tobacco events appeared in 10 of the 70 titles in girls’ comics, 22 of the 60 in women’s, 20 of the 87 in boys’, and 24 of the 85 in youths’; in 42 (0.6%) of the 7103 panels in girls’ comics, 97 (1.2%) of the 8170 in women’s, 105 (1.3%) of the 7835 in boys’, and 173 (2.7%) of the 6399 in youths’. Smoking appeared 396 times in 386 panels; paraphernalia and conversation about smoking appeared in 31. Teenage smokers accounted for 17.6% and 6.1% of smoking depictions in boys’ and youths’ comics, respectively (table 1). Smokers in their 20s and 30s were likely to appear in women’s and youths’ comics. Female smokers were more likely to appear in women’s comics than in the three other types of comics. Smokers in youths’ comics were likely to be main characters. Smoking was rarely depicted negatively. The majority of tobacco products were cigarettes.” S Nakahara, M Ichikawa, S Wakai, “Smoking scenes in Japanese comics: a preliminary study” Tob Control 2005;14:71 doi:10.1136/tc.2004.009597

Bleach, “The Cigar Blues Mix”, 2002

Mr Jimbo’s 2012 article notes that “In 2006, the Japan Society for Tobacco Control filed an official complaint to the creator, the publisher, and the TV production of Nana, a manga about a group of aspiring musicians in late teens and early 20s that was turned into TV anime, with a wide audience consisting of teenage girls and women in early 20s. In it, virtually every character smokes real brands of cigarettes, leading the tobacco control society to insist that it would lead to impressionable youth following suit. The creator, the publisher, and the TV production all politely wrote back, saying essentially, “Tough luck.””

Morel Mackernasey, a character in Japanese manga “Hunter X Hunter”. This character is particularly reliant upon smoking as a form of super-power.

US Comics

Marvel Comics’ Storm

In 2001, the New York Post published a report that Marvel Comics President Bill Jemas and Editor-in-Chief Joe Quesada had decided to ban smoking in the company’s super-hero titles. “Villains can still smoke, but that’s OK, because villains are stupid,” Quesada told The New York Post in an interview, elaborating that the decision was instituted because it was the “responsible thing” to do.

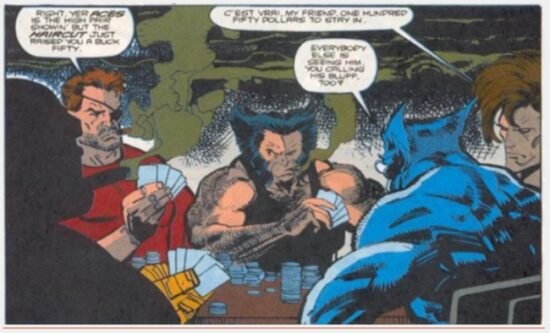

Mr Quesada noted in the article that the “main culprit” was the popular Canadian anti-hero Wolverine, of the company’s best-selling X-Men titles. Wolverine is a recidivist cigar smoker.

“[Wolverine] is a role model for some kids and he shouldn’t be smoking,” Quesada said. “Besides, the healing factor would keep him from getting addicted to nicotine anyway, so it doesn’t even make sense for him to smoke.”

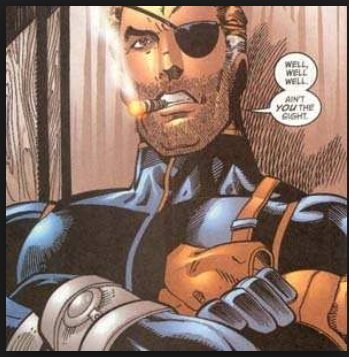

The no-smoking ban also affected the depiction of smoking by another “Uncanny X-Men” character named Gambit, as well cigar-smoking spymaster Nick Fury, from “Nick Fury Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D.” (amongst many other titles), and the cigar-smoking hero Thing of “Fantastic Four”.

Mr Quesada is described as a non-smoker who lost his grandfather to smoking-related emphysema and experienced his father suffering a collapsed lung from smoking. The New York Post quoted Mr Quesada as saying “It’s a nasty habit that’s affected my life in a tragic way”.

Wolverine, (Marvel Comics 1992)

Unhappy reader reaction to the smoking ban in Marvel Comics has been long-lived.

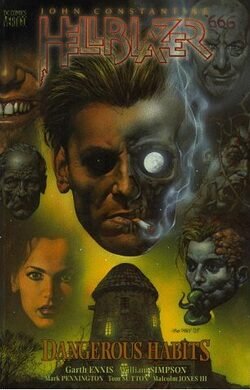

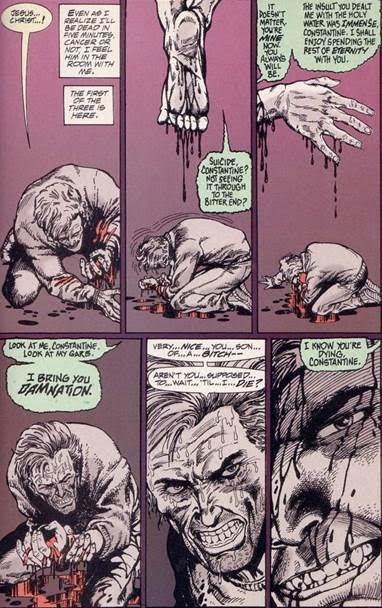

At DC Comics/Vertigo Comics, a major character, John Constantine, described by creator Alan Moore as a “blue collar warlock”, was depicted as contracting lung cancer as a consequence of smoking in the story arc “Dangerous Habits” (Hellblazer #41-#46, 1991).

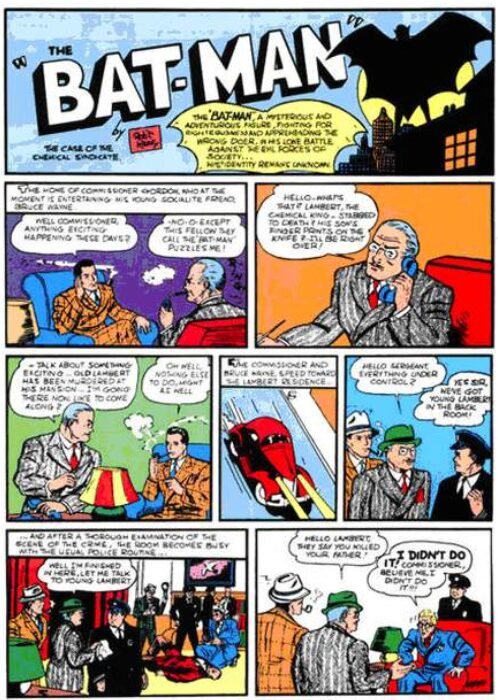

Other examples of superheroes smoking, as depicted in US comic books, and dating back as early as 1939, are listed below.

DC Comics’ Batman – “The Case of the Chemical Syndicate” (Detective Comics #27, 1939)

Marvel Comics’ Reed Richards of the Fantastic Four (Fantastic Four #3, 1961)

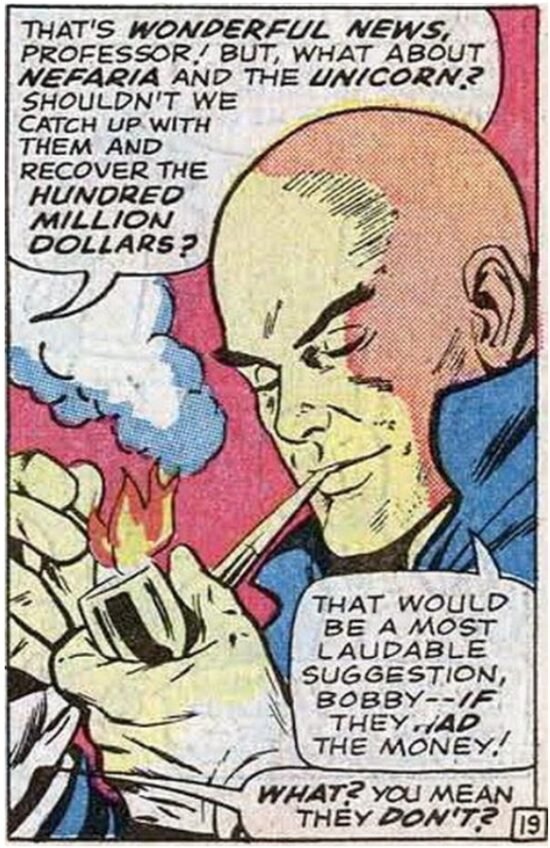

Professor Xavier of Marvel Comics’ Uncanny X-men

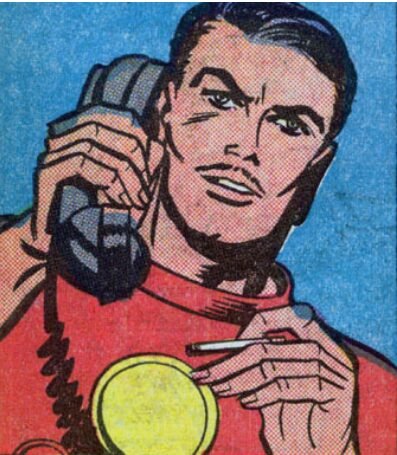

Marvel Comics’ “Iron Man”

Marvel Comics’ spymaster, Nick Fury

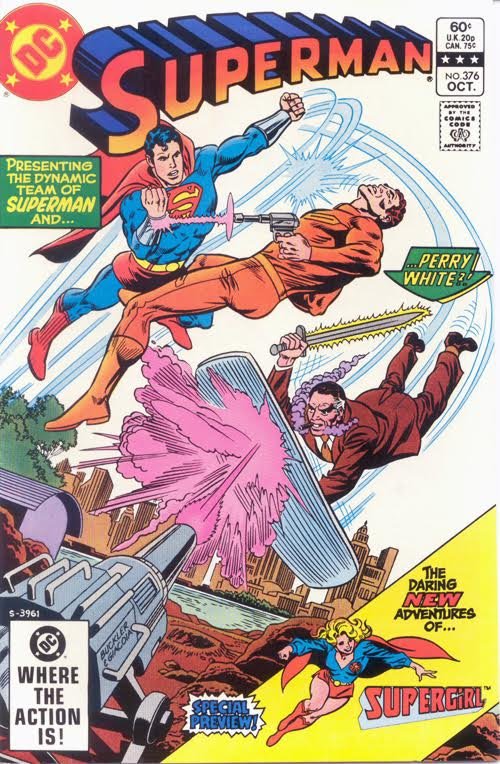

Superman lights up cigars in an odd effort to preserve his secret identity as Clark Kent.

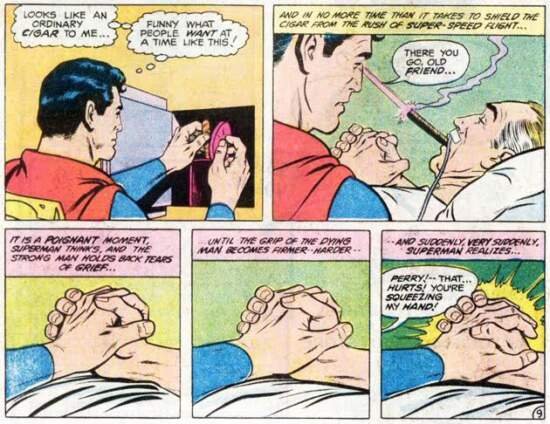

Superman comforts his friend Perry White by lighting his cigar with heat vision: Perry White gains “cigar powers” in Superman #376 (1982).

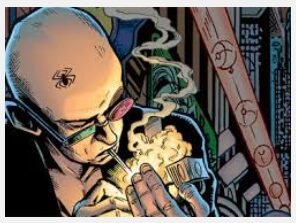

Warren Ellis’ anti-establishment character, Spider Jerusalem, in “Transmetropolitan” (Vertigo Comics)

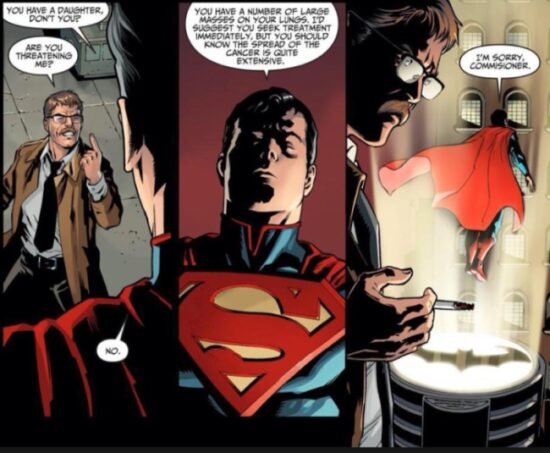

Commissioner Gordon of the Gotham City Police Department is told he has lung cancer by Superman, DC Comics.

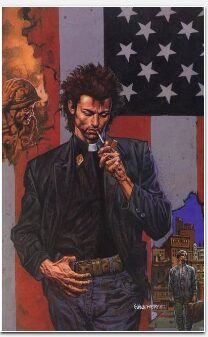

Jesse Custer, the main character of Preacher (Vertigo Comics)

Smoking in Franco-Belgian Comics

The most notable smoker in French comics is (or rather, was) a character called “Lucky Luke”, created by Belgian cartoonist Morris (the nom de plume of Maurice de Bevere, 1923-2001) first appearing in the popular French comic “Spirou” in 1946. “Lucky Luke” was the subject of 87 books, which have been translated into 30 languages and sold more than 300 million copies around the world.

“Lucky Luke” 4, Sous le Ciel de l’Ouest (1952)

In the World Health Forum (Vol 11 1990 footnote “Les cahiers de la bande dessinée” No. 43, 1980, p. 11.) Morris, who had been criticised for allowing the character to smoke, responded that “the cigarette is part of the character’s profile, just like the pipe of Popeye or Maigret”.

The cigarette was discarded in 1983, purportedly to accommodate US comic book distributors – an odd thing, since Marvel Comics as described above allowed its characters to smoke up to 2001.

Re-issued editions of “Lucky Luke” have had the character’s cigarette edited out:

Morris was awarded a commemorative medal from the World Health Organization in 1988 during the organisation’s first No Tobacco Day, as a consequence of Morris replacing Luke’s omnipresent cigarette with a wisp of straw in the story Fingers (1983).

The Franco-Belgian ligne claire title “Blake and Mortimer”, created by Belgian comics writer Edgar P Jacobs, features both title characters smoking pipes. “Blake and Mortimer” started as a back-up feature to “Tintin” (another popular Frannco-Belgian comic) in 1946, and the title has sold 15 million copies. The two characters are Philip Mortimer, a British scientist, and the Welshman Captain Francis Blake of the British Intelligence Service. The original stories, set in the 1950s, deal with detective mysteries but touched upon science fiction and fantasy (including a trip to Atlantis). The title was revived in 1996.

The characters are depicted by their French writers as being quintessentially British, characterised by their slang (“Blimey!” and “old chap”), their mansion on Park Lane in London, and their penchant for pipe-smoking. The most recent editions of their adventures have continued the characters’ enjoyment of pipes.

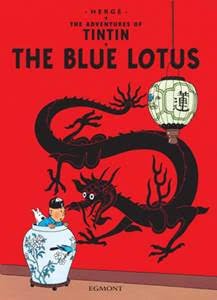

One of the most famous Franco-Belgian comic characters, “Tintin”, created by Belgian writer Hergé, has been the subject of animated adventures: The Telegraph has reported that the depiction of villains smoking in cartoon resulted in the TV network incurring a fine imposed by the Turkish government of USD33000 pounds, as the cartoon breached Turkish laws on the use of tobacco on TV.

Tintin’s ally Haddock is a keen pipe smoker, which, along with the roll-neck sweater featuring a sea anchor and his hat are part of the characterisation of being a sailor.

In the comic book “The Blue Lotus” (1936), Tintin is lying in an opium den in Shanghai pretending to smoke an opium pipe. Such depiction of an underage teen smoking opium would never appear in a contemporary children’s book.