Moon Knight #10

Marvel Comics, March 2017

Writer: Jeff Lemire

American publisher Marvel Comics has engaged in deceptive behaviour with the cover of this issue. In the top right hand corner of the cover appears this red box:

What Marvel Comics actually mean is that this is issue one in respect of the story arc. It is actually issue ten of the series. Marvel Comics’ carpet bombing over the past few years of the American comic book market with first issues of new series indicates that the publisher understands that new readers are reluctant to jump into an ongoing title at mid-point. Some readers may even buy a first issue because of an apprehension that it has increased value as a collectible.

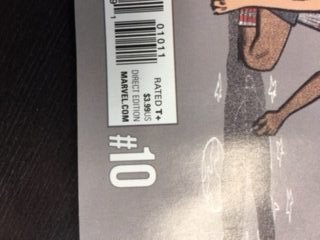

And so this is a new tactic from Marvel Comics: misleading readers into thinking that this tenth issue is actually the first issue of the series. The addition of the actual image number, in grey on white and blended into the publisher’s bar code box located at the base of the cover, does not militate against confusion:

It is a deplorable sales tactic.

In any event, the series is about a masked vigilante named Marc Spector, who uses the moniker “Moon Knight”. The backstory of this character is something we have discussed previously. This present series is heavily invested in the exploration of Spector’s multiple personality disorder. To underscore this, forgoing the white tights and cape, Spector is now dressed very much like the mentally disturbed vigilante called “Rorschach” from the notorious and critically acclaimed title “Watchmen” (1987), written by British scribe Alan Moore. Here is a side-by-side comparison, with Moon Knight on the left, Rorschach on the right:

We assume the re-orientation of the character’s appearance towards that of Rorschach was intentional, a reworking by writer Warren Ellis in 2014 (an aspect of what newspaper “USA Today” quoted as Moon Knight’s “bonkers” phase.

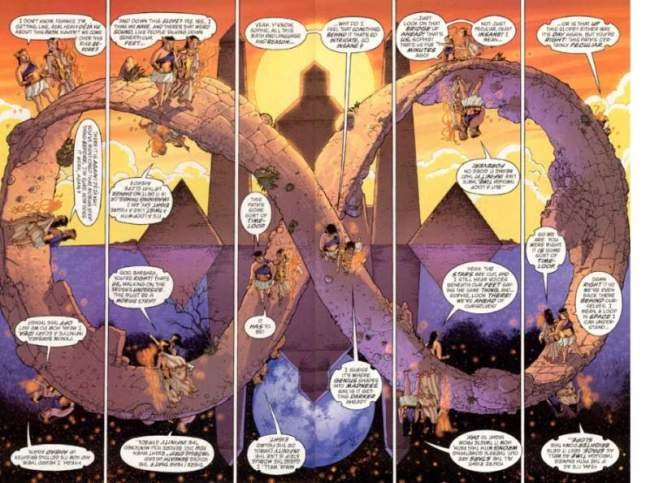

Issue ten has some quite spectacular artwork especially towards the end, when Spector accepts a quest by the Egyptian god Anubis, in exchange for the soul of a character called Crawley (a quick Google search indicates that this character is a homeless man who has been an informant for Moon Knight in previous stories). The issue inverts, requiring the reader to turn the issue upside down as the character passes through strange realms. This is reminiscent of Alan Moore’s work on “Promethea” for America’s Best Comics from 1999-2005: one of the most remarkable images from “Promethea is set out below:

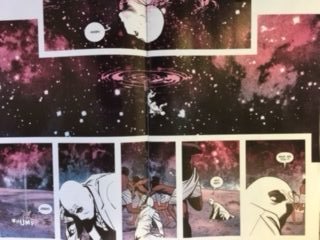

Moon Knight #10’s inversion is not as spectacular, but compelling nonetheless:

If writer Jeff Lemire has taken a leaf out of Alan Moore’s playbook, as Warren Ellis did, then that should disappoint no one.

But the most intriguing aspect of “Moon Knight” #10, by far, is the repeated flashbacks to Marc Spector’s childhood. The story describes how Spector began to share toys with a boy called Steven and later another boy named Jake. Spector’s father cannot perceive these invisible friends and takes Spector to a psychiatrist. These personalities are carried forward in Spector’s life (and appear in earlier “Moon Knight” stories) notwithstanding, as described in this issue, drug therapy and “progressive methods of treatment”. As Spector ascends on his quest into what Anubis calls “the Overvoid”, chilling fragments of doctors’ discussions about Spector’s psychosis appear in dialogue balloons: “Not working. Increase his dosage…” and again, “Not working. Increase the dosage…” A disembodied voice says, contradicting the other word balloons in an adult lie to a small boy, “I’m afraid you’re not ready to go home yet. We have just started making progress”. And then, the most sinister fragment, “Might need to try more aggressive methods” accompanied by a grainy image of the pre-teen Spector undergoing shock therapy.

The picture painted by Mr Lemire’s dialogue in these two pages is of a young boy, trapped in a mental ward and way from home, a guinea pig for psychiatrists. Given how harmless Spector is depicted as a boy, playing with action figures, “Moon Knight” #10 is an unpleasant and sad story, and perhaps the treatment of the disease, rather than the disease itself, explains why the adult Spector is so badly misadjusted. The dialogue is sparse and precise in what it sets out to achieve, and in that regard represents fine writing.

But further, is the ascent into “the Overvoid” in any sense real? Is the journey into another dimension just in Spector’s head, given the accompanying images and text out of the memories of Spector’s tattered past? Or is Spector’s madness a necessary vehicle for the journey (Anubis, after all, calls Spector “traveller”)? Reality and psychosis interfold. A disturbing, well-executed story.