Hostage

Penguin House / Jonathan Cape, 2017

Writer: Guy Delisle. Translator: Helge Dascher

This is our latest review of independently published comic books, following on from Free Comic book Day on 5 May 2017. Links to our previous reviews are here, here and here. This review is only technically an independent publication, in the sense that it is published by global giant Penguin, a business not usually known for graphic novels.

One of the gifts of the medium of comic books is to project an acute sense of time’s passage through use of panel repetition. In Alan Moore’s “Watchmen” (DC Comics, 1986), the repetition of a twelve panel grid by artist Dave Gibbons containing almost identical background scenes underpinned a procession of activity over a short period of time. Each panel was a symbolic ticking of the doomsday clock, an iconic element of that remarkable comic book.

This English translation of the French ligne claire comic “Hostage” is an extended interview by writer Guy Delisle of Medicins Sans Frontieres worker Christophe Andre. Mr Andre is based in Nazran, in Ingushetia, a Russian republic bordering Chechnya. The lawlessness and troubles of Chechnya are well documented. “Hostage” captures that: the men all carry AK-47 machine guns; there is no murmur on the street at the appearance of a Western hostage as he exits a car with a pistol held at his stomach; Mr Andre’s captors which a soccer game on television one night and violent propaganda videos the next. It is a scary place.

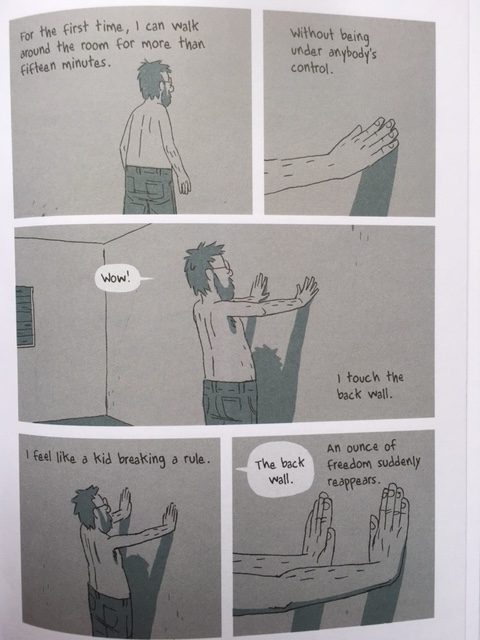

Mr Andre is repeatedly transferred from one location to another. Each are more dire than the last. Each are harrowing in their absence of features. Almost all consist of a stale room, a bare light globe, an old mattress, and a boarded up window. Another room has a radiator to which Mr Andre is handcuffed. Finally, Mr Andre finds himself in a storage room filled with clutter, where he is handcuffed to a ring cemented into the floor. Each shift in location represents the possibility of progress in negotiations for Mr Andre’s release, and Mr Andre’s spirits lift. He then becomes depressed as he realises that his release is not imminent.

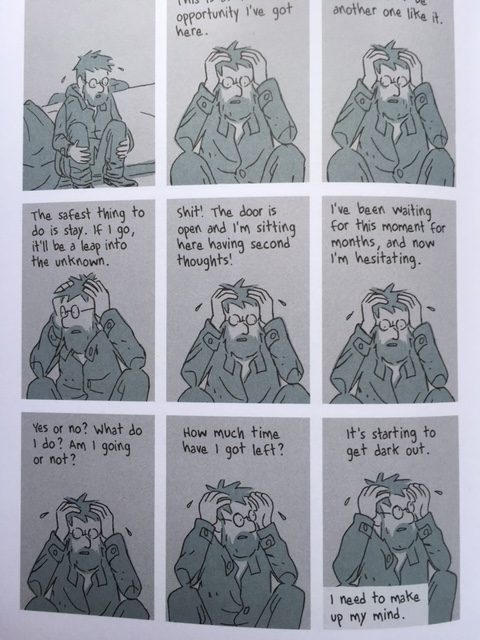

Mr Andre’s torment is described in the sequential panels. Mr Andre is able to discern night and day, but has little understanding of time’s passage otherwise. Each panel is a tick of the clock. But that tick-tock could represent a second, or hours. The art is deliberately static. Mr Andre’s existence becomes hazy. He often falls asleep during the day, with little else to do. Time’s passage otherwise is only certain from the delivery of meals twice a day, and the slow onset of the gloom of night. Small events – the splash of his watery broth onto the floor when delivered by his captors, a brief glimpse of a little boy from next door who has been inadvertently terrorising Mr Andre with the intermittent bouncing of a basketball against the wall – are momentous events in Mr Andre’s limited existence as a hostage.

The art is not laden with the intricate message-laden detail of “Watchmen” (or indeed writer Grant Morrison’s homage to “Watchmen”, called “Pax Americana”, which we have previously reviewed). Instead it is studiously repetitive with perspectives from high angles in the corners of Mr Andre’s prisons. The reader looks down on the forlorn man, isolated and in chains. A limited colour palette of dark hues completed the mood.

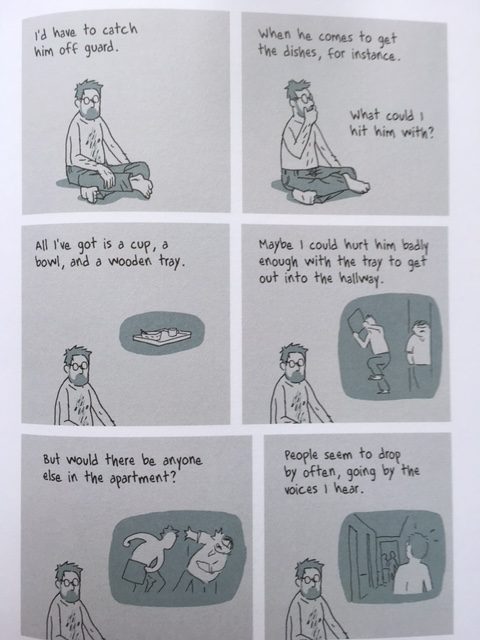

Although Mr Delisle is the writer and artist of this work, the story and the voice is that of Mr Andre. He is clearly a conservative accountant, the sort of person who in finding himself in a dire predicament repeatedly does not allow himself to panic. He knows there is a process in the negotiations for his release, and he knows he has to wait until that process is concluded. He initially thinks he was abducted for the purpose of access to MSF’s office safe, and he is surprised when things become unpredictable. He is parsimoniously horrified when he learns that his captors want $1 million for his release. He is mildly pleased that, upon seeing the date on a newspaper, that he has successfully kept track of the days across the months. Perhaps most people would not, but Mr Andre is an accountant: process-driven, frugal, precise, and the reader is left with the impression that this professionally-honed patience, this rationalisation of the problem and the inevitability of a solution, is what saves him from occasional lapses into despair and anger.

Mr Andre sometimes dreams of violence against his captors, and if escape. One such effort at prying at his handcuffs caused the manacle to clamp hard into his wrist, and he spends a painful night massaging blood flow into his strickened hand. Once, he slips down a corridor when he thinks he is alone, only to be intercepted. He is cuffed around the head and deprived of food for the evening. Months pass. As the weather cools, he is given a blanket. One day his captors forget to cuff him after he is returned from the toilet, and he feigns sleep under the blanket, his wrist hidden. Mr Andre agonises over escape, and eventually decided to do it. Kindly strangers facilitate his release.

This is a riveting comic book, a study of captivity and mental survival.