Our publication has a category devoted to “superheroes”. It is a genre to which we have paid disproportionate attention, primarily because it is in English (the language of most of our contributors) and because of the sheer volume of superhero-genre material generated primarily by American publishers.

But what does the word “superhero” actually denote? The words “super hero” was first used in 1917, when it was used to describe a “public figure of great accomplishments”

In so far as use of the word “superhero” in the course of commerce is concerned, however, there is a severe limitation. The word “superhero” is jointly owned in many parts of the world by two US publishers, DC Comics and Marvel Characters Inc, an affiliate of Marvel Comics. The road to joint ownership of the word “SUPERHERO” in the United States is well-explained in this link.

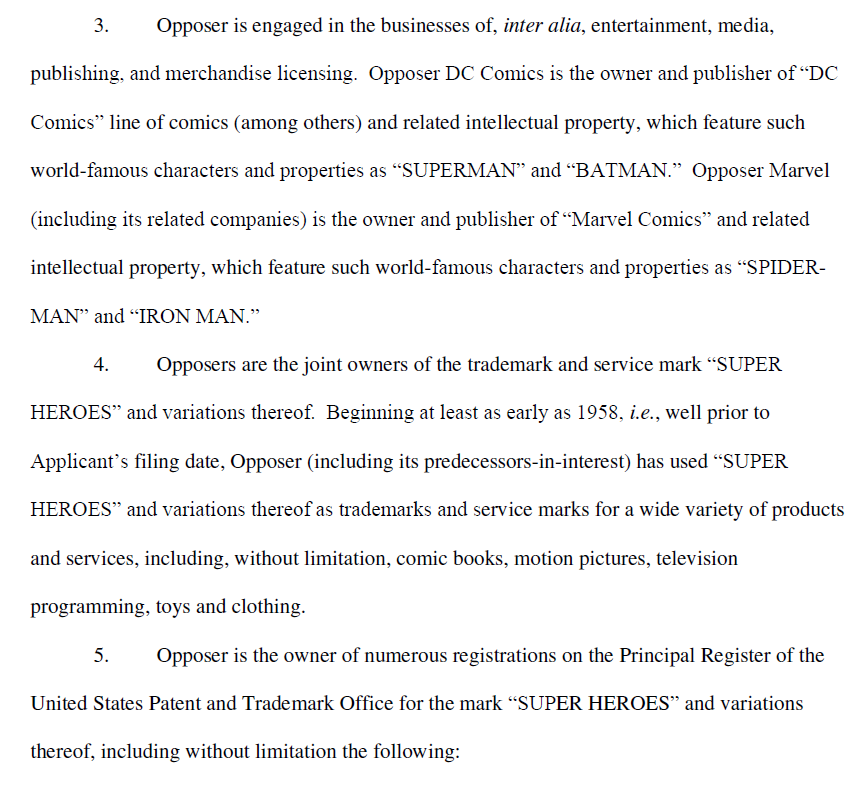

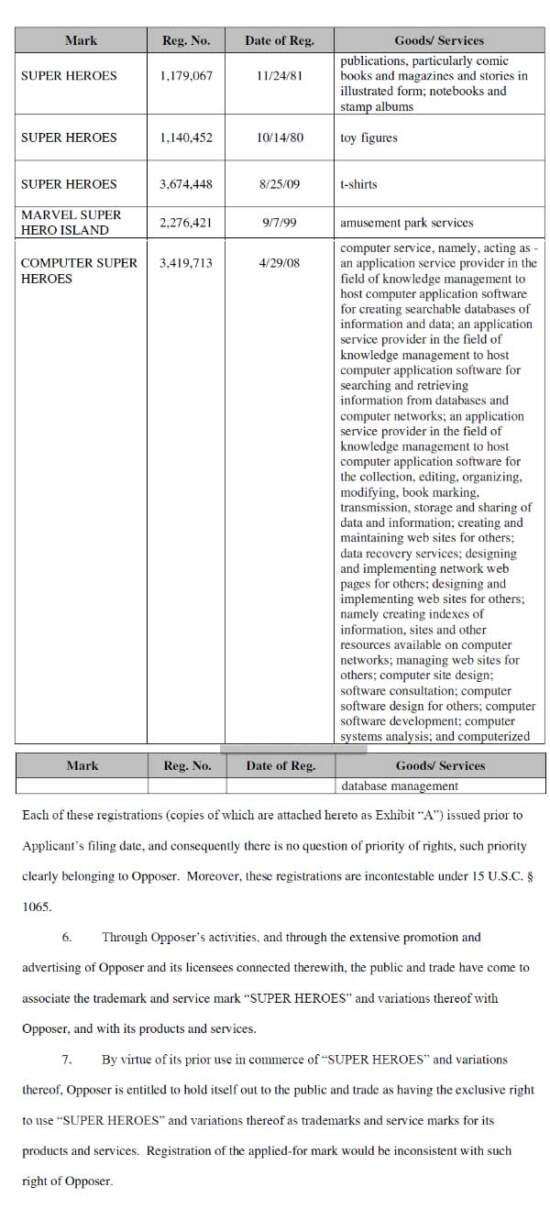

But perhaps a more concise explanation comes from both DC Comics and Marvel themselves. The following paragraphs come from a United States trade mark notice of opposition filed by DC Comics and Marvel in May 2015:

It appears that at some stage, most likely in 1979 if this article is correct, that instead of competing in respect of the use of the name, the two publishers decided to join forces in respect of the global commercial exploitation of the word “SUPERHERO”.

The formal agreement between DC Comics and Marvel governing these joint ownership rights does not appear to be publicly available.

This begs the question: how did ownership of the word “superhero” come to be? How did two publishers come to own a word which describes a very popular and very long-lasting genre of comic book publications?

It is not enough for a business to simply say that they own a brand. Obtaining formal ownership rights in a brand is done by way of a trade mark registration.

In essence, a trade mark registration is a statutory monopoly right to a brand, limited to specific types of goods and services.

So, to use an example, international sporting goods company Nike cannot claim a statutory monopoly right for the word “NIKE” in respect of, say, chemicals for use in energy production. The scope of the monopoly in a trade mark does not extend so far as to prevent anyone engaged in business from using the brand in respect of anything at all (with rare exceptions such as “COCA COLA” and other internationally famous, coined brands).

DC and Marvel’s joint strategy, in place since as early as 1977, is to file trade mark applications, in order to obtain a perpetual monopoly in the word “SUPERHERO”. There is a formal process to this. A trade mark application is filed with a trade mark registry in a country where the applicant (or in this case, applicants) desires the monopoly right. The application then undergoes a period of examination, whereby it is assessed for, put very simply and with variations from country to country, the ability of the brand to function as a properly registered trade mark. Questions the examiners ask of themselves and of the applicant during that process include whether any third party would, in a bona fide way (that is, with an absence of bad faith), wish to use the trade mark to describe the goods and services.

Once that hurdle is overcome, and importantly in respect of this article, the trade mark application can be opposed by a third party. If the mark is not opposed, or successfully navigates the opposition process, a certificate of registration is issued by the registry. That certificate is typically capable of renewal every ten years, thus creating a perpetual monopoly in the brand. Thus a brand, through the process of a trade mark application, becomes an enforceable trade mark registration.

Marvel and DC have been through this process repeatedly in many countries. The two publishers have, remarkably, put forward the proposition, implicitly or otherwise, that no other party would wish, in a bona fide way, to use the brand “SUPERHERO”. And the two publishers have repeatedly been successful in that.

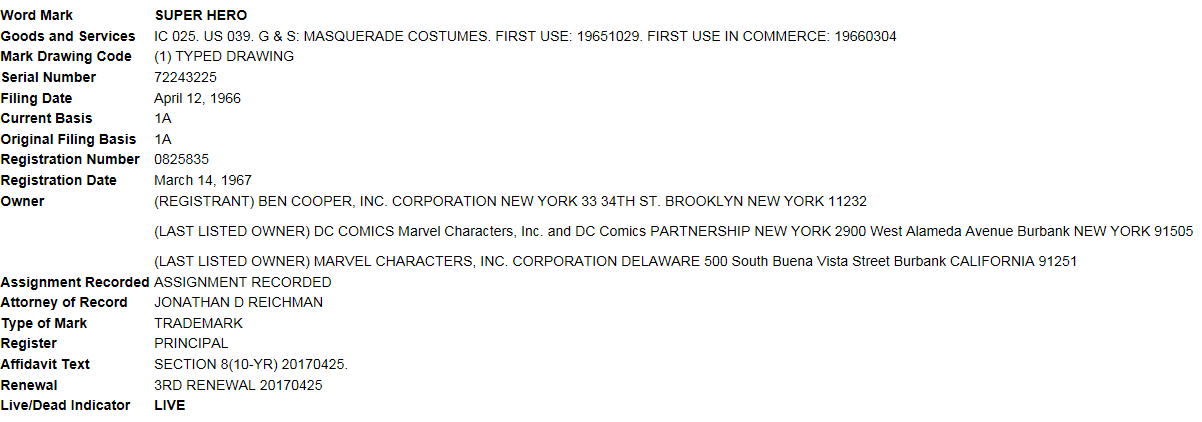

The oldest of these trade mark registrations in the United States dates back to 1966. It was registered by Ben Cooper Inc and subsequently assigned to DC Comics and Marvel following a dispute which ended in 1977. Here is an extract from the United States Patent and Trademark Office’s database:

Our article considers how DC Comics and Marvel have systemically prevented people from using the word “superhero” in a general trade context, well-beyond the scope of comic books.

(Within this article, we abbreviate Marvel Characters Inc to “Marvel”. We also note, at the forefront, that although this academic article considers legal issues and even case law, it does not under any circumstances constitute legal advice.)

“Business Zero to Superhero”

We begin in 2016 with an effort by Mr Graham Jules to register a trade mark incorporating the word “superhero” in the United Kingdom in respect of a business-orientated publication.

In the United Kingdom, DC Comics and Marvel are the joint proprietors of the mark SUPER HEROES (“the registration”). They jointly applied for the registration on 12 December 1979. The registration covers the following goods in Class 16:

Paper table napkins, invitation cards, stationery, pens, pencils included in Class 16, stamps (not being tools) stamp albums, photograph albums, notebooks, scrapbooks, colouring books.

In April 2016, DC Comics and Marvel’s lawyers issued a cease-and-desist letter to British author Graham Jules, who had written a business start-up book for entrepreneurs called “Business Zero to Superhero”. It sounds very much like the sort of book that bored business passengers might buy in an airport news agency. In radio interviews on the BBC and The Mail on Sunday, Mr Jules said, “I was very shocked, I’m a new author and small business and I’m now in the position of fighting or scrapping the entire book”. During the process of the trade mark application, which we have described above, DC Comics and Marvel opposed Mr Jules’ trade mark for the title of the business book.

In 2016, Mr Jules’ company, Start Up Pop Up Ltd counterattacked. Mr Jules applied to the UK Trade Mark Registry for orders that DC Comics and Marvel Entertainment’s trade mark registration for “SUPERHERO” to be declared invalid. The grounds to revoke registration were:

The registration offends under Section 3(1)(a) of the UK Trade Marks Act 1994 (“the Act”) because the term SUPER HEROES is a common generic term used by the media, in entertainment and in books and because the term is not unique to the proprietor.

The registration offends under Section 3(1)(b) because the term SUPER HEROES is not distinctive enough. It draws analogy to Marvel’s registration of the mark ZOMBIES in the mid-1970s following the success of its publication “Tale of the Zombies”. The applicant claims that because of the overwhelming popularity of the archetype, Marvel realised that it was impossible to enforce its rights in this mark and it went on to register “Marvel Zombies” together with the disclaimer “No claim is made to the exclusive right to use zombie”;

The registration offends under Section 3(1)(c) because the mark is contrary to the “free to use” doctrine established by the EU courts and it claims that the term SUPER HERO is descriptive of a character within fiction that carries superpowers; and

The registration offends under Section 3(1)(d) of the Act because the term SUPER HERO is used in a customary way in entertainment and fiction.

Mr Jules represented himself. Mr Jules was a law student but not a specialist trade mark lawyer. He failed to provide sufficient evidence indicating what the state of the mind of the typical consumer as at 1979 was in respect of their understanding of the word “SUPERHERO”. Under UK trade mark law, this is the test for invalidation – was it a generic term in 1979, as understood by consumers in 1979? The hearing officer repeatedly noted this, for example:

“The onus is upon [Mr Jules] to demonstrate that, in 1979, the average consumer would perceive the term SUPERHEROES when used in respect of the goods for which it is registered, as indicating a characteristic of those goods rather than trade origin. As I have already commented, there is no evidence before me to illustrate this. There is nothing to suggest that, at that time, the average consumer, upon encountering the contested mark being used in respect of such goods, would perceive it as anything other than an indicator of trade origin.”

However, newspaper reports indicate that after the issue of the judgment on Mr Jules’ invalidation action and a few days’ before the hearing on the opposition to Mr Jules’ trade mark application, DC Comics and Marvel gave up on their claims to Mr Jules, citing “commercial reasons.”

Mr Jules’ book on start-up tips for businesses was entirely unrelated to comic books, nor to the adventures of caped and masked heroes which are the staple of DC Comics’ and Marvel’s respective publications. It is the breadth of the trade mark registration that gave DC Comics and Marvel the ability to send the cease and desist letter to Mr Jules. The scope of protection of DC Comics and Marvel’s UK trade mark registration, which covers “Paper table napkins, invitation cards, stationery, pens, pencils included in Class 16, stamps (not being tools) stamp albums, photograph albums, notebooks, scrapbooks, colouring books” can arguably at law include other paper products, such as books, irrespective of the content of those books. This would have been a remarkable extension of the statutory monopoly right.

As this legal blog notes:

“This case has the characteristics of a legal department of a large company gone awry. In Graham’s case, one could hardly point to a likelihood of commercial confusion. No one in their right mind would confuse Jules’ everyman “superhero-small-time business owner” with Batman or The Incredible Hulk.”

But the substance of the dispute, in this instance pitting DC Comics and Marvel against Mr Jules, is not a one-off aberration.

“A World Without Superheroes”

In 2010, Mr Ray Felix, a comic book creator in New York, self-published a comic book called “A World Without Superheroes”. Mr Felix maintains that the comic sold less than 1000 copies. In August 2010, Mr Felix applied for a trade mark for the title. An extract from the US Patent and Trade Mark Office’s trade mark register appears below:

Mr Felix in press coverage affirmed his right to register the mark. “At first they seemed to be friendly, but once I brought into question their limitations of the word Super Hero and presented my right to use my published mark, their lawyer began to grunt and lose patience in our conversations and then began making sharp remarks.”

According to United States Patent and Trade Mark Office records, DC Comics and Marvel applied for default judgment against Mr Felix, and were successful – the order is set out in this link Mr Felix then fought that order. But on 26 March 2012 the parties moved for a suspension of the opposition, on the basis that settlement negotiations were ongoing. These negotiations were obviously unsuccessful, because on 11 December 2012 Mr Felix filed a statement setting out, in essence, his defence to DC Comics’ and Marvel’s claims. Within this document, Mr Felix takes aim at DC Comics and Marvel’s conduct:

The matter crawled along and trial dates for the opposition were reset. On 25 May 2014, DC Comics and Marvel applied to suspend the opposition again, on the basis that settlement negotiations had resumed. Mr Felix withdrew the application on 11 June 2014.

DC Comics and Marvel’s lawyer, Jonathan Reichman is reported as saying,

“We are not trying to remove a word from the English language… We are just doing what we have done for decades – protect a trademarked term. And we always try to resolve matters amicably instead of going for a court hearing, which saves everyone a lot of time and money.”

Mr Reichman is doing his job as a very competent trade mark lawyer on the instructions of his clients. Mr Reichman’s statement to the press must have been authorised by his clients. That statement endeavours to describe Marvel and DC Comics as fair players, and not corporate entities trying to carve out a term from the English vernacular.

The Australian Experience

Australian trade mark records are very accessible and reasonably detailed. Below is what we have been able to extract from those records.

First, in November 1996, an Australian company called Hero Marketing Pty Ltd applied for this trade mark (721761) in respect of “Laundry liquid; dishwashing liquid; mould and mildew remover; bath and shower cleaner; and soap scum remover”

The trade mark was opposed by DC Comics and Marvel on 14 November 1997. The opposition was dismissed on 3 December 1998, but by 14 May 1999 DC Comics and Marvel mounted a second attack, and successfully cancelled the trade mark.

Neither DC Comics nor Marvel are involved in the sale of “Laundry liquid; dishwashing liquid; mould and mildew remover; bath and shower cleaner; and soap scum remover”.

Second, on 27 April 2004 an Australian company called Intrinsic Alliance Pty Ltd applied for this trade mark (999384) in respect of “Outdoor adventure activities, educational programs, recreational activities, fitness activities”:

By 26 November 2004, the application was opposed by DC Comics and Marvel Characters Inc, and the trade mark application was subsequently withdrawn.

Neither DC Comics nor Marvel are involved in the provision of “Outdoor adventure activities, educational programs, recreational activities, fitness activities”.

Third, on 2 June 2005, a large Australian supermarket chain called Metcash Trading Limited applied for a trade mark, “SUPERHERO SPECIALS”, filed in respect of:

Wholesaling, distribution and retail services in relation to supermarkets and similar stores; retail, wholesale and distribution of equipment and supplies for the operation of retail outlets, including convenience stores and supermarkets, including checkout bags, paper bags, produce bags, miscellaneous bags, cash register rolls and ribbons, carton cutters and blades, packaging and wrapping materials for fresh food including prepack trays, foam trays, soap pads, containers, plates, labels and markers, cutting boards, cleaning preparations and apparatus including wall mounted cleaning apparatus, floor cleaning preparations, absorbent powders, industrial cleaning preparations, paper towels and wipes, clothing, footwear and headgear including caps and gloves for use in food preparation and handling and uniforms, mobile and fixed telephones, computers, electronic funds transfer and automatic teller machines terminals; retail and wholesale and distribution services including retail grocery store services; business management and administration of retail outlets, including convenience store and supermarkets, business information services, negotiation of electricity supply, negotiation of the purchase and maintenance of fleets of vehicles for commercial use, provision of business information, marketing research and studies; retail development and store equipment services; advertising services

By 29 December 2005, DC Comics and Marvel had opposed the application, and it was withdrawn.

Neither DC Comics nor Marvel are involved in the goods and services offered by a supermarket chain.

Fourth, on 14 July 2006, a company called The Lucky Drink Company Pty Ltd filed two applications, one for the trade mark “SUPERHERO BEER”, in respect of “beer”, and one for the trade mark “SUPERHERO COLA” in respect of “aerated drinks (non-alcoholic)”. By 16 February 2007, DC Comics and Marvel had opposed the application, and it was subsequently withdrawn. Another trade mark filed by this company, for “Superhero” in respect of “Beers; mineral and aerated waters and other non-alcoholic drinks; fruit drinks and fruit juices”, was subsequently withdrawn after being opposed by DC Comics and on 1 May 2007.

Again, neither DC Comics nor Marvel are involved in the sale of beer, mineral water, or cola.

Fifth, a trade mark for “Superhero Sam” was filed on 6 July 2007 in respect of “charitable fundraising”. The trade mark was opposed by DC Comics on 8 February 2008. On 18 February 2009, the trade mark was assigned from the applicant to DC Comics and Marvel. It would appear that this unknown charity was compelled by the opposition process to assign to DC Comics and Marvel the rights to this brand.

Neither DC Comics nor Marvel are involved in the provision of charitable services.

Sixth, on 23 June 2009 a company called HP Assets Holdings Pty Ltd filed an application for “SUPERHERO” in respect of “Chilled pizzas; frozen pizzas; pizza; pizza bases; pizza crusts; pizza dough; pizza flour; pizza mixes; pizza pies; pizza products; pizza sauces; pizza spices; pizzas; pre-baked pizzas crusts; preparations for making pizza bases; prepared meals in the form of pizzas; prepared pizza meals; uncooked pizzas; foodstuffs made from farinaceous products; garlic bread; prepared meals in the form of pizzas”. By 22 January 2010 DC Comics had opposed the trade mark, and it was withdrawn on 11 March 2010.

Neither DC Comics nor Marvel are involved in the pizza industry.

Seventh, on 10 January 2015 a company called Tech Girls Movement Pty Ltd applied for the trade mark “TECH GIRLS ARE SUPERHEROES” in respect of:

Education software; Electronic publications (downloadable); Talking books, Books; Educational materials in printed form; Printed matter; Printed publications: Apparel (clothing, footwear, headgear): Career advisory services (other than education and training advice); Event management services (organization of exhibitions or trade fairs for commercial or advertising purposes); Marketing; Writing advertising copy: Provision and funding of scholarships; Financial sponsorship of education, training, entertainment, sporting or cultural activities: Advisory services relating to publishing; Book publishing; Provision of information relating to publishing; Publishing by electronic means; Publishing services; Book lending; Copy writing; Preparation of texts for publication; Publication of electronic books and journals online; Event management services (organisation of educational, entertainment, sporting or cultural events); Organisation of exhibitions for cultural or educational purposes; Providing information, including online, about education, training, entertainment, sporting and cultural activities; Career information and advisory services (educational and training advice); Charitable services, namely education and training; Design of educational courses, examinations and qualifications; Technological education services; Training: Design of printed matter; Information services relating to information technology; Design of promotional matter; Graphic design services; Layout design of books and magazines; Web site design

This trade mark application was opposed by DC Comics and Marvel on 10 September 2014. The matter is ongoing, and is scheduled for a hearing for determination in 2017. Neither DC Comics nor Marvel are involved in educating girls in respect of technology.

Eighth, on 23 June 2016, a company called Will & Caro Pty Ltd applied for the trade mark “Superhero Pills” in respect of:

Articles for use in writing; paper, cardboard; boxes of cardboard or paper; placards of paper or cardboard; paper; bookbinding material; printed matter; stationery; photographs; plastic materials for packaging, not included in other classes; plastic materials for wrapping; office requisites in this class; office requisites for commercial use; office requisites for domestic use; office requisites, except furniture; adhesives for stationery purposes; artists’ materials; artists’ papers; paintbrushes; announcement cards (stationery); copying paper (stationery); covers (stationery); document files (stationery); envelopes (stationery); index cards (stationery); paper sheets (stationery); school supplies (stationery); office supplies (stationery); stencils (stationery); stickers (stationery); wrappers (stationery); writing cases (stationery); photograph stands; pads (writing); pads (stationery); book wrappings; gift wrap; wrapping paper; books; note books; photo books; picture books; pocket books (stationery); printed books; writing implements writing pads; greeting cards; musical greeting cards; instructional material; teaching materials (except apparatus): Apparel (clothing, footwear, headgear); aprons (clothing); clothing; footwear; headgear for wear; sleepwear; underwear; slippers; shoes: Retailing of goods (by any means); advertising and promotion; business management; business administration; office functions; wholesaling; distribution; retailing; wholesale of household products, gifts and fashion accessories; distribution of household products, gifts and fashion accessories; retail sale of household products, gifts and fashion accessories; retail and wholesale services including mail order and online retail and wholesale services, all being in relation to paper, cardboard and goods made of these materials, printed matter, stationery, office requisites, photographs, plastic materials for packaging

On 15 January 2017 this trade mark was opposed by DC Comics and Marvel. Will & Caro Pty Ltd filed a notice of intention to defend on 1 June 2017. The matter is ongoing.

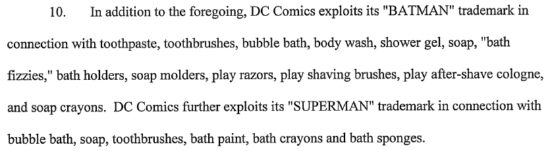

Brand Extension

To be fair, both DC Comics and Marvel generate considerable revenue through the license of their intellectual property assets to manufacturers and retailers. This is why items such as Batman lunchboxes or Spider-Man bicycles can be purchased by consumers. To look at the sixth example of the Australian experience listed above, it is very feasible that, by way of example, that DC Comics might license its “WONDER WOMAN” property to a pizza chain particularly given the release of the recent “Wonder Woman” motion picture.

Indeed, DC Comics and Marvel explain this business of revenue generation by licensing its character concepts for merchandising in a document filed in October 2008, in the context of a US trade mark dispute in which the two companies opposed a trade mark application for “SUPERHERO” filed by Michael Silver in respect of, amongst other things, sun screen:

But neither DC Comics nor Marvel, as best as we can determine, license the word “SUPERHERO” or any variant to anyone. Nowhere within any of the legal documents filed by DC Comics or Marvel in the trade mark oppositions we set out above or below can we find reference to the license of the word “SUPERHERO” to any person at all. Instead there is only repeated reference to the entitlement to license.

Even if Marvel and DC Comics did do this, looking at the first example in the list of the Australian experience, it would intuitively be an odd thing to license the word “SUPERHERO” to a company involved in the sale of soap scum remover.

And, on the face of it and without any explanation as to what occurred, it is at best sad that DC Comics and Marvel decided to attack a charity wanting to register the brand “Superhero Sam”.

The US Experience

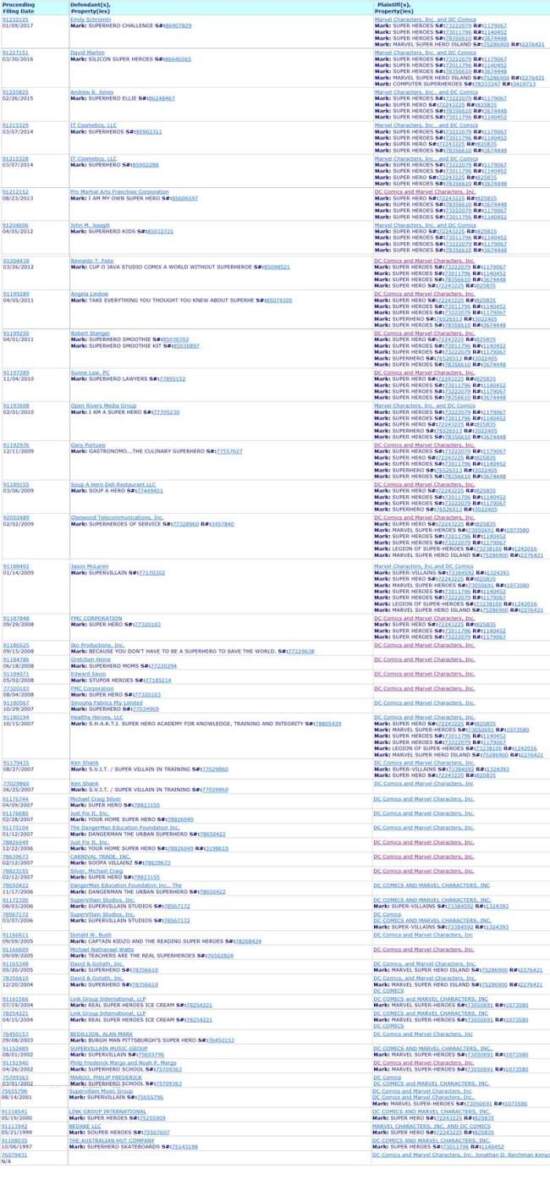

The United States Patent and Trade Mark Office maintains extremely detailed online records of oppositions to trade mark applications. Here is the USPTO’s list of oppositions filed by Marvel and DC Comics to trade mark applications in the United States, in reverse chronological order, dating back to 1997:

Included in that list is Mr Felix’s doomed trade mark application. Another application, which curiously does not appear on the list, is the trade mark application for “SUPERHERO BATTLEGROUND”, apparently filed in February 2015 and which according to this site was also opposed by DC Comics and Marvel.

This list, in our view, demonstrates a systemic campaign within the United States to prevent various third parties from securing a statutory monopoly right in any brand incorporating the word “superhero” in respect of many types of goods and services.

Other notable disputes

Various other disputes have been either commented upon on the internet or available to access in collections of legal decisions. Here are some of them:

First, in March 2006 US comic book publisher GeekPunk is announcing that its flagship comic book title featuring off-duty superheroes relaxing at a bar would be re-badged as “Hero Happy Hour”. According to creator Dan Taylor, “The decision to change the title was brought upon by the fact that we received a letter from the trademark counsel to ‘the two big comic book companies’ claiming that they are the joint owners of the trademark ‘SUPER HEROES’ and variations thereof.”

Second, in 2011, in a dispute in New Zealand called “Superloans Limited v DC Comics, a general partnership comprised of Warner Communications, Inc and E.C. Publications” DC Comics’ efforts to prevent trade mark registration of this character (called “Buck”) were denied:

The decision maker said in his reasons:

“I consider that the generic elements of BUCK: (1) being a superhero ; (2) wearing a fitting body suit with a logo on the chest; (3) wearing a cape; (4) having muscular tone denoting strength, speed, and fitness; and (5) the ability to fly are not unusual in the context of superheroes . It is the way that those elements have been expressed in the BUCK character, which I consider is significant. On balance, I consider that the opposed mark is an independent creation, which, at best, may have been generally influenced by superhero characters, but I find that it is not established that the opposed mark is the product of copying any particular superhero character, in particular, the SUPERMAN character.”

Interestingly, the hearing officer uses the word “superhero” in a generic sense within his reasons for decision.

Third, in 2014, an application seeking to revoke the United Kingdom registration of the trade mark “FUEL THE SUPERHERO INSIDE” on the grounds that it has not been put to genuine use was filed by DC Comics (and Marvel. The trade mark FUEL THE SUPERHERO INSIDE was entered into the United Kingdom trade mark register on 16 September 2005 under no 2381932 and stands in the name of Bio-Synergy Ltd. It was registered in respect of the following goods: Vitamin supplements; Milk based drinks for children; Fruit based drinks for children. This application failed when Bio-Synergy Ltd filed evidence of genuine use.

Conclusion

To be clear, trade mark registrations only affect “trade”. There is no impediment imposed by DC and Marvel’s trade marks upon people referring a “superhero”, nor referring to the “superhero” genre in, for example, our and others’ critiques. Generally speaking, trade marks are only concerned with business activities.

Mr Reichman said, on behalf of his clients, “We are not trying to remove a word from the English language… We are just doing what we have done for decades – protect a trademarked term”. But the assertion does not ring true. In multiple jurisdictions across the world, DC Comics and Marvel oppose trade mark applications which cover goods and services which are not even vaguely associated with comic books, comic book characters, or items which might be the subject of revenue-generating licensing regimes. Further, DC and Marvel appear never to actually license the word “SUPERHERO” in any event, so the prospect of injury to DC Comics’ and Marvel’s respective businesses caused by, say, an Australian trade mark application made by a company providing soap scum removers, or a UK trade mark application made by a man who has written a book about business tips for start-up companies, seems incredibly remote.

What DC Comics and Marvel have done, and successfully, notwithstanding their assertions otherwise, is to monopolise the word “superhero” – a part of the English language – in so far as it is used to describe any aspect of business activity. Trade mark registrations were not designed to do this.

One possibility is that DC Comics and Marvel are building a portfolio of evidence. If there was ever a serious challenge to the two publishers’ ownership rights, then DC Comics and Marvel would be able to clearly demonstrate that they had been diligent in policing their brand.

That challenge would most likely manifest as an attack on the word “SUPERHERO” on the basis of its genericisation. The concept that a registered trade mark can become generic is well-known. Examples of brands which have either become generic or are generic include “ROLLERBLADE” (now a generic word for inline skates), “VELCRO” (for the fastening mechanism), “ASPIRIN” (for the pharmaceutical pain killer), “LINOLEUM” (for the floor covering), and “SELLOTAPE” (for the adhesive tape).

Adopting a descriptive word comes with risks, and quite properly so. The situation is somewhat analogous to the remarks of an English judge, Lord Davey, in a 1899 case called Cellular Clothing Co Ltd v Maxton & Murray:

“… where a man produces or invents … a new article and attaches a descriptive name to it – a name which, as the article has not been produced before, has, of course, not been used in connection with the article – and secures for himself either the legal monopoly or a monopoly in fact of the sale of that article for a certain time, the evidence of persons who come forward and say that the name in question suggests to their minds and is associated by them with the plaintiff’s goods alone is of a very slender character…”

More recently in 1996, and in more modern language, another English judge, Justice Jacobs, explained in a case called British Sugar plc v James Robertson & Sons Ltd:

“There is an unspoken and illogical assumption that “use equals distinctiveness”. The illogicality can be seen from an example; no matter how much use a manufacturer made of the word “Soap” as an unsupported trade mark for soap the word would not be distinctive of his goods.”

Irrespective of what consumers believed in respect of registration of the word “SUPERHERO” at the time of the application in whichever country, the brand is now almost certainly generic for a:

a. genre of literature describing the adventures of people , often in masks and costumes, sometimes with superhuman powers, often fighting each other;

b. type of very positive accolade.

But even if we are wrong in that view, minor orthographical changes may make major changes to the identity of a trade mark. This is especially so when the registered trade mark is weak trade mark material, such as “SUPERHERO”. In many jurisdictions, changes to words which are inherently generic are absolute, and do not necessarily confer rights in the words from which the registered trade mark is derived. As discussed in an Australian decision from 2006 called Deckers Outdoor Corporation v B&B McDougal, debating, in essence, the generic nature in Australia of the words “UGG BOOTS”:

“…For example, a change from the word QUICK to the trade mark QWICK might, on the establishment of the trade mark’s capacity to in fact distinguish in respect of ‘courier services’, allow registration. However, such registration would not in itself confer rights in the word QUICK and evidence of use of the sign QUICK by an opponent may thus not establish use of the registered trade mark QWICK. Minor orthographical variations, such as elision, may make major differences to how words are perceived and recognized. For example, the different expressions WEE KNIGHTS and WEEK NIGHTS contain the same letters in the same order and (via elision of the space in the respective expressions) may be similarly rendered WEEKNIGHTS and yet the original expressions have quite divergent meanings. I can only conclude, since the trade mark UGH-BOOTS is registered, that it must (since, despite whatever reservations I might have about its capacity to distinguish, it is registered) be viewed in a similar way and that the hyphen is absolutely essential to its identity as a trade mark. The registration should not therefore be viewed as conferring rights in the generic term, or terms, from which it is derived. The uses of these generic terms by the opponent are not, therefore, uses of its registered trade mark.”

If the reasoning in that decision is correct, any, even minor, variations to the trade mark “SUPERHERO” which are contained in trade mark applications must be registerable. “SOUP A HERO”, on that rationale, would certainly be registerable as a trademark. And certainly “Business Zero to Superhero” would be registerable as a trade mark.

All of the matters set out in our lists above were settled by DC Comics and Marvel before any hearing, suggesting that the two publishers know that an adverse decision against their ownership rights in “SUPERHERO” might have a domino effect in other jurisdictions. Whether any well-heeled competitor decides to challenge DC Comics and Marvel in a court in respect of their statutory monopoly rights in the word “SUPERHERO” remains to be seen.