“Lost in the Funhouse” Thirty Years Later: Uncanny X-Men Giant Sized Annual Vol. 1 #11

Marvel Comics, November 1987

Writer: Chris Claremont

Chris Claremont wrote Uncanny X-Men for US publisher Marvel Comics from 1975 to 1991, a period of time comparable to peers in the French comic book industry but unheard of in the American comic book industry. Uncanny X-Men is a title about super-powered mutants, and under Mr Claremont’s penmanship, involved complex plot structures spreading out over years, soap opera romances, and deep characterisation of even minor characters. In many ways, Mr Claremont’s writing strategies deployed on Uncanny X-Men for those sixteen years could comfortably fit within the world-building ethos of contemporary manga like One Piece. The details of characterisation were more important than the plot, and the plot itself was allowed to boil for as long as it took to stew into an optimal result.

A hallmark of Mr Claremont’s writing was to give the characters very distinctive personalities and motivations. This was in stark contrast to the vanilla characterisation in effect in the bulk of the US comic book industry’s titles during that time. Superhero characterisation was typically a cookie-cutter of heroes saving the day against villains, and this continued through until the late 1980s (when the pendulum swung the other way and anti-heroes, such as First Comics’ The Badger, became in vogue). The only notable exceptions to this in the late 1980s were Marv Wolfman’s very successful run on New Teen Titans for DC Comics, Howard Chaykin’s sex-laden romp in American Flagg! for First Comics, Robert Loren Fleming’s underappreciated masterpiece Thriller (also for DC Comics, and which we have previously commented upon), and, perhaps curiously, the Pearl Harbour-fuelled vengeance and bitter, all-consuming patriotism of Roy Thomas’ All Star Squadron, also for DC Comics. Neil Gaiman’s ground-breaking work on The Sandman did not commence until 1989 and did not find its voice until the unique story, “The Sound of Her Wings”, in issue 8, August 1989. Setting all of these aside, the bleak, monotone landscape of titles such as The Avengers, The Defenders, Justice League of America, Infinity Inc, and other superhero titles were uniformly bereft of any genuine differences in the voices of these characters.

This particular issue, released thirty years ago in November, is in our view the high water mark of Mr Claremont’s work. It is a caper story which evolves into an Arthurian Grail quest. A caper plot is a sub-genre of the quest in literary form, but ordinarily involves a theft and a meticulous plain and distraction. Here there is a theft, but it is linked to a sense of desperation. The X-Men in this issue fight to save both themselves and the world.

The mutant superheroes reside in a mansion, and the story starts with the Canadian mutant known as Wolverine staggering home drunk late one evening.

Wolverine was at that stage not a household name as a comic book character. This comic was published long before the X-Men and Wolverine motion pictures which wryly educated a broad audience to the character’s excesses and foibles. A drunk superhero in the 1980s is a remarkable thing to consider. Societal standards in the 1980s, fuelled by the social conservatism of Ronald Reagan and the dampening effect of HIV/AIDS upon the libertine excesses of the 1970s, would not normally condone a character in a comic book. Comics in the 1980s, unlike superhero comics of the 2010s, were overwhelmingly orientated towards children. Opening this annual with Wolverine barely able to stand on his feet and reeking of beer was an exceptional gambit, as it might have easily sparked enormous protests from the readership’s parents.

As it evolves, the drinking binge is triggered by deep pain. The day marks the anniversary of what would have been his marriage. The inherent dichotomy of the character is laid out. Wolverine is a man who wishes to better himself. The character is a mutant berserker, armed with razor-sharp claws, his skeleton equally unbreakable, and his flesh capable of regenerating from the most grievous injury. Wolverine can inherently get whatever he wants through force. But he chooses instead to internally best his animalistic nature:

The drunkenness is thereby contrasted with the quiet, contained pain of the character. Each presents itself as one half of Wolverine’s dichotomous personality. The first half is the wild drunk, belching, falling onto his comrades, and staggering away. The second is the warrior struggling to achieve noble serenity. No other title in comic books at that time had such a high degree of precision in characterisation.

Elsewhere in the mansion, the mutant called Psylocke contemplates her own purpose. Why on earth is she on a team of mutant superheroes? As a telepath, she has no overt offensive combat skills. She does not understand herself or her role, and has a meaningful discussion about the topic with her brother, a superhero called Captain Britain:

Psylocke is an upper-class English debutante, invited into the ranks of the X-Men only because she is a telepath (and thus assists with communication between team members) and because of her brother’s star power. (Much later, the character was re-jigged as a ninja with a brutal offensive ability.) Being the equivalent of a mobile telephone exchange is a poor reason to be on a superhero team. Psylocke is physically weak – she would easily break a finger if she punched one of the X-Men’s usual gallery of tough foes.

The sudden appearance of an all-powerful alien called Horde is the catalyst for the story. After abducting the X-Men, Horde easily fends off their combined retaliation.

Psylocke’s telepathy confirms that Horde has “laid waste to thousands of worlds” and that his threat to destroy the Earth if the X-Men do not assist him is not an idle one. Horde does not mind engaging in cross-species sexual harassment as he sets the team on their mission:

Horde requires the X-Men to traverse a maze called the Citadel of Light and Shadow, thereby to recover a powerful relic – the Crystal of Ultimate Vision. The Citadel’s defence to theft is to offer every person who enters it their heart’s desire. This is the best possible defence – distract the would-be thief by what they most want and thereby remove them as a threat. The lure appears as images, visible only to the victim, in the mirrored walls of the Citadel. A mutant named Rogue is the first to fall:

Rogue is a character whose very touch causes her victim to collapse unconscious, and whereby she absorbs their superpower, memories, and personality traits. As a consequence, the character is described as living a very lonely existence, unable to so much as kiss a friend without immediate consequences. In those circumstances, it is little surprise that she is the first and easiest target for the Citadel, which offers her intense adoration contained within a fairy tale setting. The result of succumbing to secret fulfilment is corporeal non-existence.

Each X-Man, save for one called Longshot (a character with no sense of desire, and so is absorbed by the Citadel), is offered their heart’s content. For Havok, a character which can project plasma bolts, it is becoming an actual star. For guests Captain Britain and his wife Meggan, it is the quiet life with children in the English countryside. A mutant named Dazzler is offered a sad multiple choice: becoming a judge as her family intended for her, being a rock star as she always wished to be, or following her secret desire, failure –

It is a terrible and poignant insight into the character’s basement sense of worth. Being a celebrity musician does not stem Dazzler’s inherent self-doubts. The character is depicted as washed up into the X-Men, lost and joining the team through an absence of knowing what else to do or where else to be. A sense of belonging is the only motivation the character has in being a superhero. Absent that, Dazzler thinks she has no purpose at all. Nowhere else in mainstream superhero comics had a character been portrayed as a functionally depressed, until Frank Miller’s All-Star Batman (2005-2008, DC Comics).

The leader of the team, Storm, is offered the fun and adventure in Tokyo. As the team’s leader, she is the one who carries the responsibility of ensuring everyone gets through their often deadly missions. The lifestyle offered by the Citadel shears of the burden of leadership. She barely resists temptation.

Duty drags Storm back into the Citadel, but she retains her “party clothes” – a sign that the offer remains open, and that her heart is not sealed to the idea of endless crazy fun in Japan. This is a new insight into the character, not revealed previously within the title. Storm became leader of the X-Men after besting the previous leader, a mutant named Cyclops, in a friendly duel (Uncanny X-Men #201, November 1986). But leading the X-Men is plainly not her preference. Storm is the leader because she is best for the role, and not, as the vignette makes plain, because she desires the role. On the contrary, Storm desires the antithesis of responsibility. She would prefer to run away.

In the meantime, and in contrast, Psylocke discovers that she was meant for combat and pain. Her secret desire is to be made into a deadly weapon, one that everyone can see and which reflects her true self. The inner steel of her personality, forged in the tribulations of her past, literally manifest. She tears away at her own skin, in an horrific act that frightens her brother and sister-in-law:

As a sudden combatant, Psylocke is not whisked away to a dream scenario. She is instead left in the arena, ready to fight whatever danger is next.

Wolverine, for his part, is offered a particular scenario. A rough and tumble bar, with brawling and arm-wrestling, and Mariko, in leather and as a wild temptress, offering herself to him. But Wolverine rejects this as a sham. It is his heart’s desire, but he wants Mariko on her terms, and not his. And so he resists temptation, and avoids the trap. Further, he does not re-enter the Citadel’s corridors in the clothing he wears in the bar. Wolverine is in his costume. The rejection of the ultimate temptation is complete.

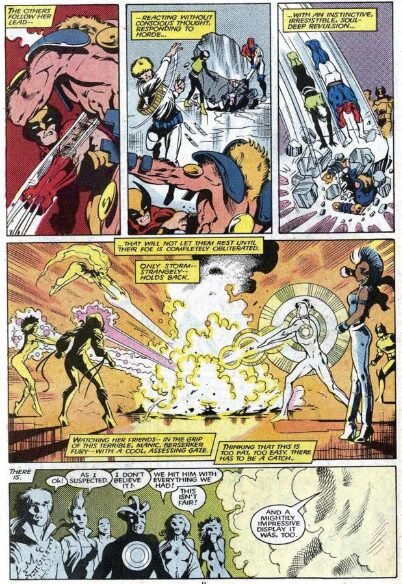

Horde sees that the team have almost made it to the Crystal, and comes at the survivors. It is then plain that the caper was actually sport for Horde. Psylocke offers to buy Wolverine and Storm time by trying to fend off Horde, knowing she will lose. Notwithstanding her telepathy and new metallic form, Horde brutally dismembers Psylocke. In order to save Storm from murder or worse at Horde’s hands, Wolverine pushes her into the mirrored wall, and Storm finds that this time she cannot resist her heart’s desire.

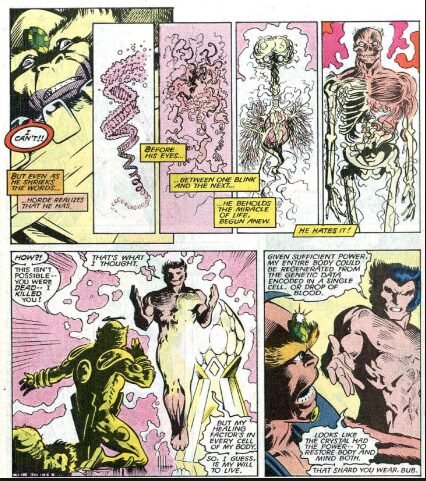

At this point, the psychoanalysis in the story ends. Wolverine is the sole survivor of the X-Men, and no match for the story’s antagonist. Horde leisurely impales Wolverine on a spear, and then mocks Wolverine as he tries to crawl and reach for the Crystal. It is out of arms’ length, and it seems that the X-Men have entirely failed. But then, Horde makes an arrogant mistake. He decides to tear Wolverine’s heart from his chest as a trophy. This causes a drop of Wolverine’s blood to spill onto the Crystal.

Wolverine undergoes a form of mystic ascension, not unlike the ascension experienced by Sir Galahad in the quest for the Holy Grail in Sir Thomas Mallory’s medieval story, Le Morte d’Arthur (1485, Caxton Press). Horde is quickly extinguished, leaving Wolverine to play with the universe.

Within the single issue, Wolverine has ascended from heart-broken drunk to God. But Wolverine’s sense of his own inherent failings, manifest at the beginning of the issue, compel him to realise that he is not fit to be ruler of the cosmos. Wolverine then destroys the Crystal of Ultimate Vision in order to prevent anyone else from using it and succumbing to its power. The story forms a complete circle.

There is a conclusion: the Citadel and the Crystal end up being a test created by higher powers, so as to ascertain a species’ moral fitness for evolution.

As stated above, this story represents the apex of Mr Claremont’s skills. In addition to the usual superheroic world-saving grandstanding, the story is imbued with repeated psychoanalysis of each of the players, and ends with an enormous character twist. Remarkably, the story is entirely self-contained. Each of the characters is nonetheless the subject of scrutiny in respect of their personalities and drivers. The examination of each character is contained in a psychological challenge, which almost all of them fail and, dramatically, die. Each of these challenges is captured in a small vignette which in turn is woven into the greater plot, where the parts jigsaw to form the whole. Observed from the perspective of structure alone, the story is a remarkable achievement, and thirty years on, is worth commemorating.