It’s Cold in the River at Night

Avery Hill Publishing, November 2017

Writer: Alex Potts

We have categorised this title as “horror”, although the terror in this story, written and drawn by Alex Potts, is so faint as to be almost ephemeral. Something is afoot here, but any fright is subtle. It is less than a ripple on the water. The faint touch is what gives this story its genuine chill.

It takes several reads to start to perceive its shape, distracted by what seems to be a straightforward vision. On the surface, the story is concerned with two people named Rita and Carl, who are renting a stilted house on a river. The house is the sole survivor of what is described as a multitude of similar houses along the river line. Two other neighbouring houses are described as having been entirely swallowed by an enormous storm. The house is only accessible by boat. Mr Beuf, the house’s owner and the captain of a small fishing boat, brings Rita and Carl food after a big storm, and admonishes them for letting their dinghy loose from its mooring. Rita is occupied with her thesis – it is due in a month. Carl turns his nose up and Mr Beuf’s gift of ham and bread, and decides to fish. He catches only a fish corpse.

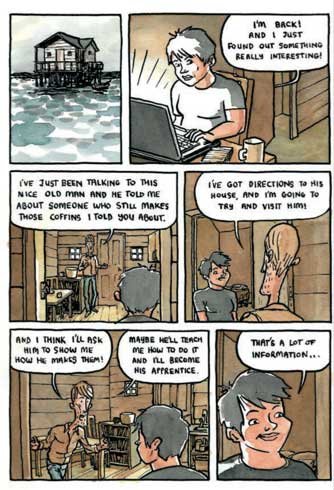

Carl is an unsympathetic character. He is weak-willed and prone to tantrums. The combination of finding an old book about traditional culture, boredom, and a visit to a local pub all leads Carl to a man who makes coffins. The coffins are very peculiar because they are in the shape of small boats. China, Japan, and other Asian countries were home to long-extinct cultures who used boat-shaped coffins. But this story, apparently set somewhere in Western Europe, describes the use of boat-shaped coffins as an element of a “traditional funeral”. Carl becomes an unpaid apprentice to the gruff and very reluctant coffin-maker. As time progresses and the purpose of his labours – planing old boards and removing rusted nails – remains a mystery, Carl becomes more self-pitying and unpleasant. He rails against Rita, and accuses her of having an affair with Mr Beuf (and, to be fair, Mr Beuf does make romantic advances on Rita, but she rejects him). Carl is then asked by the coffin maker to clean up an old wooden boat for use as a coffin. As the tide dramatically rises and a large storm approaches, Carl shields himself in the coffin against the elements. “What are you doing inside that coffin? Coffins are for dead people,” snarls the coffin maker. Scornful, he slams the lid shut, allowing Carl to drift away. Carl hallucinates while in the coffin and is eventually saved, but traumatised.

But is that all there is to it? On the first page, a young boy on a tour boat heading up river sees Rita and Carl on the stilted house, and waves. But the house is described by the tour guide as empty, and apparently no one else on the vessel see Rita and Carl. The river on which the stilted house sits is dead, and occupied only by a dead fish which has nonetheless bitten the hook. Wherever Carl goes, people stare at him. The book Carl has found is old and bound in leather, hidden behind a cupboard, filled with secrets. The dinghy floated away from the house, but Carl is utterly sure that he fastened it tightly – and so how and why did it become loose? The tide rises far too fast. The storm approaches and belts down rain, but the river sparkles and twinkles, untroubled in the serene moonlight, carrying Carl away. And trapped within the coffin, Carl sees his own funeral, and then Rita as a ribbon of light, an angel, and then his own life winding backwards, his memories as diminishing and multiplying squares.

There is nothing so blunt as a Neil Gaiman-esque ferryman here, despite the obvious symbolism of a coffin-shaped boat carrying the dead across the water. We glimpse archetypal rebirth through fire and water, but it is almost imperceptible. Mr Potts graduated from Hull School of Design (graphic design and animation) in 1997. Hull has a long-tradition of maritime trade and lifestyle and perhaps Mr Potts has drawn some inspiration from his surrounds during his studies. But what is clear is that Mr Potts learned at some stage to craft a story with such finesse, with such a slow creep, as to cause a reader to puzzle, re-consider, research, ponder, over and over again.