We are a year late in our review of the anniversary of Kingdom Come. It was published in 1996. Here, nonetheless, are the thoughts of two of our writers on the classic comic:

Kingdom Come (Review)

by Tom Kelly

American publisher DC Comics has a long publication history, largely in the superhero genre. Today, DC Comics often limits its more experimental books to its Vertigo imprint, but the recent rebranding of the superhero line under the title of “Rebirth” has been a hit for the company after the less popular “New 52” had turned much of their superhero universe into a gloomier place. Rebirth, by contrast, is going for a lighter tone reminiscent of many of the company’s past works. One such work would be the story Kingdom Come. Kingdom Come was at the time of its initial publication enormously popular and stays so today. Why is that? One could be led to believe that it became so as a work that defended the more optimistic, traditional superhero genre of decades past that, at the time of publication, would have been seen as quaint compared to the rise of violent anti-heroes, particularly coming from rival publishers Marvel and Image. Kingdom Come, on the other hand, features a group of characters in the form of superheroes Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman, along with ordinary human Norman McCay, find a way to reach beyond the violence of their era and embrace a more humane and morally upright way of doing things. The largely apocalyptic story ends with the protagonists realizing they can have hope and humanity, not through seclusion, but by reaching out to a common humanity and embracing the world in order to make it a better place.

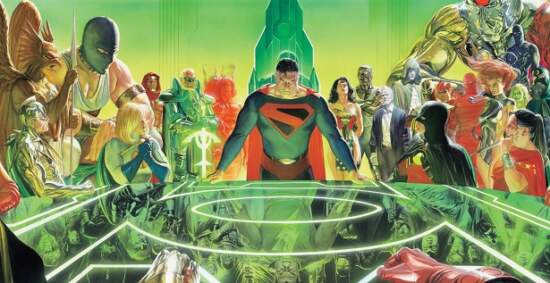

Kingdom Come is set in a future time period within the company’s superhero setting panorama. Written by writer Mark Waid with gorgeous artwork by painter Alex Ross, Kingdom Come depicts a subgenre, “superhero dystopia”, more often seen in Marvel Comics’ title, Uncanny X-Men, with its time-travelling, alternate universe characters. In Mr Waid’s world, where superhumans (often called “metahumans” in the story) have significantly increased in number. so much and Worse, without any sort of guiding moral code, that these superpowered beings y seem to simply run rampant in senseless battles against each other, with normal humans little better than collateral damage. The idea of simple human achievement is a thing of the past, as the reader learns that simple things like the baseball World Series and the Olympics have long since been forgotten as essentially meaningless. And through it all, the superhumans continue to attack each other for vague or unknown reasons.

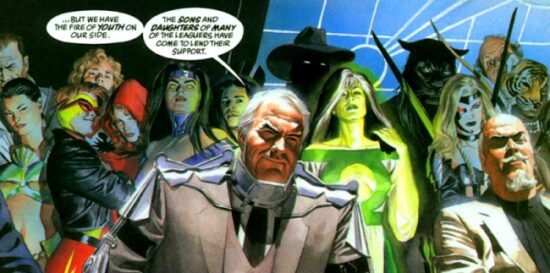

The problem, the reader gradually learns, is that the original superheroes, the ones that acted as inspirations and moral guides, have largely disappeared. This idea is mainly focused absence of leadership is most evident in on the character of Superman. A challenge to Superman’s legitimacy saw a challenger to, in essence, the right to be champion of the city of Metropolis, manifested in from a then-new character named Magog. Magog was depicted in Kingdom Come as an anti-hero character type more than willing to use lethal force. The deciding issue for Superman was when Magog murdered Batman’s evergreen adversary, the Joker. This occurred after the Joker had gone on a killing spree inside the offices of the Daily Planet, the newspaper Superman worked for in his other identity of Clark Kent. Among the dead was Superman’s wife, Lois Lane. Yet still Superman did not accept killing the Joker as an acceptable remedy or response to the Joker’s crimes. After Magog was acquitted by a jury, in a case where Superman himself testified against his rival. With opinion polls showing public support for Magog, Superman retired to his Arctic retreat, called the Fortress of Solitude, to live the life of a simple farmer in a geodesic dome.

However, Superman does not stay retired. He returns when Magog and a team of likeminded superheroes attack a villain named the Parasite, during as a consequence of which there was a nuclear explosion that leveled the state of Kansas., Superman is drawn out of retirement isolation by his old Justice League colleague, Wonder Woman. Unlike many of the older heroes, she seems to have stayed active for the past decade, though she is far from the only one. Most noteworthy, Batman is still active, though he is working through robots patrolling Gotham City. as he is Batman is personally reduced to using various braces to hold up a body that was abused for far too long in his war on crime.

The “Big Three” as they are often called are, for the most part, the main characters of this series, with two additional catalysts for actions. One is a longtime DC supernatural character, the Spectre, a murdered policeman’s soul attached to a powerful spirit’s body acting in the realm as the “wrath of God”. The other is Norman McCay, an older man and Christian pastor. The Spectre brings Norman McCay along to navigate, to witness events to ultimately decide who, if any one, needs to be punished at the story’s conclusion for the horrible atrocity that is coming. Norman knows this tragedy is approaching because he had been friends with Wesley Dodds, a 1940s superhero character known as the Sandman. Within continuity as it existed at the time of publication of Kingdom Come, Sandman was considered one of the first superheroes in the DC Universe, a man with a gas gun who had prophetic dreams. Upon Dodds’ death, the dreams started coming to visited Norman McCay, and as such, the Spectre needs McCay to act as a guide sextant and compass. As great as the Spectre’s power is, seeing the future is not among his many gifts.

The true power of the story comes from combining the talents of Mr. Waid and Mr. Ross. Mr. Waid possesses a near-encyclopedic knowledge of old superhero stories, and he can reference them as need be. Mr. Ross is an incredibly talented painter, creating new character designs for many different characters, often by giving out his imparting a of intriguing visions future look for of the older DC characters’ visual appearances. Many of Mr. Ross’ designs would eventually work their way into regular DC Comics superhero titles.

Both men are also known for an appreciation of past DC Comics stories, and essentially, Kingdom Come works as a validation of those stories. Much of the story is a reaction by Mr. Waid and Mr. Ross over the saturation of anti-heroes that proliferated in the American superhero lines of both DC Comics and its chief rivals Marvel Comics and in the early days of Image Comics. The character design for Magog is reminiscent of the Marvel Comics character of Cable, a cybernetic warrior from the future known for having scars, belted pouches (for no obvious reason other than paramilitary flavour), and some very large guns. That the conclusion of the story shows the heroes embracing their older values and working to really teach them to the next generation leads to a satisfying conclusion, one where heroes are heroic and only resort to violence as a last resort. This idea is demonstrated as Superman embraces the idea of being Clark Kent again, Batman comes out of seclusion, and Wonder Woman abandons the more violent path she had taken for the course of the story.

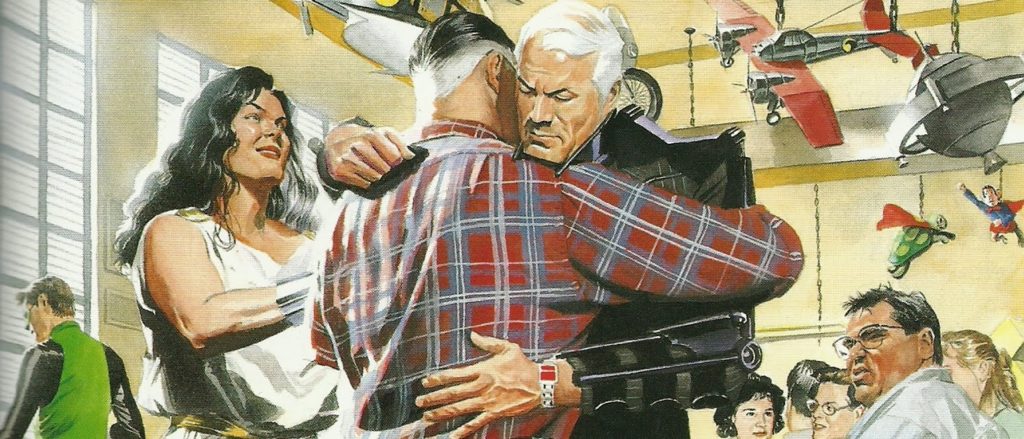

And it is only fitting that is the normal human, Norman McCay, who reminds everyone what that means. The finale of the story has a massive battle breakout in the middle of devastated Kansas. Superman and his allies had built a prison there to house all the meta- humans they have apprehended. But a prison riot inside combined with an attack by a brainwashed Captain Marvel on the outside, led the human leaders of the United Nations to order a nuclear strike on the battling superhumans. Captain Marvel sacrifices himself to stop the bomb, but the explosion still manages to kill most of the superhumans involved in the battle. Superman, initially thinking he was the lone survivor, flies off in a rage, and it is only McCay’s wisdom that talks him down from killing the assembled UN leaders. It is a story that reinforces Superman’s innate goodness and desire to help others and save lives, one where he would blame himself more for any failures that happened than other people. Superman and Batman rediscover their friendship despite differences of methods and outlook. Wonder Woman is about peace, not conflict. Heroes work with humanity, not over it. There is no better symbol for how that turned out than a single panel near the end of the story, where Superman for the first time in the series, dons the familiar pair of glasses that he uses to pose as Clark Kent and finally smiles.

Batman’s parents are killed, and he goes off to fight crime. Superman’s wife is killed – he hides in the Arctic. Who is the better man? Is there a proper comparison? Mr Waid has often written about Superman iterations: Irredeemable ; Axiom (a title about sacrifice and the delusions of superhero powers), Captain Kid and Strange Fruit. Superman is the lead player in this story. By going into exile, Superman stuck to his principles and would not budge on them, with the thing that ultimately drove him into hiding being the complete rejection of his values by the public in favor of Magog, a Biblically-named anti-hero more than willing to use lethal force. The darker colored costume could reflect a mourning period over Lois Lane’s murder, though it also references the 1940s Fleischer brothers Superman cartoons. Superman then refuses to use his human name until the end of the story. He insists on being called “Kal”. Interestingly, Wonder Woman accedes to this request while Batman refuses. Wonder Woman, likewise, is the only character to make much of a mention of Lois Lane’ death.

At the time of Kingdom Come’s publication, Superman’s origin story portrayed Krypton as a cold and emotionless place, and in the extraneous added pages set on Apokalips, the brooding demi-god Orion notes how often men become their fathers despite their best efforts. Superman here seems to think he can force his values on metahumans worldwide. But the whole time, he does not think of himself as a man.

Superman’s big change, after the cleansing rage, is to accept he is also Clark Kent. He accepts the glasses from Wonder Woman and actually smiles for the first time in the entire series. But if you ask who the better man is, Superman is partway to changing on his own when he allows Captain Marvel to decide whether or not to stop the bomb, but Norman McCay’s keen observations complete the process.

As for the other player’s importance in so far as Superman’s journey of realization goes, Wonder Woman is acting as an enabler. She is not helping him move on, though she has her own issues that prevent her from evolving. Batman has lived the tragedy of loss of loved ones, but he also offers no sympathy for his longtime friend, perhaps because Superman opted to just spend the previous decade in hiding. But McCay, after playing a largely passive observer next to an even more impassive Spectre, not only rises to the task in his calling as a pastor, a man talking to a god, and then reminding that god that he really is just a man. McCay brings peace to Superman and hope for himself, even helping the Spectre remember what it means to be human; he is bridging the gap between human and superhuman. The Spectre is there to punish the guilty, but it is McCay who points out there really isn’t any evil involved, just haste and misunderstanding over an escalating situation. (The only true evildoers were Lex Luthor’s group, all of whom were rounded up and punished with prison time. Though in terms of being a better man, it is interesting that Magog, a fairly minor character all told, really wants to change. He feels guilt for what he’s done and asks for punishment, and at the end is truly interested in the lessons Wonder Woman is teaching the surviving anti-heroes, personally administering a slap to the head to another man who doesn’t show interest in the Amazon ways.) McCay is the better man in this situation, someone who steps forward at a key moment with an open hand instead of a closed fist, who stands up to an agent of God when the time is right, and sees his purpose for seeing all that he did was to be that voice of kindness and reason when it was needed most. The rage is almost a cathartic moment. Bind anger leads to insight and acceptance. Norman McCay’s words are the trigger for that. That moment, cleansing Superman of the rage, allows the Man of Steel to stop being the cold and distant Kal and become instead the warm and welcoming Clark.

Moments like that tell the reader that, for this world and this setting, everything will ultimately work out., and Given how the anti-hero craze has, perhaps, extinguished, gone away again, then perhaps that is just as true for the reader as it is for the characters. Hopeful, optimistic heroes who do not resort to lethal force have a place in society again, and their stories can be just as good as the darker ones that were all the rage when Kingdom Come first hit shelves. DC often does best when it remembers its optimistic, altruistic storytelling roots. DC can get bogged down with stories about its own superhero continuity, but by and large it works best when it remembers and pays proper homage to its long history. The New 52 reboot did not do that, wiping the slate clean for much of the line but making the new versions uglier characters on a moral level. Rebirth started with long-absent Flash Wally West returning and noting the love was gone quite literally, as longstanding romantic couples did not really acknowledge each other. That started the change and the tone of the stories changed with it. Of the various Rebirth titles, The Flash is just lighthearted and fun, Wonder Woman is remembering her compassionate side, Nightwing looked into whether or not a new “partner” was a redeemable person, Batgirl is about a hip twentysomething in a trendy Gotham neighborhood, and as dark as “Metal” has been, a Batman title written by writer Tom King shows Batman accepting help from some new superhuman heroes in Gotham. Superman seems to be a more altruistic character through having a son, and Aquaman has firmly taken on the role of being a benevolent tyrant of Atlantis. At Marvel Comics, changes to characters like Iron Man and Dr. Strange are more the product of the success of the various live action movies than anything else. Thor (Jane Foster) is the ultimate in altruism, picking up the hammer knowing that it costs her a chunk of lifespan every time she does so. The new Korean Hulk seems fun and lighthearted. Iron Man is in a coma, but his AI is flippant and funny. Dr Strange is nothing but funny, light years away from muttering oddball spells with cheesy weight. Spider-Man (particularly the version with Miles Morales) is a fun title. (On the other hand, Captain America was recently perverted into a Hydra agent). It is worth noting however that some of these characters have been controversial with fans who do not care for what is perceived as mere politically correct replacements for classic heroes. But even our recent review of Huck suggests that superhero themes have returned to a brighter, more optimistic age.

To be clear, Kingdom Come did not predict the full circle so much as defended that style of storytelling at a time when Marvel Comics and the newly formed Image Comics were leading with anti-hero protagonists. Kingdom Come however is a response to 90s style anti-heroes, and it may not be that surprising that a number of writers working for Marvel Comics at that time were later crafting stories for DC’s darker-toned New 52. Kingdom Come was a defense, and the style is one DC seems to generally return to from time to time.

Kingdom Come is both a fantastic story as well as a promise, a promise that everything will work out fine and real heroes will return when we really need them.

_______________________

All the Rowboats: Kingdom Come’s Message of Death and Time’s Passage

by DG Stewart

Twenty-one years ago, writer Mark Waid decided to project his audience around twenty years or so into the future. Mr Waid wanted to consider the hypothetical exclamation mark on the never-ending battle of good versus evil. What if there was an ending to the perpetual story of DC Comics’ characters?

The superhero genre is a flotilla of boats on a river. So long as that river (of money, of commercial exploitation of intangible intellectual property rights) keeps flowing, the boats will keep sailing. So,unlike many other literary genres, the story’s characters (with rare exceptions) never see a conclusion. Batman will never recover from the grief of his parents’ murder. Superman will always fight for truth, justice and the American way. Wonder Woman will perpetually seek to bring peace to Man’s World. And if any of these characters do die in the fulfilment of their tasks, then inevitably they are brought back from Valhalla for another round (for the Flash, almost a quarter of a century later).

Mr Waid’s vision was Kingdom Come. An ending for heroes involves an apocalypse. The villain of the piece is named after a Biblical demon, Magog. The ultimate truth is brought about by a Christian preacher. The mighty are brought low in a flash of lightning and the fury of nuclear hell. There is even a villainous character called “666”, after the number of the Beast in the Book of Revelations. (The title itself, Kingdom Come, comes from The Lord’s Prayer – Matthew 6:9 and Luke 11:2 in the New Testament.) It is all very dramatic.

In this comic, many of the characters die. That should be remarkable, except that of course the story occurs in a future which will never come.

Many people have a great deal of affection for DC Comics’ characters. Some of them serve as role models for altruism. (The character Wonder Woman, a feminist icon in a bathing suit, was briefly an honorary ambassador for the United Nations, until protests apparently brought the tenure to a premature close). The inherent appeal of the story is that some of those beloved characters finally received conclusions to their never-ending stories.

Which raises the question: should some of these characters be allowed to die or retire? There are worse fates. Some suffer the oblivion of editorially driven non-existence. An alternate universe Batman’s daughter, the Huntress, and Teen Titan fixture Wonder Girl, were each were mangled up in 1987 and 1988 because their histories no longer worked, despite each being very popular. But Kingdom Come raises the question for those readers who have followed the adventures of characters for decades. Should some be allowed to end? Is it fair to a reader to see a character finally achieve their purpose?

This is perhaps underscored by Archie Goodwin’s character, Manhunter. Detective Comics issues 437 through 443, published bi-monthly November 1973 through November 1974, featured Manhunter as a back-up story. When Mr Goodwin finished up with Detective Comics, he was permitted by DC Comics’ management to allow the character to achieve his goal of stopping his shadowy nemesis, called The Council, and die in the process. The story was innovative and attracted many awards, but the death of the character, the sheer and unequivocal permanence, gave Manhunter a cult following. Forty-four years later and the character is still revered by older readers. When perennial favourite crime fighter Blue Beetle, refusing to betray his friends, was shot in the head by the villain Maxwell Lord in Countdown to Infinite Crisis #1 (2005), the same sense of mourning and respect for the character came into play. And for DC Comics’ imprint Vertigo Comics, Neil Gaiman meticulously plotted out the death of the title character of The Sandman, causing awe amongst the readership and a respect for the creative decision leading to the character’s suicide through that sense of tiredness of life which can envelope the very old. Why not invoke the same sense of reverence of death upon other characters?

Kingdom Come featured the deaths of longtime characters Green Arrow and Black Canary. Black Canary is shot in the head by HR Giger – inspired character Trix. Green Arrow cradles his wife while the nuclear weapon marking the crescendo of the story explodes. The two characters’ skeletons are seen in a final embrace when the dust clears. It is a poignant death.

The more significant of DC Comics’ pantheon of characters will be in existence so long as they continue to generate substantial revenue for their owner. Those boats will always be on the water. But others could finally retire. Here are some hypothetical examples:

a. Batman’s former protege Nightwing, unburdened by the same lust for revenge as his adoptive father, could marry, have children, experience happiness, and hang up the costume. Kingdom Come envisages this: Nightwing’s daughter Nightstar is clearly his offspring from a union with former partner Starfire.

b. Supergirl, entirely absent from Kingdom Come, but presumed to be the mother of the character with the clunky name Brainiac’s Daughter, might also have decided to retire and have a child.

So, why not? (Sotto voce, the fundamental problem of course is that writers and editors can, like Orpheus but no lyre and with less fuss, bring these characters back from the dead or from peaceful retirement. The Silver Age Flash was dead from 1985 to 2008. The Silver Age Green Lantern was dead from 1996 to 2005 – controversially being rendered into a villain before his death, and then a spirit of vengeance called The Spectre while dead.)

Many readers, who were much, much younger than their comic book heroes when they first opened a comic book, are now much, much older than those heroes. Age has only touched the audience. Kingdom Come reminds us that one day we will not be there to read the next chapter. Our heroes will outlive us. And it is sad that this should happen, for they too should also have the benefit of an ending. Our old friends should see a time when they reach their endgames, or heroically fall in battle. We should have a chance to say goodbye. Otherwise, as assets and not stories, they each suffer the curse, the price and consequence, described by Regina Spektor in her song, “All the Rowboats“:

All the rowboats in the paintings

They keep trying to row away

And the captains’ worried faces

Stay contorted and staring at the waves

They’ll keep hanging in their gold frames

For forever, forever and a day

All the rowboats in the oil paintings

They keep trying to row away, row away