The Wildstorm #2-8

DC Comics, 2017

Writer: Warren Ellis

We have previously reviewed The Wildstorm #1, and favourably. This should be no surprise to long-standing readers of the World Comic Book Review. Our reviews of British writer Warren Ellis’ body of work includes the brilliant Trees, James Bond: Vargr, Injection, and Karnak #1. Mr Ellis has never received an unfavourable critique from our staff. Entirely mindful that Mr Ellis would not care one way or the other of our opinion, the status quo of our approval changes with this critique.

Come in Alone

In 2001, Mr Ellis wrote a series of opinion pieces which were aggregated in a book, entitled Come in Alone. The columns were very influential in stripping away at the artifice of American mainstream comic book publishing as it existed during that period.

And at that time the American comic book industry was in a dire mess. Sales were in freefall, the market for comic books was shrinking, and the cultural relevance of the medium seemed to be at a point of no return.

Mr Ellis articulated the many problems in what was a public first for a comic book professional, and added his own idiosyncratic brand of venom around how the industry had let itself be hijacked by a consumer group of aging white men who had read superhero comics as children and would not let go of their love of men in tights.

Mr Ellis railed against the superhero genre, and its narrow vision, its fetishism, and its fans.

At the time of writing Come in Alone, Mr Ellis proposed what was then an avant garde solution. Strip the capes, masks, and costumes out of the industry, concentrate upon bringing new readers into the medium, and keep the creative essence of dynamism and action in a frozen plane which comic books uniquely deliver. “Rip from their steaming corpses the things that led superhero comics to dominate the medium – the mad energy, the astonishing visuals, the fetishism, whatever – and apply them to the telling of other stories in other genres. That’s all The Matrix did, after all.”

The metaphor is somewhat unfortunate because it inadvertently described Mr Ellis and his adherents as creative undertakers, and we will return to it.

(As an aside, what Mr Ellis could not have predicted in respect of the superhero genre was, first, the success of the ongoing television series The Big Bang Theory, which features four quirky scientists who are amongst other things ardent superhero comic book readers. That television show helped to slowly rehabilitate superheroes to the broader public as a concept other than worthy of ridicule. The Big Bang Theory conveyed the message that superheroes were still silly, but were endearingly eccentric rather than contemptuous. Second, Mr Ellis could not have envisaged the triumph of the business strategy of Marvel Studios. Marvel Comics during this period was running at a loss and had a terrible share price. In the pages of Come in Alone, Mr Ellis spends some time looking at the company’s dire financial reporting to the New York Stock Exchange. By any reading, Marvel Comics had to evolve or die. The business took the gamble of setting up a motion picture division, which licensed superhero properties to large film studios. This resulted in the remarkable success of the first Iron Man motion picture (2008), and spawned a succession of other superhero films based upon Marvel Comics characters. In 2010, Marvel Comics was purchased by monolithic entertainment corporation Disney, which has applied staggering sums to perpetuating motion pictures based on Marvel Comics’ superhero properties. As a consequence, the quirky genre of the superhero is as popular now as it was in the 1940s. This has sustained, albeit not radically improved, sales of superhero comics. Marvel Comics, as a comic book publishing company, almost seems like a research and development division, where concepts are road-tested and those which are viable are taken to a broader market by way of a motion picture or television treatment. And as a further aside, and we will discuss this another time, Scottish writer Mark Millar did predict the rise of the superhero genre, when interviewed by Mr Ellis in the pages of Come in Alone.)

The tangled weave

In his analysis cum rant in Come in Alone, Mr Ellis misses the most bewildering aspect of the genre. From the perspective of plot coherency, superhero comics are and remain a mess. The capes and masks are cliched, its true. But the fallacy of costumed crimefighters is not the worst of it. By reason of being never-ending franchises, writers of superhero-themed comic books are happy to grave rob other genres to keep their stories fresh.

DC Comics’ Batman, for example, has certainly been the subject of many noir crime / detective stories. But the character is also frequently used in espionage stories, horror stories, science fiction stories (including historical epics thanks to either the twin devices of time travel or parallel universes), fantasy stories, even romance stories. The character has been around for eighty-odd years: of course, inevitably, some writer or another during that period of time is going to think that Batman versus Dracula is a good idea. But what that means is that the inherent integrity of the original concept, a masked detective, is conceptually tangled.

An integration of absurdities

But it goes further. Long ago, writers formed the view that teaming up Batman with an omnipotent alien refugee, an Amazon princess, an intergalactic policeman, a scientist who can run as fast as light, and a shapeshifting Martian was also a good thing. Each one of those concepts by itself is fertile ground for creative output. But smashing them together produces a less than desirable result. The evolution of the team-up, where two or more superhero characters interact, into an endemic indicia removes any sense of a singular coherent theme within the superhero genre.

Looking by way of comparison at the evergreen superhero character Spider-Man, it is one thing to suspend disbelief so as to imagine a boy has gained the abilities of a spider as a consequence of being bitten by an irradiated one, and how he then deals with this unique development. It is another to think that the boy with spider-ish abilities hangs out in Manhattan with a Norse god, a billionaire in an armoured battle suit, a World War Two icon, and so on.

Marvel Comics’ Wolverine, for another example, has come to be defined by how the character interacts with other Marvel Comics’ characters – the peer relationship with Captain America is significant, but why should the story of a Canadian mutant drifter with surgical enhancements should have anything to do with the ultimate American icon? Or with Spider-Man? Or The Punisher? In mainstream American comics, gods and aliens and billionaire vigilantes and science-experiments-gone-right-or-wrong all casually intermingle with no reality check. No one blinks when the King of the undersea nation of Atlantis drops by. The chaotic creative jumble is de rigeur.

Most recently, and controversially, DC Comics have foreshadowed the integration of the characters in Watchmen, a stand-alone masterpiece, into its broader continuity. The body of concepts has its own gravity well. Even Watchmen, regarded as one of the best novels of the twentieth century by Time magazine, cannot escape.

No coherence

Indeed, it is fair to say that the much (but not all) of the superhero genre is characterised by being a complete and utter mess of concepts, with the only division being ownership. Each is a body of concepts: there is no singular concept divisible in the bundle. Each, in so far as they have the same owner, are intertwined to the point of indivisibility. Each are stacked upon each other, whereby the genre is the concept. Even when a new character is introduced, one of the first considerations is how the new character fits within the body of concepts.

This partly stems from lazy writing (why bother with a thoughtful plot if instead sales will increase because a title character is interacting with a popular character in a crossover?) and from the perception that integration of concepts increases sales. What it does do is cause one coherent suspension of belief to be mashed into a fuzzy smear, with multiple suspensions of belief all co-existing and interdependent.

The sum of the concepts is less than the whole.

The superhero comic book pretending not to be a superhero comic book

What Mr Ellis has done in The Wildstorm is to retain this worst aspect of superhero comic books. The capes and masks are indeed gone.

But the messy bundling of concepts remains. In this title we have:

a. aliens;

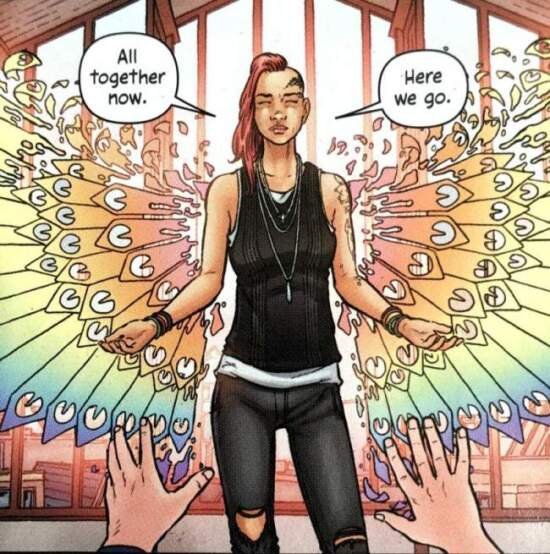

b. a mystic shaman with magic powers;

c. a planetary defence system (manifested as an Anglo-Asian woman) also with magic powers;

d. a self-made cyborg;

e. a spy theme of assassins and counter-espionage agents;

f. a science fiction component consisting of an orbital space station;

g. tension between two secret cabals;

h. a woman who seems to have been transformed into some sort of faceless humanoid with the ability to teleport;

i. an assassin who finds he can melt things with his fingers, probably because of a brain tumour.

Any one of those concepts would carry a story. But stitching them together into a body of concepts is straight out of Frankenstein’s manual.

Given the very broad warrant granted by the characters’ creator, Jim Lee, Mr Ellis could have departed from that. Trees is a singular and unique science fiction concept. Mr Ellis’ work on the James Bond franchise is pure espionage. But Mr Ellis did not.

The plot of the title is ostensibly interesting. In the epilogue to the collected edition of issues 1 to 6, Mr Ellis states that he deliberately set out to replicate the competing factions of the HBO fantasy saga, Game of Thrones. This Medici paradigm manifests in this title as an elaborate chess game between the three major players, the Halo Corporation, Skywatch, and IO, with some random outliers as catalysts for trouble and disruption. This would have been a corporate conspiracy story with some espionage and paramilitary action thrown in for good measure.

But in The Wildstorm, each faction features characters with powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal men, each embodying a different concept, a different origin, a different raison d’être. Why did Mr Ellis, given enormous parameters in his reworking of the 1990s characters, decided to stick to this fundamental contortion, dolloped out of the superhero blender?

Mr Ellis served up the same dish for Marvel Comics in 2008. It was a similar exercise, taking a defunct set of superhero concepts and tweaking them. In that instance, New Universe became New Universal. In this instance, Wildstorm Comics has been rendered as The Wildstorm. To adopt Mr Ellis’ metaphor of corpses in Come in Alone, in both examples, Mr Ellis has taken the dead and only slightly putrid superhero concept body, and filled it with embalming fluid.

Mr Ellis has fallen into the same trap he identified in 2001. He has applied the superhero formula. Mr Ellis’ formula has a number of idiosyncratic variables:

a. Some of the characters have changed ethnicity. Deathblow, also known as Michael Cray, is now black, as is John Holt (once an android called Spartan) and Priscilla Kitaen (a shapeshifter called Voodoo). Jenny Spark is now a Chinese-British woman called Jenny Mei Sparks. There is also one gender-switch: Jackson King is now Jackie King. Mr Ellis has always been concerned with racial and gender diversity in his comics.

b. The use of suggestive, mystique-creating terminology. Characters or groups which are unaligned or have changed allegiances are “wild” or “in the wind”. The Engineer has a “trans-skeletal dry suit” and takes refuge in a “Majestic-level shelter site”. An assassination team is called a “Black Razors CAT”. A dead man with extra fingers has engaged in “home brew gene editing.” “Proximity-driven polonium diffusers” is derived from the Russian and North Korean penchant for assassination by way of radioactive material.

c. Mr Ellis’ trade mark laconic humour. There’s no posturing moralism in any of the dialogue. These is respect of altruistic behaviour, but it is infrequent.

But we have seen all this before too. Mr Ellis has deployed all of these things on many occasions in the superhero space. (And indeed, in respect of Jenny Mei Sparks and The Doctor, there is some unequivocal tomb raiding by Mr Ellis of his own work on The Authority, a title he created back in 1999 and which was then a publication of Mr Lee’s comic book company, called Wildstorm Entertainment.)

Stitching together these old concepts into a new body and trying to reanimate them is an exercise in zombification. It is beneath Mr Ellis’ talents.