Yoga Joe #1

Writers: Dan Abramson and Chris Mead

Brogamats LLC, 2017

Yoga Joe is an independent publication written by Dan Abrahamson and Chris Mead. The comic can be purchased at www.yogajoes.com. This is a strange website. It not only offers the comic, but also offers green plastic toy soldiers. Instead of firing guns or engaging in bayonet charges, the plastic toy soldiers are cast in yoga poses. The toy soldiers have nothing to do with the comic, but they are so strikingly unusual that they are worth mentioning nonetheless.

(Yoga + War) x Fun

Fusing a story about a war veteran’s turn to yoga together with a tale about martial arts fights with futuristic battle-bots is not an easy accomplishment. The only way this could be done without a descent into ridiculous pretention is to imbue the story with fun.

The copy for this title reads as follows:

“Deep in the Himalayas, a US Marine searches for meaning. When Joe happens upon a mysterious temple, he discovers an order of yoga-practicing monks who could help him find some peace. But this place also conceals a powerful secret – a force that can be harnessed for incredible good, or unspeakable evil. When a savage corporate army attempts to destroy the temple and steal its power, Joe must join forces with other warriors, focus his strength, and yoga harder than he ever has before… the world depends on it!

Packed with action and adventure (and kick-ass yoga!), this is the origin of a new hero the world needs – if he’s not already too late.”

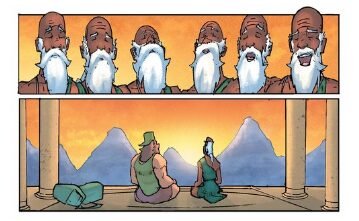

At seventy-four pages long, this comic, Yoga Joe (not G.I. Joe) is a bulky first issue. But it is an easy read. It does not take itself at all seriously. The induction of the main character, Yoga Joe, into life at the yoga hideaway (called the Namestery, rather than a monastery), is jaunty and mild. Joe’s interactions with the other three Americans seeking peace at the Namestery is filled with gentle jibes between the characters. The attack by the sinister Red Panda Corporation, a company seeking to forcibly remove the Namestery and its occupants from their secluded location, is conducted by men in armoured and powered suits: the combat involves the defenders of the Namestery dissembling or destroying those suits. This is a tactic deployed by writers who wish to show carnage but not the type which involves harm to living things. This very often written into battle scenes in the cartoon Star Wars: The Clone Wars which features the beheadings and dismemberment of robots. The robots are slashed to pieces with lightsabers, but not a drop of blood is shed. This cautious delivery of violence is very evident in this title.

And there is a focus on breathing. It is all quite odd. And yet, because of the mild humour, it works. The element of humour is not evident in the promotional copy, which seems to us to be a marketing oversight.

Warrior Culture

We have previously noted the recent realignment of the US comic book industry to the military class within the United States. In our review of Ragman #1, we noted:

“Warren Ellis appears to have been the first comic book creator to notice how many soldiers appear as superheroes in contemporary American comic books, when he wrote Avengers: Endless Wartime for Marvel Comics in 2013 and expressly observed that almost all of the core team of the Avengers superhero group were soldiers (Captain America, War Machine, the Falcon, and Captain Marvel), warriors (Thor), spies (Black Widow), or involved in the defence sector (Iron Man). (DC Comics’ characters Batwoman and the Green Lantern Hal Jordan are also ex-military.) The website FiveThirtyEight.com noted in 2015 that 1.4 million people are currently serving in the US military, around 0.4% of the population.

“But further, As of 2014, the VA estimates there were 22 million military veterans in the U.S. population. If you add their figures on veterans to the active personnel numbers mentioned above, 7.3 percent of all living Americans have served in the military at some point in their lives. But since only 2 million veterans and about 200,000 current personnel are women, that overall percentage varies a lot by gender — 1.4 percent of all female Americans have ever served in the armed services, compared to 13.4 percent of all male Americans.”

This means that a significant percentage of the traditional demographic for superhero comics – young American men – have served or are serving in the military. This leads to a natural instinct for US publishers to render or re-render characters as military personnel or veterans. The most obvious example of that was DC Comics’ treatment of John Stewart, another Green Lantern, whereby the character was no longer an architect but was instead a former Marine sniper.”

Here, four of the protagonists are ex-US soldiers of varying pedigrees. But there is no sense of societal status elevation arising from the military backgrounds of the characters. Instead, where the master Yogi and the balance of the yoga students are pacifists, the four retired soldiers are the sole defenders of the Namastery by default. It just so happens that they are the best possible defence by way of their respective backgrounds.

Initially, and mostly because of the marketing copy, we were of the view that the writer was sardonically mixing the counter-pretension of yoga and meditation with the machismo of military service. The trained violence of the armed forces is far removed from the trained serenity of yoga and meditation.

The objective of the comic however is clear in an advertisement at its conclusion. The writers of the comic are endeavouring to draw attention to a yoga program for military veterans. Trying to bring peace to those who have been exposed to war is as good a reason for the existence of a comic as any.

But notwithstanding that noble cause, this is a fun read.