The popularity of Asterix – “Asterix et la Transitalique“

Orion Children’s Books, 2017

Writer: Jean-Yves Ferri

We have previously written about the historical inaccuracy of Asterix. But we have not addressed the question: why is a story about two Gauls fighting Romans two millennia ago so popular? Thus far Asterix has spawned seven French language movies, a lucrative merchandising business and a theme park outside Paris that has 2 million visitors every year.

In The New Statesman, Ian Sansom writes, “Asterix is clearly for children, and for losers: it depicts a world where ungovernable appetites are momentarily sated and fulfilled… Asterix, with its absurd levels of comic-book violence – all those swirling stars and sticking-out tongues, black eyes and bumps to the head – was for anybody and everybody. It was the sort of thing you actually wanted to read… the plots are simple and the end result is always assured: the Romans are always beaten, there is always a banquet. Every Asterix album is really just a copy of the very first one, Asterix the Gaul (1961). Nothing changes.”

This explains the reason for its global popularity (except for the United States, where it is more or less unknown). But what about its enormous popularity in France? The issue is framed as one of cultural superiority by Time Magazine:

“Many people in France talk of the “Asterix syndrome” and the “village gaulois” (Gallic village), the idea that tiny, embattled France needs to defend itself against the encroaching cultural influences of the U.S., or the English language, or both. Usually used pejoratively, the terms indicate an inward, backward-looking way of seeing the world. The sentiment is also tied up with the French obsession with its cultural exception, the various rules and regulations designed to protect the French way of life from outside forces: French singers must sing in French, English words are banned from advertising, half of all TV shows on air must be European, and so on. It’s no surprise that France’s colorful antiglobalization activist José Bové, who happens to sport a Gallic handlebar mustache, has been dubbed a modern-day Asterix for his campaigns against McDonald’s and genetically modified foods.”

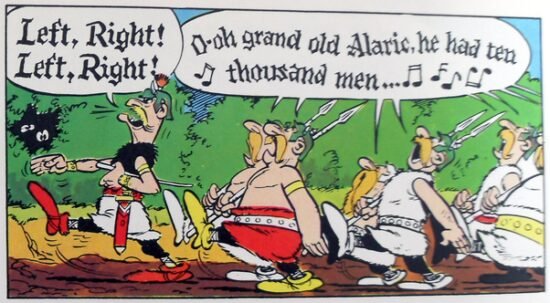

But there is also a suggestion of revisionist history. Asterix was devised in 1957, just as Charles de Gaulle had become president of France and French disengagement from its Anglophone allies was underway. France was humiliated by German invasion and rule during World War Two, and many French people had become collaborators with the invaders. A cultural recalibration of the importance of French resistance was welcomed. The conquering Romans are the main oppressors in Asterix books but there is unmistakable aggressive presence of the Germans, as Visigoths:

In Asterix, France was not depicted as the colonial power struggling to keep Algeria in its grasp by way of armed suppression between 1954 to 1962, but instead has a faux ancient history of rebelling against foreign aggression. Asterix proposed that France was to be commended for its resistance against the Germans and its departure from American hegemony, and its struggles in Algeria were ignored. Writing in the New York Times, Ana Riding has broader insight: “Being hapless is, of course, part of the joke. The idea is that like the French, the Gallic villagers spend their time arguing and eating. But when threatened, they unite and magically (thanks to a magic potion) defeat the enemy. That the lessons of recent French history suggest a different outcome is not the point. ”They’re like us, exasperating but endearing,” one French woman said. ”Asterix is our ego.””

In any event, Asterix et la Transitalique (Asterix and the Chariot Race in English) is the 37th book in the Asterix series, and the third to be written by Jean-Yves Ferri and illustrated by Didier Conrad. Much of the action takes place in Ancient Italy, where Asterix and Obelix meet the original inhabitants of the Italian peninsula: the Italics. Like the Gauls, the Italics are seeking to keep independence from Rome. The theme of cultural autonomy is a constant. The book was released worldwide in more than 20 languages on 19 October 2017 with an initial print run of 5 million copies.