A City Inside

Avery Hill Publishing, 2016

Writer: Tillie Walden

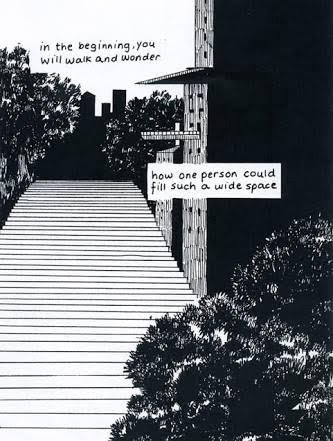

Time. It starts with a woman, lying on a very soft mattress, offered some tea. There is a sense of therapy, of mediation being introduced to a reluctant novice. And then, she is told to breath.

With that breath the protagonist is stolen from the stilted prelude and shuttled into another life, either an alternative reality or a projection into the future of her current reality. There is something a little transcendental about the mechanism which starts the bulk of the story, a sense of a deliberate initiation of a process of insight by hallucination.

“Bulk of the story” is a misnomer as to the weight and cadence of A City Inside. The story is instead a light autumn leaf propelled up and down by a random breeze. The text is sparse, economical, and ephemeral in its message. Indeed, it is not so much a story as a narrative poem set to images.

The creator of this work, Tillie Walden, is concerned with time and its passage. She starts with the protagonist’s childhood.

“You grew up in the same way the weeds did around the garden. Thin and unkempt. Bunching together to find a form….You left when you were fifteen. Trying to escape those Southern ghosts.”

It is nonetheless a happy childhood, lonely, but filled with books and space. The protagonist follows the path of an adult, well-worn by expectations, life in a city.

“You were too afraid to live in the city. Even though you knew that is what you were supposed to want. All you wanted was quiet. So you decided the sky would be better and began to live there.”

What is the sky a metaphor for? It is hard to say. The story uses it as the panorama of a sense of freedom and of splendid isolation. The clouds in the sky, milling about the capsule the protagonist has built around herself, also allude to the story’s meaning, capable of perception by a reader but impossible to grasp. We can see the clouds. But unlike the protagonist, we cannot exist amidst them in the sky. We could not.

And then, the protagonist meets a beautiful woman. She arrives through the air on that most modest of vehicles, a bicycle.

“You never understood what she saw in you. She didn’t leave your side and that was enough. You gave up the sky for her. You can no longer watch the clouds and planets over breakfast. You find yourself looking out the same window every day.”

Bicycles are entirely unsuited for travel through the sky, after all. With relationship come sacrifice. The next three lines are telling:

“ I know. It doesn’t feel right. You don’t want this kind of life. But you want her.”

The compromises of a relationship become too much. The protagonist departs, compelled by a nameless inner drive, and leaves with her lost lover the best gift she can, Nancy, a wonderful cat. There is a sense that nothing could anchor the protagonist.

The relationship ended, there is a sense of introspection.

“All the wounds inside you. Everything from the spirits of your old home. To the hours alone in space. To the emptiness you left behind.”

But are not those wounds self-inflicted? Is the craving for space and elevation, the side effect being loneliness, just the outcome of her own desires? And precisely what emptiness was left behind? Love, and the loyalty of a cat, is something more than a cloud.

And then, a moment of catharsis. The woman is screaming, with fists clenched, into an empty room. She confronts the void. “Until finally… they crack open, like a chunk of ice. A massive space will form.” And these words sit alone in the blank sheet of the page.

Creeping up the right hand side of the page, “a new city will be built.” Buildings and houses slide into existence. The protagonist goes to live in the great empty city, where the corners talk to her. “You’ll realise you’re a queen.”

The sense of hallucination is underscored by the art. Koi fish float in the air. There is a strong sense of ethereal existence. But memory intrudes into the artifice of isolated glory. “And when everything starts to slow down. And your eyes shift upwards. You’ll remember the tangled weeds that scratched your ankles. You’ll remember the warmth and weight of Nancy sleeping on your leg. You’ll remember her laugh. And the way she never seemed to forget anything you ever told her.”

The cost seems high. Age visits the protagonist. It cannot be undone.

And the dream ends. The woman who lay on the soft mattress stands up and puts on her jacket. She leaves the room. Outside is the beautiful woman of her dream. They walk away together.

Can it be undone? Which is the dream and which is the reality? Is this autobiographical? The story could be a cautionary tale sent back through time: the older version of the protagonist warning her younger self that her needs, the desire for space, to be the queen of a creation that cannot inherently be shared, has consequences.

Rien por moi. This is a beautiful story with nuances that set the mind ticking for hours after it is set down. More information about the author is available at TillieWalden.com