Too busy to go to law school? No problem: here, your favourite comic book characters give you a primer on what intellectual property law, that oddball bag of rights that underpins everything from advertising to comic books to aerospace innovations, is all about.

1. Trademarks

(Marvel Superheroes’ Secret Wars #7 (1984-5))

Spider-Man is correct: a registered trade mark (or “trademark” if of North American persuasion) operates so as to prevent a third party from using a brand which is identical or substantially identical to the owner’s brand.

If he had a registered trade mark, Spider-Man could have rushed off to court (assuming for a moment that there was one on the artificial planet of Battleworld, where this story took place) and obtained an order for an order requiring Spider-Woman to cease using the name.

Other remedies for trade mark infringement include damages (although it is difficult to see what sort of financial loss Spider-Man has suffered in this instance) and an account of profits (Spider-Woman has made no profit in her use of the brand, which ends that too).

Trade mark registrations are a type of statutory monopoly available in almost every country. Suffice it to say, given the value of the brand, Marvel Comics has “SPIDER-MAN” registered as a trade mark more or less across the world.

(We have previously discussed the curious story of how DC Comics and Marvel Comics have joint ownership over the word “SUPERHERO” – a right effected by trade mark registrations.)

2. Patents

Patents are another form of statutory monopoly right, granting exclusive ownership over new innovations. The two usual elements for a successful patent registration is that the invention must be novel (new) and have inventive step (the awkward and artificial test that the invention would not have been discovered by someone skilled in the art of the particular technology but lacking the spark of imagination).

Unlike trade marks (which upon renewal, and in some countries, use requirements being met, are perpetual), patents typically last for only twenty years.

Superman’s arch enemy Lex Luthor has here allegedly purloined an aerospace patent:

(Detective Comics #33, 2003)

Batman grumbles quite rightly about the cost and duration of patent litigation – it is seriously expensive, no matter where in the world it takes place. It seems it is a daunting proposition for billionaire crime fighters. The very first thing that a defendant does is to counter-attack and try to invalidate the patent, adding to the expense.

3. Copyright

The essence of copyright is there in the name: “the right to copy.” Copyright needs to be original and “reduced to material form” – in other words, copyright will not protect a concept, only the concept as expressed (in writing, as a drawing, as a sculpture, as software code, or in some other form of expression).

(Doom Patrol #11, 2018)

Here, the Doom Patrol’s quirky adversary is, apparently, too close to some other comic book character, and the writer has decided to turn this into a laconic statement on copyright.

The determination of what is “too close” differs from country-to-country, but in most places it is a side-by-side comparison. Many of the characters appearing in US superhero comics are uncannily similar to each other, and so the writer makes a valid point.

4. Confidential Information

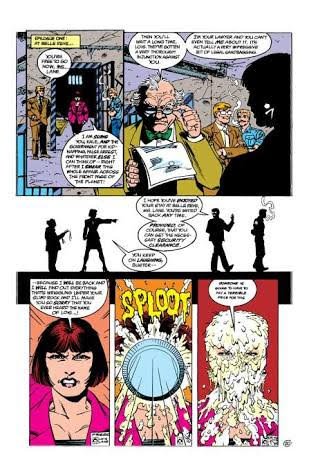

(Suicide Squad #30, 1989)

Reporter Lois Lane finds herself tied up in knots by the US Government, unable to reveal the confidential information she has gleaned from her involvement in the Janus Directive, a fight between clandestine superhero government agencies in the pages of Suicide Squad.

In some countries, confidential information is protected by statute (in the US, for example, the Protect Trade Secrets Act and the Economic Espionage Act), and in others, it is a “common law” (judge-made) negative right – a right to prevent the disclosure of confidential information. Sometimes these are effected by contracts called non-disclosure agreements, and sometimes the facts are plainly confidential and do not need an agreement to obtain the intervention of a court. Clearly, here, watching competing secret government super powered agents try to kill each other was plainly confidential. (The cream pie in the face is not a usual court-sanctioned remedy.)

Disclaimer: this isn’t legal advice. If you’re getting legal advice from a website devoted to comic books, you’re really in the wrong place.