The superhero genre of comics has a musty American origin. It dates back to the late 1930s, to a time when superheroes were considered to be a booming cheap media fad and not a genre. Contrary to expectations from the turn of the millenium of the end of the industry, superhero comics have been revived over the past ten years, mostly because of the unexpected popularity of Marvel Studios’ motion pictures. Publication remains overwhelmingly dominated by the two major American companies, DC Comics and Marvel Comics.

The American love affair with cars is better understood. It dates back to at least the popularisation of automobiles: the Model T Ford was first released in the 1920s, a decade prior to the appearance of superhero comics. Approximately 6.3 million passenger automobiles were sold last year in the United States.

Both superhero comics and automobiles have a long history of mass consumption, each approaching a century of popularity within the United States. Both traditionally have a whiff of testosterone about them. What happens when superheroes and cars are brought together?

Surprisingly, there are very few examples of cars as a centrepiece of superhero comics. Here is our brief survey:

1. The Batmobile (DC Comics. First appearance: Detective Comics #27, May 1939)

DC Comics’ master strategist and crime fighter Batman famously gets about his home town of Gotham City in the Batmobile. It is perhaps the world’s most famous fictional vehicle.

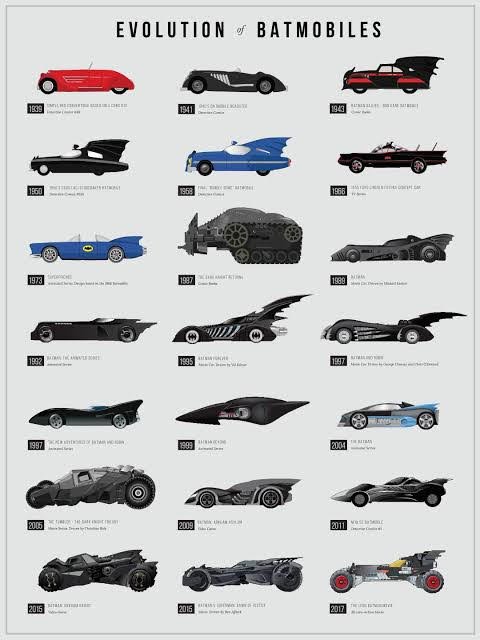

The Batmobile has changed configuration many times over the decades (see the infographic). Indeed, the first Batmobile was a red roadster:

There are two iterations however which are iconic: the original roadster version featuring a stylised bat’s head over the radiator, and the customised Futura which appeared in the 1966-67 Batman live action television show and which was adopted within the pages of comics.

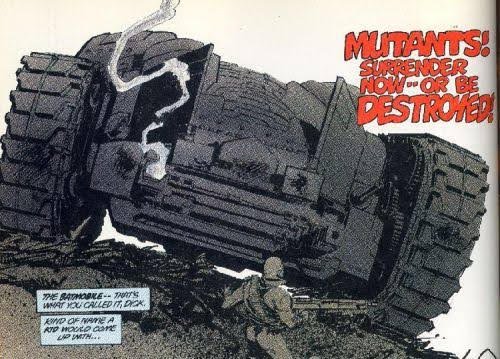

(There is also the tank which appears in Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns – technically, not a car, but called the Batmobile.)

The Batmobile has a variety of helpful features, but mostly it is fast, bulletproof, and usually stealthy.

2. The Spidermobile (Marvel Comics. First appearance: Amazing Spider-Man #129, 1974)

Why the inhumanly agile and mobile superhero Spider-Man, who can travel busy city blocks in seconds by swinging above traffic, could possibly ever require a car has never been clear. Writer Gerry Conway explains its origin in an interview:

“This was a notion that Stan had. Stan was put in an odd position because he moved up from being an editor/writer to being the publisher of Marvel Comics in 1970-71, and as a result of that, his priorities towards how to find revenues for the company changed,” Conway said. “He was approached by, I think it was Hasbro, or it might have been Tonka Toys or something, who said, ‘Listen, we found that what really works for toy characters, in addition to the figures, is if they had a lot of cool stuff with them. Could you maybe give each of your characters a cool car?’ And so Stan said, ‘Sure!’ He didn’t have to do it. He told me, ‘You know, Spider-Man needs to have a car.’ And I’m like, ‘You do realize that Spider-Man swings on a web between buildings and the car would really slow him down doing that?’ and he said, ‘I don’t’ care what you do with it, just do it.’ So we played it for laughs and we sank it in, I think, the same issue.” (SDCC: Spotlight on Gerry Conway. Travis Fischer, Contributing Writer.)

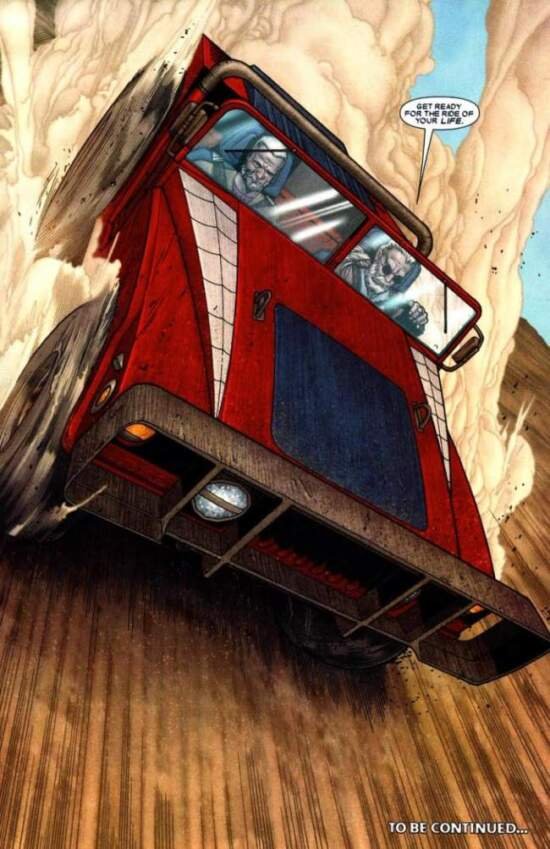

Spider-Man’s Spidermobile had only a brief appearance in the 1970s, before being recycled for use in the dystopian adventure Old Man Logan (2008).

The Spidermobile has uncanny properties: it can shoot webs, drive up walls, and make tremendous leaps.

3. The Arrow-Car (DC Comics. First appearance: More Fun Comics #73, November 1941)

Green Arrow is a superhero which first appeared in 1941, some three years after the first appearance of Batman. Batman had a teen sidekick called Robin, and Green Arrow had a teen sidekick called Speedy. And thus we see a shameless copy of the Batmobile, the Arrow-Car.

4. Nemesis’ Audi (Icon Comics. First appearance: Nemesis #2, September 2010)

Iconic cars within superhero comics are even harder to find in more recent times. Mark Millar’s evil mastermind Nemesis hunts various police chiefs around the world for sport. The title Nemesis was a limited series published in by Icon Comics.

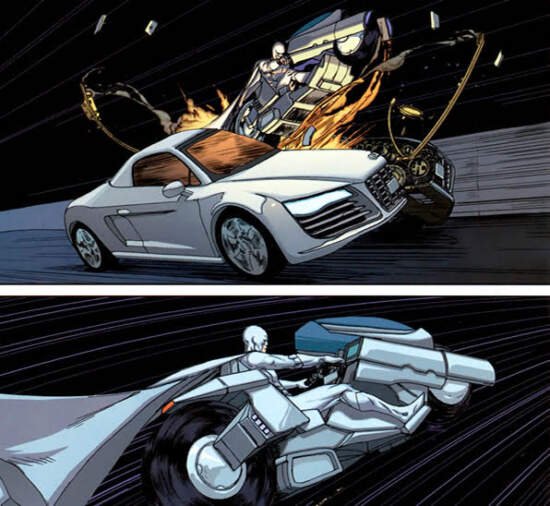

While being chased by an army of policemen in Washington DC, Nemesis drives a white Audi into a roadblock. Nemesis makes the car leap into the air, and the Audi splits down the middle. Inside the Audi is a white motorcycle, and in the column of the motorcycle is an enormous machine gun.

Nemesis is filled with surprise after surprise, and the sudden transformation of the title villain’s car into a mobile cannon is yet another audacious twist to the blockbuster plot. Whether German car manufacturer Audi were ever aware of the appearance of this lethally modified Audi in Nemesis is unknown.

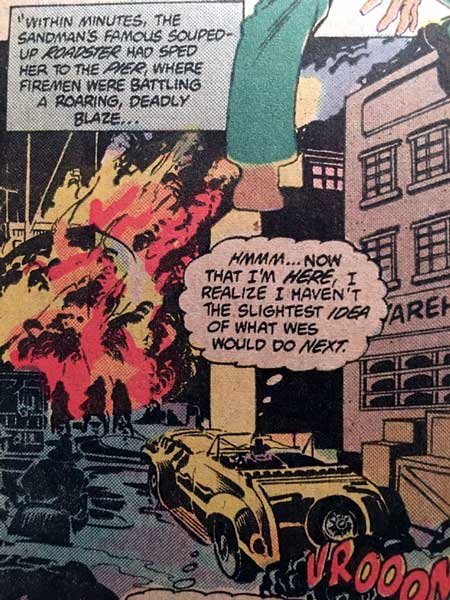

5. Sandman’s roadster (DC Comics) First appearance:

A masked detective first appearing in 1940, the Sandman drives around in what is described as a highly distinctive roadster.

The Sandman is secretly Wesley Dodds. Dodds has an ongoing romance with a woman named Dian Belmont. Much later in her publication history, in the 1990s comic book series Sandman Mystery Theatre, Dian Belmont is a feminist extrovert who slowly falls for the bookish Dodds.

But in 1983, in All-Star Squadron #18, writer Roy Thomas penned the character’s death. Donning the Sandman’s distinctive gas mask and fedora in order to shake out Nazi spies, Dian Belmont has a fatal collision into a lamp post when the tyre of the roadster is shot out by a saboteur.

A special mention goes to the mind-controlled limousine appearing in Thriller (DC Comics) The highly under-rated science fiction (not superhero) comic series, which we have previously reviewed https://worldcomicbookreview.com/index.php/2016/03/17/burn-the-oracle/, features the physically-infirm son of the President of the United States using mental commands to drive his limousine about.

Why so few? The portrayal of movement so necessary to convey action in comic book panels – the blurs and movement lines – can be easily rendered in the movement of a car. Superheroes use other modes of transport: DC Comics’ Wonder Woman (sometimes) has her invisible plane, and Marvel Comics’ Ghost Rider has a demonic motorcycle with flaming tyres.

But for the most part, as Gerry Conway noted in respect of the Spidermobile, superheroes on the move are more mobile or faster than cars, usually through flight or smaller and more nimble vehicles. Neither the flying superheroes Superman nor Thor will never need a car. (Indeed, the most iconic superhero comic book cover ever features Superman destroying a car.)

Marvel Comics’ two headline heroes, Captain America and Wolverine, are much more likely to appear on utilitarian motorcycles.

And advanced civilisations on other worlds, depicted often as the stage for adventure in superhero comics, do not usually use ground vehicles. Alien technology has evolved for the most part to rely instead upon flying machines of various descriptions. A avid reader of the genre would have formed the view that the use of cars is limited to primitive societies who allow their slow, wheeled vehicles to become gridlocked on the ground.

It seems a shame. Part of the James Bond mythos, in comics, motions pictures and books, involves the British super spy relying upon a range of exotic cars. The insanely popular motion picture franchise The Fast and the Furious is a showcase of speeding automobiles linked by a succession of flimsy plots. The dystopian Mad Max always involves a chases involving bizarrely-enhanced cars and trucks. Why we do not see many more cars on the centre stage of superhero comic books is a mystery.