DC Comics, July 2019

Writer: Geoff Johns

Artists: Gary Frank and Brad Anderson

Purchased: Quality Comics, Perth

Alan Moore’s the dimly-lit superhero dystopia of the 1986 comic book series Watchmen features a character called Dr Manhattan. Manhattan is a godlike creature, impassive and devoid of humour, bald and physically imposing, who looks down on humanity from a very great height. Who on (our) earth could this remind DC Comics’ Chief Creative Officer Geoff Johns of?

Mr Johns, wearing his writer’s hat, continues what on the face of it is a surprisingly clever reassessment of the continuity of one of America’s largest comic book publishers, DC Comics. Mr Johns, as we have previously discussed, seeks to amalgamate Watchmen into the brighter and more colourful landscape of DC Comics’ world famous superheroes, which includes Batman, Wonder Woman, The Flash, Green Lantern, and above all, Superman – “a dark fusion of Johns’ continuity porn and Moore’s meta-text” notes https://geekdad.com/2019/05/review-doomsday-clock-10-who-is-carver-coleman/ Ray Goldfield of GeekDad.com – an amusing but brutal assessment.

Exploring the Deep

The plot has three and, if we are right, four depths:

1. the shallowest level is the intrigue of the superheroes as they engage in their usual game of checkers: fisticuffs and energy blasts in a win-or-lose game, a token death by sniper rifle of an obscure villain, coupled with some standard revisionist history of the origins of some of the superheroes – notably the nuclear-powered Firestorm as a government initiative to infiltrate the superhero community. There is little of this action- driven plot line in this particular issue.

2. The story of Nathanial Dusk, a movie series starring an actor named Carver Coleman, is a strange tide within the text, made more curious by the fact that Nathanial Dusk is an obscure noir detective comic book published by DC Comics during the 1980s. The movie is, curiously, a work of fiction contained within a work of fiction – much like The Black Freighter vignette in Watchmen. In this issue of Doomsday Clock, we see Coleman’s beginnings as a young boy from a bad family, and follow his life all the way through to his bloody murder in 1954. (Like the rest of this comic, artist Gary Frank’s clean lines and attention to detail in this vignette is critical to communicating the story, and some of his drawings of Hedy Lamar capture the stunning beauty of the actress. Colourist Brad Anderson does more than pull his weight – Coleman’s last motion picture is rendered by Mr Anderson in monochrome.) The story’s antagonist, Dr Manhattan, is Coleman’s guardian angel – but only to an extent. The two meet every year in a cafe near the site of the young Coleman’s assault by Hollywood police on 18 April 1938 (the date of publication of Action Comics #1, Superman’s first appearance). Manhattan, who does not perceive existence within a linear time frame, tells Coleman what portends. When this leads to a stellar career and financial success, Coleman is at first excited and grateful, and as time progresses self-assuredly effervescent and cavalier. But when Manhattan tells Coleman that there won’t be a meeting next year, Coleman is beside himself with despair over the inevitable. Coleman’s subsequent murder and Manhattan’s passive witnessing of it is a device to underscore both Manhattan’s detachment from humanity and his non-linear perception of time.

3. Perhaps the deepest level of the story, and one we have only glimpsed so far during this series, concerns Manhattan’s explorations of the decades of DC Comics’ publishing history. DC Comics periodically adjust its continuity so as to make its characters more contemporary and to prune convoluted or contradictory plot lines. As explored in this issue, the first iteration of Superman involved the character arriving on Earth and first appearing in costume in 1939. As DC Comics injected vitality into the character and his peers, Superman’s arrival on Earth was pushed forward, to 1956, and then again to 1986.

Manhattan can perceive these repeated changes to continuity, and indeed meddles with them. Before acquiring his powerful magic ring, the original version of Green Lantern was caught in a train accident in 1937: in a bleak investigation into the malleability of this new universe, Manhattan causes the character not to survive. This is what reviewer William Evans of Black Nerd Problems observes https://blacknerdproblems.com/doomsday-clock-10-review/ with insight is “controlled experimentation” by Manhattan, a former scientist. Time and time again, just like the editors and writers of DC Comics such as Gardner Fox, Dick Giordano, Marv Wolfman, Dan Jurgens, and Mr Johns himself (“Even as the issue ventures into meta-textual commentary about the nature of DC Comics’ continuous state of revision, Johns revisits his own storytelling history within the publisher’s library”, notes https://www.cbr.com/review-doomsday-clock-10/ Sam Stone of CBR.com) Manhattan interferes with the appearances of superhuman characters. Yet Superman constantly reappears.

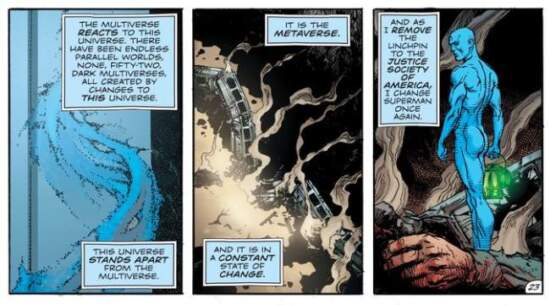

Manhattan forms the view that DC Comics’ fictional universe is actually:

1. defending itself against Manhattan’s systemic interference. We have seen something like this before: writer Warren Ellis has built storylines in comics in which super powered characters unconsciously operate as an autoimmune defence system against planetary threats (see for example The Authority in 1999, and Planetary in 2000-2007 for DC Comics’ imprint, Wildstorm Comics). Manhattan passingly notes the involvement of other cosmic threats – the Anti-Monitor from 1987’s series Crisis on Infinite Earths written by Marv Wolfman, and Extant from 1994’s Zero Hour written Dan Jurgens. (These events tend to be badged as a “Crisis”.) “In an extremely meta and relevant discussion, it crosses the gap between fictional story and editorial reality, debating that, no matter how much iconic characters and notions are meddled with… they fight back. Literally, within the story, but using their influence, gravitas, and social importance beyond it,” notes http://www.multiversitycomics.com/reviews/doomsday-clock-10/ Gustavo S Lodi of Multiversity Comics.

The Anti-Monitor and Extant seem to be other infections which were overcome, and Superman appears to be the most potent white blood cell.

Manhattan perceives an event in the immediate future where an enraged Superman attacks Manhattan, fist raised and eyes burning, beyond which there is nothing but blackness. Manhattan is left with one of two conclusions: is this a result of Manhattan ending the universe, or because Superman kills Manhattan? Does a virus finally kill its host, or does the autoimmune system of the host kill the virus?

2. a

“metaverse”. The mainstream continuity universe has rippled effects upon the

surrounding multiverse. Brian Michael Bendis touched upon this recently in DC

Comics’ Young Justice #1 (which we reviewed), when a character notes

that the magical dimension of Gemworld is repeatedly knocked about when DC

Comics’ primary universe – historically called “Earth – One” gets knocked about

by the latest reality-shaping Crisis. What Manhattan can not perceive, but what

other characters in the past, notably the superhero Animal-Man in the

character’s comic book series of 2001, is that the metaverse is repeatedly

redesigned by DC Comics’s staff writers and editors. Perhaps there is still

time for this fourth wall breaking to occur, although it would require much

finesse from Mr Johns. Still, Mr Johns has shown skill and subtlety thus

far.

The Fourth Wall

A diatribe on the nature of existence is beset with irony given DC Comics’

apparently precarious existence in its current state. Or is it really

incidental? Is this a fourth depth to the plot, a dimly perceived submarine

trench?

In March 2019, telecommunications giant AT&T successfully fended off a regulatory legal challenge in its acquisition of DC Comics’ parent company, Time Warner. Time Warner, now fused with Turner Communication and called Warner Media, includes very successful brands such as HBO and Warner Bros. DC Comics is apparently not of any real importance to AT&T. As reported in Forbes https://www.forbes.com/sites/robsalkowitz/2019/07/31/where-does-dc-fit-in-atts-vision-for-warnermedia/ , since the acquisition:

1. DC Comics’ once vaunted horror / alternative imprint Vertigo Comics has been shut down, as has its long-standing and enormously influential comedy title, MAD Magazine;

2. at the significant and enormous North American convention Comic-Con, DC Comics has been reduced from having its dominating centre stage pavilion to a strange Warner Media interactive booth in the corner;

3. AT&T’s chief executive John Stankey in an interview for Variety https://variety.com/2019/biz/features/john-stankey-warnermedia-ceo-hbo-warner-bros-1203281473/ discussed plans for each of Warner Media’s business divisions, the notable exception in that interview being that quirky publisher of comic books, DC Comics.

The Variety interview is fascinating. Mr Stankey is described as an emotionless corporate fixer who does not relate to the creative types at Warner Media.

Mr Stankey of AT&T looks like Dr Manhattan. Strip away the Pantone 292 U, and add a business suit, and there is a resemblance.

Mr Stankey has conducted awkward and unpleasant meetings with the business divisions of his new kingdom, Warner Media. This would have included the senior staff of DC Comics, of which Mr Johns is an important player. Perhaps the meeting looked like this:

As reported https://www.theverge.com/2019/3/4/18250075/att-restructures-warnermedia-hbo-turner-streaming by Chris Welch in The Verge in March 2019, Mr Stankey has a very direct and one-dimensional view of business. Business is not about culture: it is about investment focus:

““At a time when we must shift our investment focus to develop more content for specific and demanding audiences on emerging platforms, we can’t sustain a model where we invest one dollar more than necessary in the administrative aspects of running our business,” Stankey said in a staff memo addressing the restructuring.”

IGN’s reviewer Jesse Schedeen calls https://au.ign.com/articles/2019/05/30/doomsday-clock-delivers-the-answers-we-crave-doomsday-clock-10-review Manhattan “clinically detached.” It appears that Mr Stankey, mostly interested in using the new acquisition to promote AT&T’s core business, is remote and disinterested in the creative culture of DC Comics.

“Are you an angel?” asks Coleman when Manhattan first leads Coleman into the diner. Manhattan has to pause and think about the question. “No,” he replies.

Doomsday Clock,

like Watchmen, is expressly a Brechtian meta story. Think of the

story as a series of layered spheres. Given both the impact upon DC Comics’

publishing history, and the portentous events occurring outside in reader could

be forgiven for thinking that the name of the series was deliberately chosen to

describe DC Comics’ future while it simultaneously rejigs its past.

If this theory is correct, is Mr Johns saying that the metaverse with Dr Manhattan is manifesting in our universe with the existential threat of Mr Stankey? Or is Mr Stankey, a human Crisis who causes fictional worlds to live and die by his very existence, just subject to a clever parody?

Manhattan is given the final line in this tenth issue, “To this universe of hope I have become the villain.” If we are correct, then a public vent about a new boss has never been so subtle.