Image Comics, September 2019

Writer: Chris Dingless

Artist: Matthew Roberts

Unless the memory of it is shoved in our faces, we tend to forget the salve with civilisation offers. Civilisation, opportunity, health, and social mobility are part of a journey, and in the context of colonialism, invariably had a nasty beginning. This comic looks at the beginning of that journey in North America, overlaid with a monster story – in fact, a succession of monster stories.

We are always surprised by how few reviews there are of this comic. We have reviewed previous volumes of Manifest Destiny back in 2016 https://worldcomicbookreview.com/2016/03/20/an-american-heart-of-darkness/ and again in 2018 https://worldcomicbookreview.com/2018/07/15/manifest-destiny-volumes-5-mnenophobia-and-chronophobia/ . Those volumes of the title had a substantive horror and even science fiction element to them. The monsters which the famous American explorers Lewis and Clark encounter on their way into the American hinterland of what was then a vast Louisiana apparently have originated from mysterious arches. These enormous structures are scattered along the Mississippi River and each come with their own distinct horror – spores from a malevolent and apparently sentient plant which turns animals to zombies, a bat which animates its dead victims, a giant frog which tears men to pieces, and a fog which causes murderous illusions. We have also witnessed fearsome buffalo minotaurs and a tribe of furry creatures from a Stone Age civilisation who apparently are from a binary star system and have come to Earth by way of an arch.

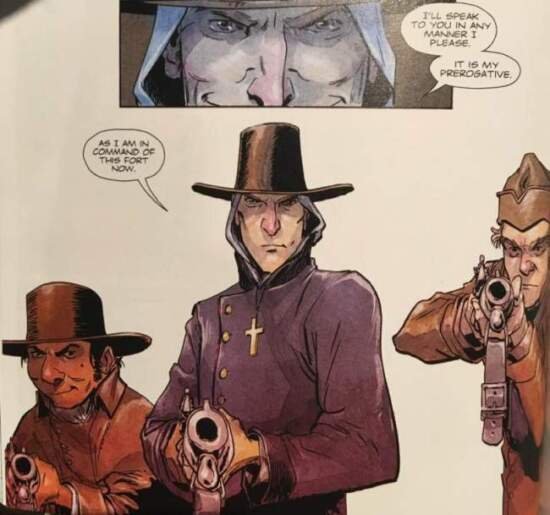

The arch which we see in this latest volume is the same one as in the last: an invisible structure which can only be seen when it is snowing. The expedition make camp for the winter. The story seems at first to have bumped back to a grim normality. It is an environment of terribly harsh, wintery conditions and tensions between a group of mostly men who have grown to distrust and dislike each other, accentuated by the religious preaching of a character named Sergeant Pryor’s, but are held together by Lewis’ harsh military discipline.

But beneath the surface is more unearthly trouble. Clark is haunted by the apparition of a sly conquistador named Maldonado. Clark, fearful of his sanity, refuses to acknowledge the conquistador’s existence. Lewis takes over the chores of the administration of the expedition when it becomes clear to Lewis that Clark, for good or bad, has retreated into himself. “I hate writing,” writes Lewis, twice, in Clark’s diary of the expedition.

The last volume of Manifest Destiny portrayed Maldonado as associated with, or some sort of herald to, a demon. The conquistador is strikingly rendered by artist Matthew Roberts. The rest of the characters in the story are tired, the inked lines of their faces and clothes communicating the weariness of the journey. But Maldonado is drawn as crisp. His face is cheerful and apple-cheeked and his ruffled collar is stiff and white. The different is stark. We have been, with respect, consistently impressed by Mr Roberts’ layouts and especially his visual character development. In the confines of a comic book, there should be only so many effective ways in which an artist can individually define a bunch of worn-out brown-garbed dirty men, and Mr Roberts knows them all.

Lewis and Clark suffer a mutiny lead by Pryor, and their way of dealing with this is as innovative as any other challenge suffered by the expedition during its horrific travels. The writer, Chris Dingless, seems to have a never-ending supply of methodological but out-of-the-box solutions to critical and sometimes lethal obstacles.

Mr Dingess’ true skill however is demonstrated when he invests one particular vile character with a small measure of sympathy. Corporal Hardy, a would-be rapist of a young Frenchwoman named Irene Lebrun, was strung up from a rope and used as bait to kill the amphibious beast which was picking the crew off. The price he paid was the loss of his leg. Murderously sullen, he reeked of vengeance. During this volume, other expedition members construct a prosthesis, and Hardy becomes mobile and helpful.

Lebrun is terrified by the prospect of being Hardy’s victim and brutally murders him. The manner of his death is sickening – he is reduced to a pulp. Hardy is a horrible would-be rapist, and there is no excusing that. But there was no suggestion in this volume that Hardy would have repeated his crime, and indeed having suffered a vicious punishment Hardy seemed willing to make amends. The environment is unforgiving and neither are the players in the drama.

There is an awful secret to the story which is starting to become apparent. It might be that the expedition’s leaders know precisely where they have been going after all, what they will find, and have come with the currency to effect a dark deal. The solution to the biggest problem, a problem of struggling colonialism – the manifest destiny of Europeans to conquer North America – seems to involve a shocking, hideous price. Messrs Dingless and Roberts paint a bleak, absorbing tale, one which we maintain ranks amongst the very best of Image Comics’ portfolio of publications.