Writer: Dan Hill

Artist: Gav Heryng

Mallet Productions Ltd, 2019

Post-traumatic stress disorder for military veterans is not confined to those with boots on the ground. The New York Times published on 13 June 2018 a harrowing story of a 29 year old drone operator’s struggle with PTSD:

At night, he dreamed that he could see — up close, in real time — innocent people being maimed and killed, their bodies dismembered, their faces contorted in agony. In one recurring dream, he was forced to sit in a chair and watch the violence. If he tried to avert his gaze, his head would be jerked back into place, so that he had to continue looking. “It was as though my brain was telling me: Here are the details that you missed out on,” he said. “Now watch them when you’re dreaming.” ….

[Another] operator executed a strike that killed a “terrorist facilitator” while sparing his child. Afterward, “the child walked back to the pieces of his father and began to place the pieces back into human shape,” to the horror of the operator.

The article can be found here: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/13/magazine/veterans-ptsd-drone-warrior-wounds.html

With this critique of independent comic book Disconnect, written by Dan Hill and with art by Gav Heryng, we start a new category of comics for the World Comic Book Review. The question of why we have not previously carved out a niche for this well-recognised sub-genre, war comics, is easy to answer: notwithstanding the militarisation of superhero comics, war comics have fallen out of favour with publishers and readers.

Over the years, themes of war comics have ranged from:

1. jingoistic patriotism (for example, most American comic books during the 1940s);

2. yearnings of battlefield glory (the United Kingdom’s very long running Commando); and

3. an unveiling of the horror and depression of war (Marvel Comics’ The Nam).

This first review of a war comic (actually, our second, if you count our brief review of Drones #1 https://www.worldcomicbookreview.com/2016/07/06/drones-1-review/ ), falls firmly into the last of those categories.

The protagonist, Kelly McLuhan, is a US veteran who flies a Predator drone over what could be any place in one of America’s many contemporary wars through Central Asia and the Middle East. Killing the enemy from the distance for Kelly is a task which is grimly fun, with the remoteness of a video game. Disconnect describes the air of nonchalant action in ridding the United States of foreign bad guys.

This echoes the New York Times article:

The sanitized language that public officials have used to describe drone strikes (“pinpoint,” “surgical”) has played into the perception that drones have turned warfare into a costless and bloodless exercise. Instead of risking more casualties, drones have fostered the alluring prospect that terrorism can be eliminated with the push of a button, a function performed by “joystick warriors” engaged in an activity as carefree and impersonal as a video game. Critics of the drone program have sometimes reinforced this impression. Philip Alston, the former United Nations special rapporteur on extrajudicial executions, warned in 2010 that remotely piloted aircraft could create a “PlayStation mentality to killing” that shears war of its moral gravity.

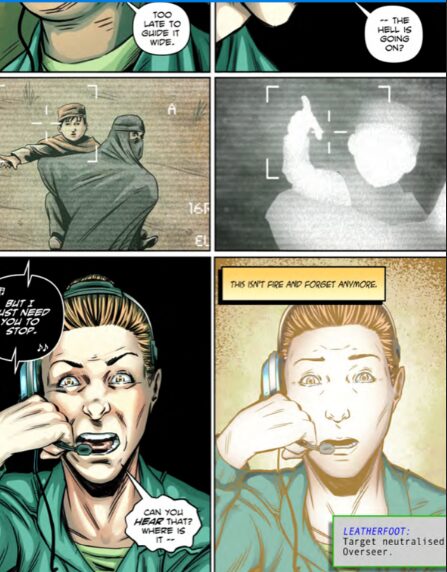

This facade comes tumbling down when Kelly realises she has accidentally launched a Hellfire missile strike on a mother carrying a boy. The Predator gives an infrared vantage. The boy, alive and radiating body heat, sees the missile approaching and points to the sky. And then he is gone in a white flash. It is an horrific and haunting scene, immaculately rendered by artist Gav Heryng.

Kelly suffers disturbed flashbacks to her accidental killing of the boy and her mother, which interfere in Kelly’s responsibilities as a mother and her interactions with her son. The staccato flickering of scenes by Mr Heryng is masterful (the frontispage and one of the narrative boxes uses the metaphor of a vinyl record, skipping and stuck):

The strobing effect of the art together with the subject matter is slightly sickening. We jolt backwards and forwards between the landscape of the drone strike and Kelly’s fumbling of mundane tasks such as a meeting with a school teacher, and going to the park.

These sorts of flickering existences are described in the New York Times’ article as common:

Drone warriors shuttle back and forth across such boundaries every day. When their shifts end, the airmen and women drive to their subdivisions alone, like clerks in an office park. One minute they are at war; the next they are at church or picking up their kids from school. A retired pilot, Jeff Bright, who served at Creech for five years, described the bewildering nature of the transition. “I’d literally just walked out on dropping bombs on the enemy, and 20 minutes later I’d get a text — can you pick up some milk on your way home?”

The situation is not helped by the cover story – that the boy might not have been a boy, but was probably just a dog. No one is fooled, least of all Kelly. Mr Hill’s repetition of the image of a “dog” is laden with subtext: official lies, excuses and justifications, the diminution of a little boy’s life to that of a stray dog.

By the end of the story, our protagonist gets her existential lurching under control by concentrating on what is most important to her in there here and now. Mr Hill confesses that but for a discussion with drone operator Brandon Bryant – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brandon_Bryant_(whistleblower) the story might have ended much more bleakly.

Disconnect is an important text in a world of high technology killing with impunity. As the New York Times article notes:

In conventional wars, soldiers fire at an enemy who has the capacity to fire back at them. They kill by putting their own lives at risk. What happens when the risks are entirely one-sided? Lawrence Wilkerson, a retired Army colonel and former chief of staff to Colin Powell, fears that remote warfare erodes “the warrior ethic,” which holds that combatants must assume some measure of reciprocal risk. “If you give the warrior, on one side or the other, complete immunity, and let him go on killing, he’s a murderer,” he said. “Because you’re killing people not only that you’re not necessarily sure are trying to kill you — you’re killing them with absolute impunity.”

Humans are fundamentally moral creatures. Impunity comes at a cost. Disconnect details that cost with stark and harrowing precision.

Disconnect is available on Comixology- https://m.comixology.co.uk/Disconnect/digital-comic/812956?ref=c2VhcmNoL2luZGV4L2Rlc2t0b3Avc2xpZGVyTGlzdC9pdGVtU2xpZGVy Mr Hill promises two more war comics in his series. We look forward to them, but with great trepidation.