Jean-Marc Rochette and Olivier Bocquet

Self Made Hero, June 2020

The copy for this autobiographical comic from the Amazon website reads as follows:

At sixteen, bivouacked on a mountainside beneath a sky filled with stars, Jean-Marc Rochette has already begun measuring himself against some of Europe’s highest peaks. The Aiguille Dibona, the Coup de Saber, La Meije: the summits of the Massif des Écrins, to which he escapes as a teenager, spark both exhilaration and fear. At times, they are a playground for adventure. At others, they are a battlefield. The young climber is acutely aware that death lurks in the frozen corridors of the French Alps. In Altitude, Jean-Marc Rochette tells the story of his formative years, as a climber and as an artist. Part coming-of-age story, part love letter to the Alps, this autobiographical graphic novel captures the thrill and the terror invoked by high mountains, and considers one man’s obsession with getting to the top of them.

For those of us with little or no interest in mountaineering, the story starts fairly slowly. Mr Rochette describes himself as having a tetchy childhood, dealing with his distant and cold mother and the tyranny of a boarding school. Mr Rochette’s father was a doctor who died in Algeria, and the man’s absence seems palpable. Mr Rochette is introduced to mountain climbing by his effervescent friend Sempre, and their very first climb is surprisingly treacherous for two young teens. School interferes in Mr Rochette’s increasing passion for both the sport, and also art, and he rebels in very amusing ways. Mr Rochette has some commercial success as a comic book artist, published in Actuel, the famous French underground magazine of the 1970s. But it is, initially, a coming of age story set in France without much more than that.

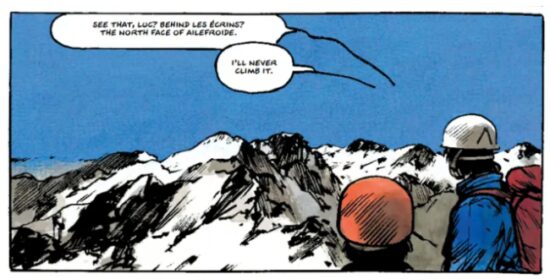

It would be a terrible mistake to give up your ascent at an early stage of this comic. (Our apologies for this mountaineering metaphor – we promise it is the only one.) Somehow, within the first half of the comic, a reader becomes engrossed in the personalities not just of the climbers but of the climbs. Each is described by their location, height, the names of the first climbers and year that they were climbed (most of them within the last century, which seems surprising), the material constitution of the climb, and the degree of difficulty. For the stranger to mountaineering, they are always, sometimes hilariously, described as “recommended” – is there not some horrifically pointed and lethal climb which is not “recommended”?

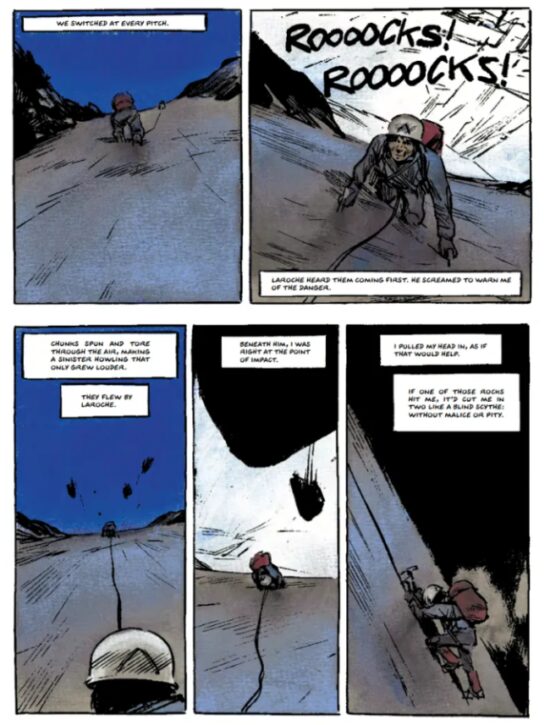

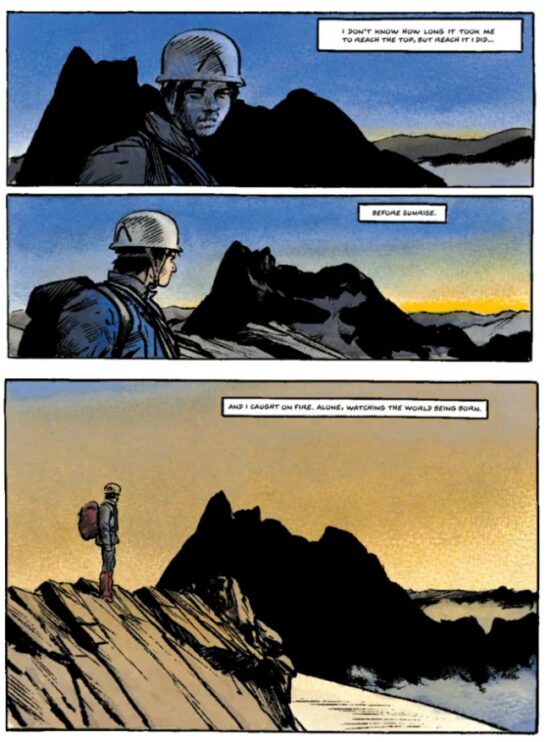

Each one of the climbs comes with its own techniques and strategies. Mr Rochette does not fall into the traps of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick by spending too much time on the miniatue of climbing. Instead, he uses text and, when appropriate, the complete absence of text to describe the peaks which Mr Rochette and his comrades climb, and the endless views they enjoy at the summit.

It becomes engrossing. Some of the climbs are simply insane.

Even Mr Rochette and Sempre realise that some climbs should not be attempted. In one scene, a German duo endeavour a dangerous climb. Mr Rochette and Sempre are manning a climbing station as part of their experience to qualify as guides, and Mr Rochette gets the Germans too drunk to climb, in order to save their lives.

Towards the end of the story, it becomes slowly apparent that the sport picks away at its participants. The star of Mr Rochette’s generation, Zartatan, is killed in an avalanche. A mother approaches Mr Rochette asking after her son who has been missing for three days, and Mr Rochette lies to her, telling her that he probably ascended in the wrong valley, but knowing that the boy is almost certainly dead. It is a devastating scene. The lovable Sempe himself gives up climbing, and is killed by the mountains nonetheless (albeit skiing).

We wait somewhat breathlessly for Mr Rochette’s fate, knowing that he wrote the title and it is autobiographical, but where does his journey lead us? And then, an ascent with the ridiculously buoyant Chardin. The pair must clean their cleats with an ice axe with every step. “Not every other step. Every step. Chardin skipped a step.” And Chardin falls in a textless panel, the blue sky behind him, into nothing. As comic book art goes, this quiet terror is perfectly captured:

Mr Rochette survives the climb and finds himself rattled. He starts small solo climbs in an effort to recover his nerve. Disaster strikes. We are not spared the gore, the cloud of blood in the air, the travel to the hospital, the operations, and poignancy of Mr Rochette’s fellow patients.

Mr Rochette goes on beyond climbing to write Snowpiercer, a science fiction comic book which was made into a movie (see https://www.worldcomicbookreview.com/2020/06/08/snowpiercer-the-prequel-part-one-extinction/ for Mr Rochette’s recent work on this). He has a complicated relationship with the mountains. The feeling of triumph and reliance upon skill and athleticism seems spiritual and Promethean. The comraderie of the climbers is entirely engaging – as a climber, you trust your life to the concentration and experience of your companion. But the mountains bring death and horror. Mr Rochette describes and repeatedly draws a singular gaping “yaw”, a devouring beast which will offer no mercy.

Mr Rochette cannot forget the brutality even as he yearns for it.

This is an excellent comic book, gripping and quite literally hair-raising. Altitude is available on Amazon – https://www.amazon.com.au/Altitude-Olivier-Bocquet/dp/1910593818