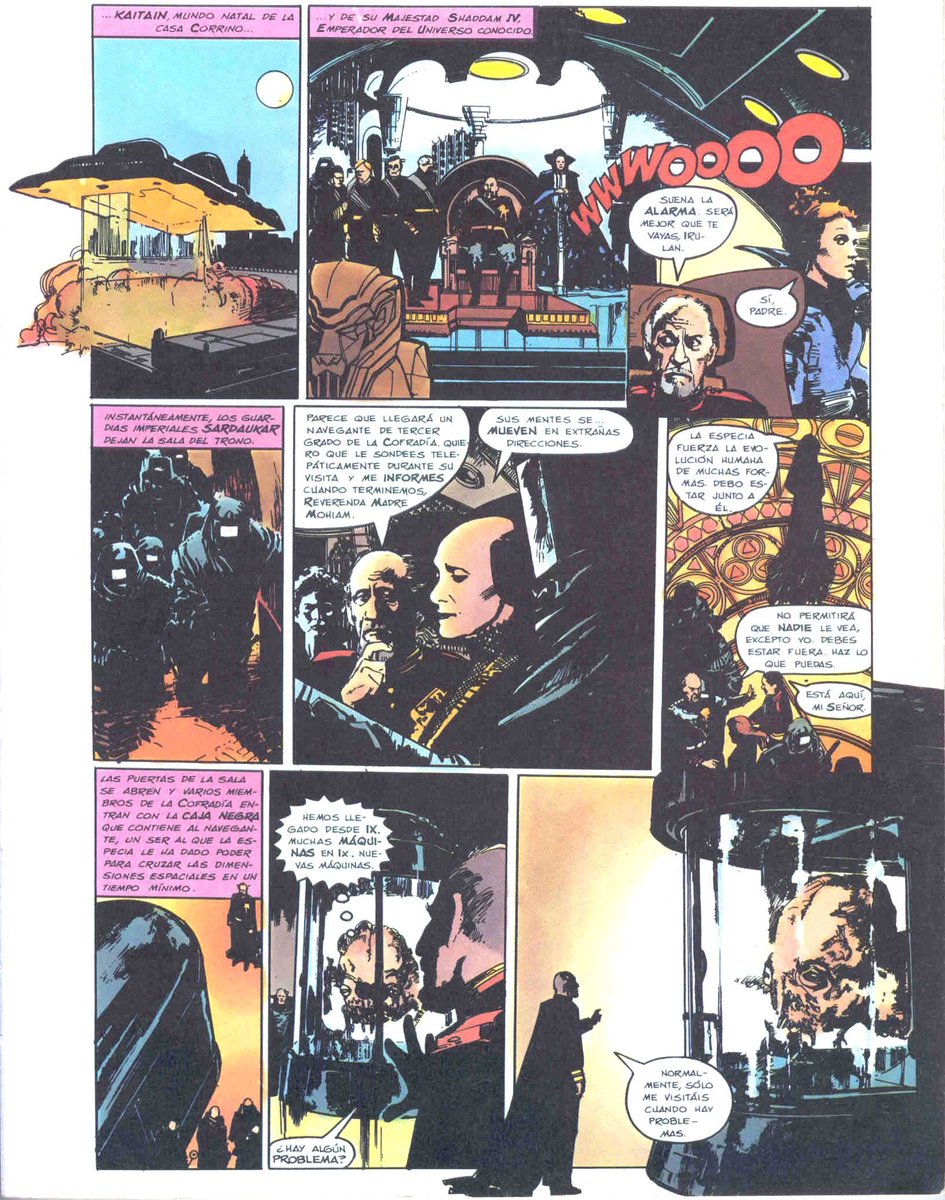

Writer: Ralph Macchio

Art: Bill Sienkiewicz

Marvel Comics, 1984

There has been some genuine excitement about the trailer for the forthcoming motion picture, Dune. This forthcoming motion picture is however only the latest effort to convert the late Frank Herbert’s classic 1968 book into a movie. The first effort is somewhat notorious. It was produced in 1985, and was directed by the otherwise masterful David Lynch. It is generally recognised as not being very good. (The 2021 movie, on the other hand, looks from the trailer to be very good.)

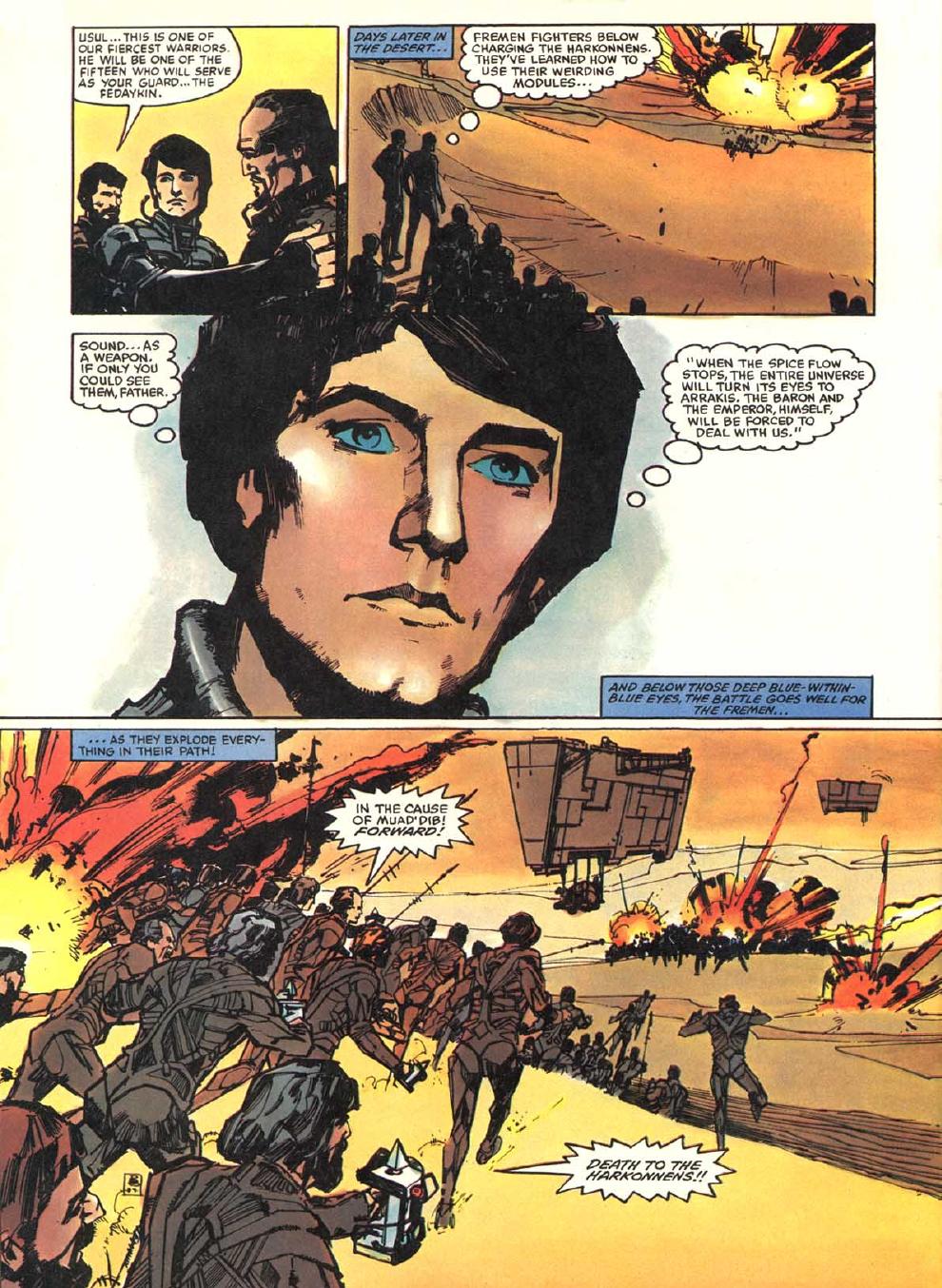

US comic book publisher Marvel Comics were commissioned to issue a comic book adaption of the movie (called “Marvel Super Special #36″). Bill Sienkiewicz is the artist, and his art is the best part of the comic. While some of the characters are clear portraits (Kyle MacLaughlin as protagonist Paul Atriedes and musician Sting as Feyd Harkonnen), Mr Sienkiewicz does his best with both the darker scenes of sinister plotting, and the tripper moments of the story.

It is important to note that the adoption was of the movie, not the book, and so the movie’s plot departures are on full display. Given the major task of the film maker is to make an extremely complex novel into a motion picture, it is hard to say why there were extraneous, complicated departures. Some of them are obvious. Baron Harkonnen’s death is not on a floor, his blood gushing from his neck, at the hands of Alia Atriedes: instead, the visual excitement of the antagonist flying out of control into the viciously toothed mouth of a giant sand worm was apparently too much to resist. Similarly, the “heart plug,” which the Harkonnens install upon their slaves, never seen in the novel, seems to be a more palatable way of demonstrating to a cinema audience the horror of the Harkonnens than the rape of drugged boys suggested by Mr Herbert.

But some are not – the “weirding boxes” which power a destructive sound generated by those trained in the ways of the Bene Gesserit are unnecessary. And some are just weird. Chief amongst these departures is that the captured Atreides mentat Thufir Hawat must milk a cat for the antidote to his poison. It is not meant to be a comic moment – it is supposed to suggest the Harkonnens’ perversity – but Mr Sienkiewicz draws the disturbed feline as decidedly unhappy with Hawat’s advances, and it draws a wry laugh.

Perhaps the greatest mistake of the movie and the comic was to portray the Atriedes, and particularly Paul Atriedes, as the good guys. The Atriedes were a feudal house. In his arrival on Arrakis, in the novel, Duke Leto engages in gross displays of wealth involving splashing of precious water. And as Mahdi, Paul Atriedes triggers a holy war which (according to the Mr Herbert’s second novel, Dune Messiah) resulted in the deaths of billions. But here instead we have Paul as a superhero, mastering skills and overcoming adversity to finally, and completely contrary to the novel, make it rain on the desert planet.

As for the forthcoming motion picture, Boom! Comics have launched Dune: House Atreides #1, a twelve issue series. It is adapted and scripted by Frank Herbert’s son, Brian Herbert, and Kevin J. Anderson (best known perhaps for his Star Wars novels). Both co-wrote the 1999 prequel novel based on the senior Mr Herbert’s notes. The problem is that Brian Herbert’s and Mr Anderson’s additions to the canon of Dune are not very good. From the Al Jazeera website https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2020/10/11/paul-atreides-led-a-jihad-not-a-crusade-heres-why-that-matters/ Ali Karjoo-Ravary writes this masterful analysis of Dune:

The trailer’s use of “crusade” obscures the fact that the series is full of vocabularies of Islam, drawn from Arabic, Persian, and Turkish. Words like “Mahdi”, “Shai-Hulud”, “noukker”, and “ya hya chouhada” are commonly used throughout the story. To quote Herbert himself, from an unpublished 1978 interview with Tim O’Reilly, he used this vocabulary, partly derived from “colloquial Arabic”, to signal to the reader that they are “not here and now, but that something of here and now has been carried to that faraway place and time”. Language, he remarks, “is mind-shaping as well as used by mind”, mediating our experience of place and time. And he uses the language of Dune to show how, 20,000 years in the future, when all religion and language has fundamentally changed, there are still threads of continuity with the Arabic and Islam of our world because they are inextricable from humanity’s past, present, and future.

A quick look at Frank Herbert’s appendix to Dune, “the Religion of Dune”, reveals that of the “ten ancient teachings”, half are overtly Islamic. And outside of the religious realm, he filled the terminology of Dune’s universe with words related to Islamic sovereignty. The Emperors are called “Padishahs”, from Persian, their audience chamber is called the “selamlik”, Turkish for the Ottoman court’s reception hall and their troops have titles with Turco-Persian or Arabic roots, such as “Sardaukar”, “caid”, and “bashar”. Herbert’s future is one where “Islam” is not a separate unchanging element belonging to the past, but a part of the future universe at every level….

… In Dune, Paul must drink the “water of life”, to enter (to quote Dune) the “alam al-mithal, the world of similitudes, the metaphysical realm where all physical limitations are removed,” and unlock a part of his consciousness to become the Mahdi, the messianic figure who will guide the jihad. The language of every aspect of this process is the technical language of Sufism.

The late Mr Herbert’s novels (and in particular the original) were sophisticated and drew repeatedly upon Sufism. The younger Mr Herbert’s and Mr Anderson’s novels were, well, more Star Wars novels. But to be fair, this 1984 comic is also quite obviously a Star Wars story – set on a desert planet (Dune is a sibling of Star Wars‘ Tatooine), and Paul Atriedes sometimes resembles Luke Skywalker.

As a postscript to this review, one of the more startling aspects of the comic is the use of now-dated thought balloons. Long replaced by internal narrative boxes, the thought balloons help the unfamiliar reader to understand the story, and remove some of the chaos which plagued comprehension of the 1984 movie. In that regard, together with Mr Sienkiewicz’s heroic efforts on art, this comic is one of those rare examples where the comic book adaption of the movie is better than the movie.