Writer: Tom King

Artist: Jorge Fornés

DC Comics, October 2020

October 13th of this year saw the release of Rorschach #1, the latest in a series of comics based on Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ seminar work Watchmen. This book is remarkable, however, in that it is not part of an event like American publisher DC Comics’ previous mediocre attempts at expanding the Watchmen universe were – although, interestingly, it apparently does take place in the same universe as the HBO Watchmen series that premiered last year.

As this topic has already been covered to great length on our website, I will not discuss the morality of writing comics based on Watchmen. The character of Walter Kovacs, also known as Rorschach, does need a bit of an introduction. It is not only one of the most prominent characters in the book, it is also the most controversial and misunderstood one. In the original Watchmen comic, Rorschach was depicted as a mentally damaged, justice-obsessed, bigoted objectivist created as a parody of classic superhero artist and creator Steve Ditko’s Randian heroes Mr. A and The Question. Rorschach’s inability to compromise even in the face of certain death ultimately caused his demise. Rorschach existed as a cautionary tale about comic-book vigilantes and their obsession with justice, criticizing the black-and-white morality of these characters by being, essentially, a morally grey anti-hero.

Alan Moore, co-creator of the character, has in an interview said this about Rorschach:

“I wanted to kind of make [Rorschach] like, ‘Yeah, this is what Batman would be in the real world’. But I had forgotten that actually to a lot of comic fans, that smelling, not having a girlfriend—these are actually kind of heroic! So actually, sort of, Rorschach became the most popular character in Watchmen. I meant him to be a bad example. But I have people come up to me in the street saying, “I am Rorschach! That is my story!’ And I’ll be thinking: ‘Yeah, great, can you just keep away from me, never come anywhere near me again as long as I live’?”

From then on, the character’s popularity has grown, and perhaps for all the wrong reasons. The film version of Watchmen by director Zack Snyder depicted him as a much more heroic character, stripping him of his most glaring issues and framing him not as a mumbling psychopath, but as a considerably more appealing Punisher-type character that dies a tragic, meaningful death. The otherwise forgettable Before Watchmen prequel focused on the character seemed to follow on Mr Snyder’s steps by glorifying his most violent actions while attempting to make him more sympathetic, which is not bad in and of itself but it does raise some questions about whether or not the creative team understood what the character stood for in the original book.

Doomsday Clock does not feature the original Rorschach, as Geoff Johns decided to (thankfully) not bring the character back from the dead. Instead, the Rorschach in Doomsday Clock is a young black man that is trying to follow on the footsteps of the original Rorschach. While this sounds like a promising set-up for such an interesting subversion or deconstruction of Kovacs’ legacy, Mr Johns completely missed the mark by having the new character cut ties with the original Rorschach not because he was a dangerous, blood-thirsty bigot, but because he indirectly caused his parents’ divorce. This was disappointing and generic to say the least. Perhaps the only version of the character that retains the essence of his original depiction is, ironically, the one where there is not a single character called Rorschach. The HBO show brings Rorschach’s legacy back in the form of the 7th Kavalry, an alt-right terrorist group that uses Rorschach’s notorious journal (a narrative vehicle in the Moore and Gibbons’ text) as a sort of creed – although admittedly the members of the group do take his quotes out of context to make them fit their agenda better, something that is known to happen in real life with alt-right conspiracy theorists (see for example the infamous QAnon).

The character’s political beliefs and their depiction through all of his different incarnations are extremely important because Tom King, writer of the book I will (finally) review, both acknowledges the character’s political history and takes a radically different path. These statements may sound contradictory at first, but we will get to that.

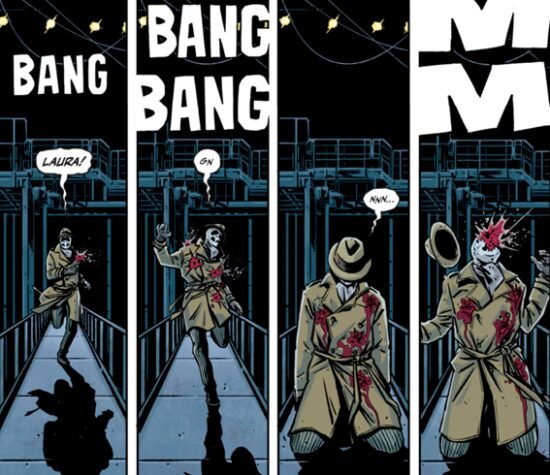

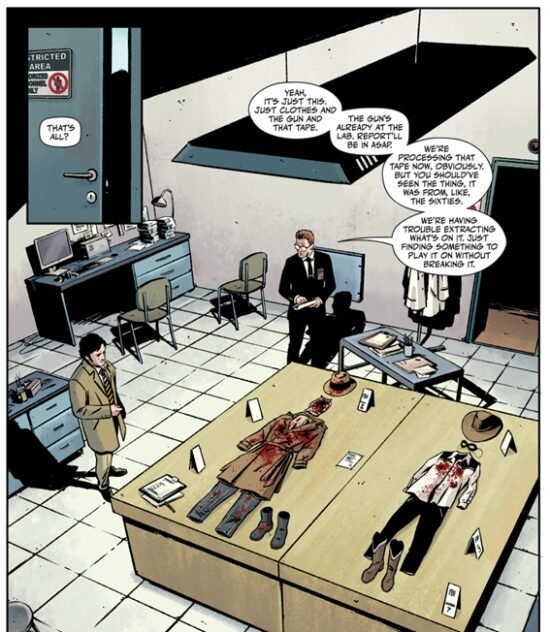

The book opens in medias res, with the death of a character wearing a Rorschach costume. We soon learn that this character has attempted to assassinate the conservative presidential candidate running against Robert Redford, and that both him and his partner were shot dead before they could perform the assassination. We follow the steps of an investigator trying to determinate the new Rorschach’s identity. Facial recognition is out of the question.

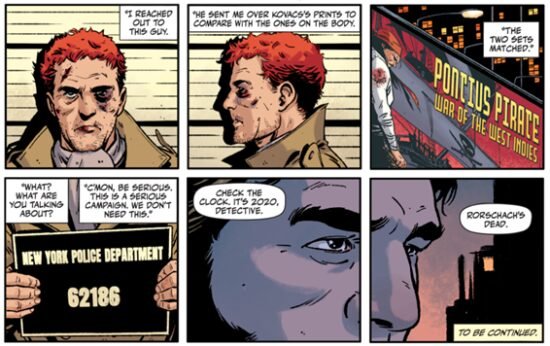

During the course of the story, the investigator finds out the attempted assassination was most likely performed by William Myerson, a former comic-book artist that created a popular pirate character in the 60s. It is important to understand that, in the world of Watchmen, pirates occupy the same cultural spot superheroes do in our reality, as the appearance of real-life heroes pushed comic-book publishers towards pirate stories instead. This detail, along with a few more sprinkled through the issue, makes it kind of obvious that William Myerson is this world’s equivalent to Steve Ditko.

Instead of being an objectivist, however, Myerson is described as the polar opposite. Myerson is a left-wing fanatic that never left his home once he stopped writing comics, and for most of the issue it is heavily hinted that this man is the new Rorschach, both by the characters and the implications of his beliefs. Tom King said in an interview with syfy that his Rorschach’s morality is not based on Ayn Rand’s beliefs but on her contemporary Hannah Arendt’s ideas.

“Instead of it being from an Ayn Rand background, I transitioned it just to sort of respond, and I made [the contemporary Rorschach] obsessed with Hannah Arendt, who is a different philosopher, Ayn Rand’s contemporary, another Jewish immigrant from Germany, but on the left, not on the right, who was obsessed with the concept of citizenship,” King explained. “She had been in a concentration camp, and how we as a free society stop another Nazi rising was sort of her obsessesion (sic) of her whole life. Instead of constructing Rorschach from a Randian point of view, if we construct him from an Arendt point of view, how does that change our conception of superheroes, and our conception of vigilantism? If we go from the idea of ‘it’s obviously bad to kill people without trials’ to ‘Is it bad to kill Nazis without trials?’ it makes a different moral universe and [asks] different moral questions, or at least the same questions but, you know, turning the ball on its side so you can see it from a different angle.”

Disappointing as it may be (and ignoring the fact that Hannah Arendt was married to a member of the Nazi party and was opposed to killing Nazis even with a trial), this means that Mr King has created a pseudo-leftist version of Rorschach in his attempt to “see the character from a different angle”, instead on deconstructing the original character’s cultural legacy. Perhaps he is planning on doing this still, but I can not help but feel a bit disappointed by his very simplistic take on the “both extremes are bad” mentality.

The issue ends with the revelation that the body’s fingerprints match those of the late Walter Kovacs. This is extremely confusing, more so after the whole issue’s obsession with Myerson and his political ideas. But this is Tom King. Mr King may very well slap us in the face with an actually subversive idea in the next few issues, or he may add yet another disappointing, centrist version of the character that brings nothing new to the table.

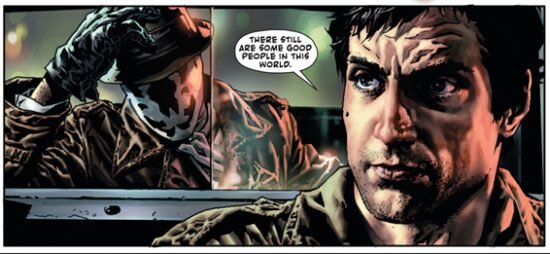

Looking on the bright side, Jorge Fornés art is no doubt the highlight of the issue. The Hispanic artist has stated before that he loves working on noir-style stories. Flawed as it is, Rorschach #1 is very much a noir murder mystery, with the small twist that it focuses on the attempted killer’s death, and not the target’s death. Mr Fornés’ version of Rorschach is probably my favourite in terms of visuals. As much as I love John Higgins’ colours from the original book, Fornés and colourist Dave Stewart (no relation to this website’s editor) offer a much more fitting gritty, but still clean and concise, look.

Regarding the visual style of the book, it is also a breath of fresh air that King and Fornés stay away from the 9-panel grid, which was heavily used in the original Watchmen. Instead of attempting to replicate Moore and Gibbons’ style, they’ve developed their own panel structures. This stays away from the faults of Doomsday Clock and its meaningless, meandering, de-compressed compositions. It opts instead for a much more concise, flexible and detail-focused visual narrative that leaves no room for unnecessary panels or text bubbles: it feels as if everything is there for a reason.

How does this title compare to that other recycling of Rorschach, entitled Before Watchmen: Rorschach? Published eight years ago, despite an all-start cast of writers, Before Watchmen is, in general, a very mediocre series of comic books. DC Comics’ idea for this project was to create eight prequels to Watchmen, each focusing on one of the main characters (and the minor villain Moloch, for some reason), and shining some light on their past.

It fails especially with Rorschach. There is not a whole lot to say about Rorschach at that point in the timeline. The character had his entire life story told in the original book, so the only option to create a compelling story was to somehow explore his identity within his own universe (or even within popular culture as a whole) in a way that had not been done before. If you must write a comic about Rorschach, you should at least try to do something new with him, especially considering how the Zack Snyder movie had recently brought the character back under the spotlight and a new wave of fans had risen to idolize him.

This is not what Before Watchmen: Rorschach does, however. In fact, I’m not sure exactly this book does, and I do not think its creators 9including acclaimed writer Brian Azzarello) did either. Let’s dive right in to understand why this book fails to justify its own existence in any meaningful way.

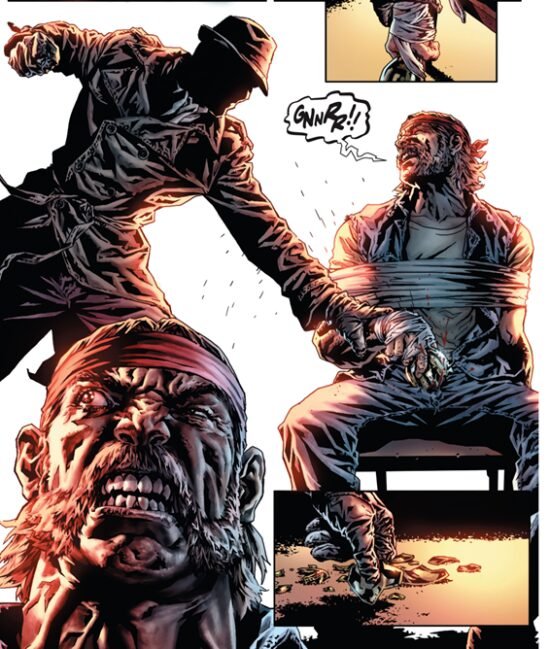

Let’s talk first about the art, which in and of itself is not a problem because Lee Bermejo is perfectly comfortable with the environments and characters he has to draw here; he’s known for his gritty, dark look and his attention to detail, which admittedly make this book a bit more bearable. My problem, however, is that he is far from the best choice in artist for a book about Rorschach, as his style tends to glorify violence, making every punch and kick look powerful and impactful. This is not, however, what the original Watchmen was going for with its more nuanced, realistic depiction of violence, and I cannot stop thinking that this version of Rorschach is more akin to the character we saw in the misguided movie adaptation (badass, imposing and powerful), than to the original.

As for the story, it suffers from a severe case of decompressed storytelling. This becomes obvious upon concluding the first issue and realizing that everything in it could have been told in half the pages. The panels are way too big and the text too scarce. It would not be a problem if this comic was trying to tell a more abstract, contemplative story. But here it only hurts the pacing of the almost non-existent story. Too much space that could serve a narrative or worldbuilding purpose is left completely empty for no discernible reason. This ties in with the comic’s necessity to depict violence in excruciating detail, leaving much less space to actually tell a compelling story.

This is a problem that many of Mr Azzarello and Mr Bermejo’s collaborations have. But they usually make up for it with spectacular moments and impressive visuals, and they have way more control over the story and can pace it in a completely different way. In this case, not only did they have little to no control over the creative direction of the miniseries (a vignette in an overall creative concept), they also had to work within the restrictive confines of the Watchmen canon.

There is very little to say about the plot itself, mostly because this book is more interested in depicting violence and pain than in telling a story, and it quickly devolves into Rorschach beating up criminals with a connective tissue as weak as the pacing. Rorschach was beaten up by a gang and goes around either exerting revenge on the ones who hurt him or interrogating them to get to their boss. The “B-plot”, if you want to call it that, is about a mysterious serial killer that targets women and writes messages on their bodies after killing them. The only way this ties in with Rorschach’s story is that the waitress of the Gunga Diner that was friendly towards him eventually gets targeted by the serial killer. If you do not see how that is related to everything else in the story, it is because it is not. The killer never ends up being relevant, he never interacts with Rorschach, and he gets caught off-screen after the woman survives and identifies him. The main plot ends when Rorschach uses a power outage in New York to infiltrate the gang’s headquarters. Rorschach gets caught fairly quickly, and what comes next is absolutely baffling in that it completely ignores the basics of character development and basic storytelling: the gang leader steals his mask, ties Rorschach to a bed so that his men can torture him and then leaves to fight crime with Rorschach’s mask on (for some unspecified reason) only to be killed almost immediately by a group of looters. Rorschach escapes by pure chance, doesn’t learn anything and does not even change as a person during this incident, as he is a passer-by in his own story.

The only thing that could be seen as character development is that he asks out the woman of the Gunga Diner halfway through the comic after she helps him out, although he forgets about her the minute the power outage starts, allowing the previously mentioned serial killer to capture her. Whatever this attempt at a love subplot is trying to imply against Rorschach becomes undermined by the fact that he is shown to be both extremely ungrateful and a misogynist before and after the events of this story. The notion that he would show this level of gratefulness to anyone, much less a woman, is completely ridiculous (it is important to remember that this takes place after the anti-masked vigilante legislation called the Keene Act, which means Rorschach is no longer working with his partner Nite Owl and has gone through the mental breakdown that turned him into a mad man).

Otherwise, this subplot ultimately goes nowhere, and looks like it was included in the comic just for the sake of it.

And speaking of seemingly random inclusions that end up amounting to nothing, this book has quite a few of them. One of the most notorious one is the transition from Rorschach using a typewriter to write his journal to doing it by hand, something that could have been interesting if it was motivated by something or had any consequences at all.

We also have the inconsequential and completely arbitrary choice to include Travis Bickle, the main character from the Martin Scorsese film Taxi Driver, in a sequence in which he talks to Rorschach about how he appreciates what masked vigilantes do. While I don’t doubt a person like Travis would be totally on board with what Rorschach and company are doing, the inclusion of this character is so random that it becomes distracting. If this was a book with more substance to it, a nod to a movie that probably inspired the overall aesthetics of Mr Bermejo’s art would’ve been a fun quirk. But in a story so devoid of literally anything in terms of themes, character development and subtext, it leaves readers scratching their heads.

Before Watchmen: Rorschach is exactly the type of book Alan Moore wanted to avoid when he first refused to write more Watchmen content for DC Comics: a soulless, uninteresting, completely non-challenging book that adds nothing to the Watchmen mythos and completely fails to justify its own existence beyond being one of many cash-grabs created by DC Comics to milk a few more dollars out of Moore and artist Dave Gibbons’ remarkable literary creation.

Neither should anyone be happy with this first issue of Rorschach. Perhaps this series will improve with time, as a few of Tom King’s works do, or perhaps it will not. Only time can tell, and until them I will be happy with looking at Jorge Fornés’ clean, smooth artwork.