Writer: Geoff Johns

Artist: Jason Fabok

DC Comics, August-October 2020

The concept that American superhero comic book publisher DC Comics’ most iconic villain, the Joker, could actually be three people was first touted in Justice League #49, in 2015. In that comic, Batman took the seat of the space god Metron and was shown the truth to any question: Batman learned that there was not one Joker, but three. It is a very new proposition. DC Comics have never sought to replicate or replace the character in the same way that the publisher does with its superheroes (all of its major superhero properties, without exception, have been substituted upon retirement or impermanent death at some stage).

It however goes some way to explaining the differences in characterisation of the madman over the years. But every franchise character is subject to interpretation and reinterpretation. So, was this necessary?

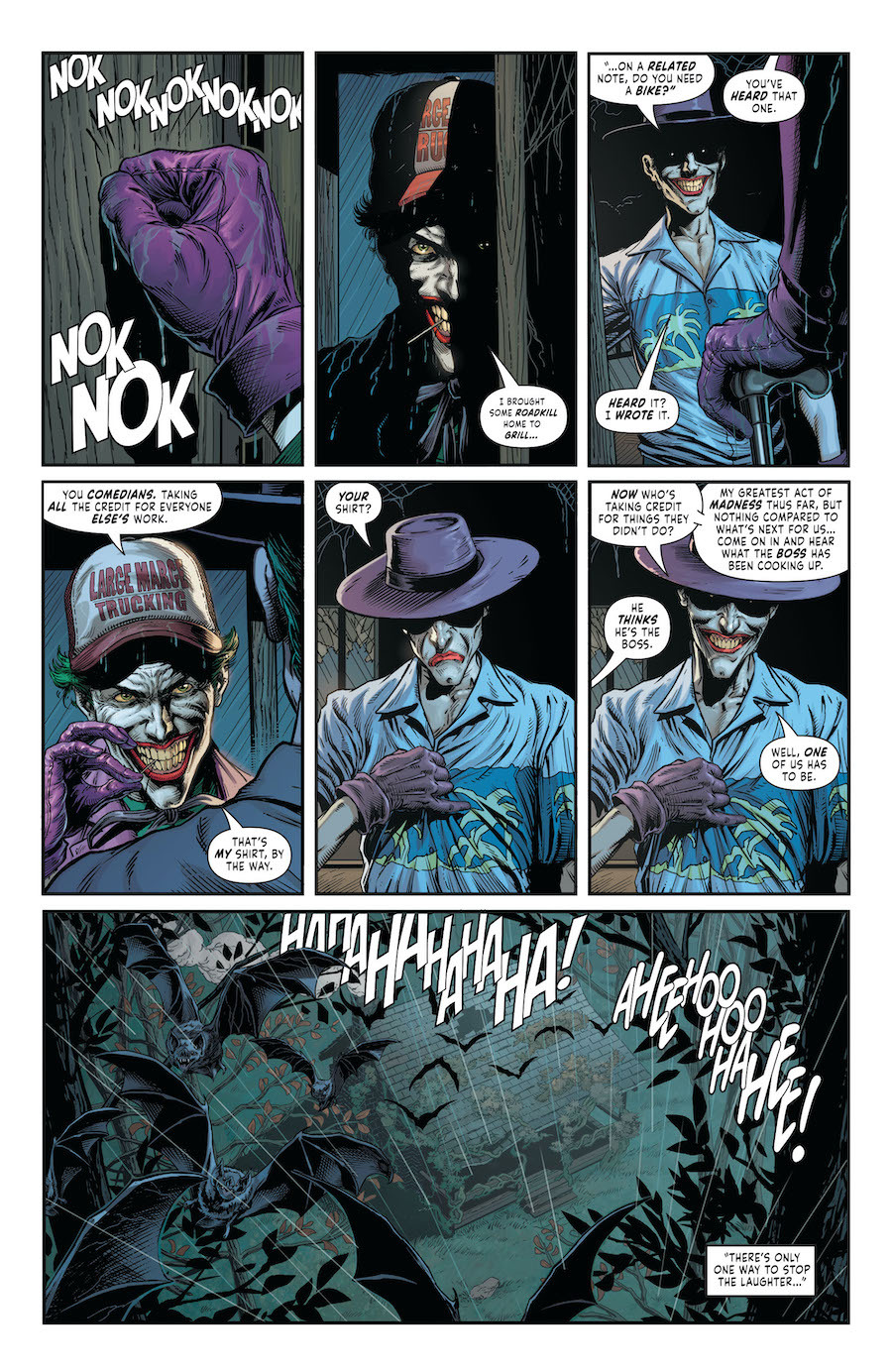

Writer (and DC Comics’ chief creative officer) Geoff Johns divides up the Joker into three manifestations. The first of these is “The Criminal” and apparently refers to the Joker’s very early origins as a thief and murderer, rather than a psychopath. This version is the one who is ostensibly in charge.

The second Joker is “The Clown”, and is the version of the Joker from the classic Batman story, “The Joker’s Five Way Revenge” (Batman #251, September 1971 ) by the late Denny O’Neal and Neal Adams. This story re-characterised the Joker as a crazed murderer and as Batman’s arch-nemesis. Online pop culture site Vulture discusses this evolutionary jump amidst an interview with Mr Adams.

At some point, our editor, Julie Schwartz, basically said, ‘You know, guys, we gotta bring in the clowns,’” Adams recalls. They were headed in a direction of realism when they were told they had to resurrect a historically goofy lineup of past Bat stories. “So what do you do with a Joker?” Adams remembers them asking themselves. “Well, we took a harder edge. We decided that Joker was just a little crazy.” Prior to that, Joker hadn’t really been given much in the way of motivation or nuance; he was just a guy who liked committing crimes in a silly fashion. O’Neil — who couldn’t be reached for comment — and Adams were the first to make the decision: Joker would be a homicidal, mentally unstable maniac. They didn’t explore his origin story, but they would suggest through his actions that there was something innately wrong with him that made him lethally dangerous.

With that, we have the etymology of the description of the Clown. The Clown perhaps is also the one who brutally killed Batman’s teen sidekick Robin in “A Death in the Family” (Batman #426-429, 1988). This version of Robin, Jason Todd, was much later reincarnated and uses the nom de plume the Red Hood. The scars from Todd’s skull collapsing under the blows from the Joker’s crowbar are evident in a panel in this title, drawn by the highly capable Jason Fabok.

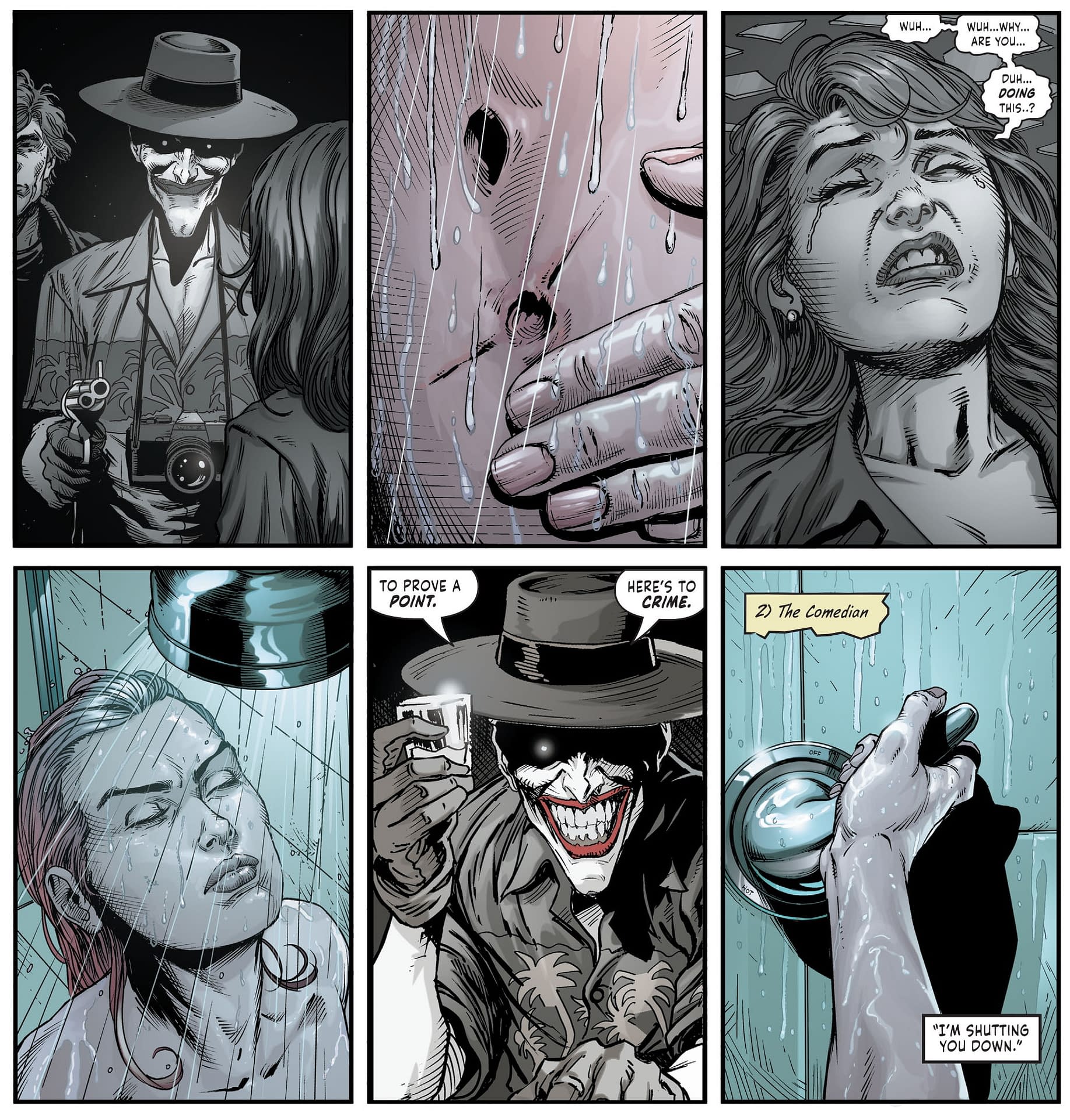

The third and final Joker is “the Comedian”. Mr Johns draws deeply upon Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s 1987 classic story, The Killing Joke. The Killing Joke features an origin of the Joker as a failing comedian who learns that his wife and unborn child were killed in an electrical accident involving a baby bottle heater. The point of that story is that, faced with despairing tragedy of the death of his family, Batman did not descend into madness. But the Joker did.

Notwithstanding the presence of the Criminal and the Clown, The Three Jokers is in essence a sequel to The Killing Joke. The Killing Joke is a masterful crime/horror story. But the fact that The Killing Joke has been absorbed into DC Comics’ mainstream continuity remains the subject of contention. As recently as 25 January 2021, writer Gail Simone, perhaps most famous for her work on DC Comics’ titles Birds of Prey (featuring the character Batgirl), complained on Twitter about the closing sequence in which Batman and the Joker together laugh. In that scene, the Joker has just crippled Barbara Gordon (Batgirl’s alter ego) and possibly raped her, and the captured police commissioner Jim Gordon is compelled to look at photographs of his daughter lying on the floor, going into shock, and bleeding out. Yet Batman and the Joker laugh along with each other in the last scene. Batgirl revisits the moment of her maiming in The Three Jokers.

It has been repeatedly denounced as an inappropriate conclusion to the carnage in the preceding pages. Scottish writer Grant Morrison has theorised that the closing scene has Batman killing the Joker https://io9.gizmodo.com/grant-morrison-says-alan-moore-secretly-killed-the-joke-1156091439, evidenced by the cessation of laughter, and Batman’s monologue earlier in the comic about how the two men are on the precipice of a final confrontation. Mr Moore himself has said the ending is to be interpreted otherwise https://www.inverse.com/article/14967-alan-moore-now-believes-the-killing-joke-was-melodramatic-not-interesting. It is a fascinating insight by the author:

I’ve never really liked my story in The Killing Joke. I think it put far too much melodramatic weight upon a character that was never designed to carry it. It was too nasty, it was too physically violent. There were some good things about it, but in terms of my writing, it’s not one of me favorite pieces. If, as I said, god forbid, I was ever writing a character like Batman again, I’d probably be setting it squarely in the kind of “smiley uncle period where Dick Sprang was drawing it, and where you had Ace the Bat-Hound and Bat-Mite, and the zebra Batman—when it was sillier. Because then, it was brimming with imagination and playful ideas. I don’t think that the world needs that many brooding psychopathic avengers. I don’t know that we need any. It was a disappointment to me, how Watchmen was absorbed into the mainstream. It had originally been meant as an indication of what people could do that was new. I’d originally thought that with works like Watchmen and Marvelman, I’d be able to say, “Look, this is what you can do with these stale old concepts. You can turn them on their heads. You can really wake them up. Don’t be so limited in your thinking. Use your imagination.” And, I was naively hoping that there’d be a rush of fresh and original work by people coming up with their own. But, as I said, it was meant to be something that would liberate comics. Instead, it became this massive stumbling block that comics can’t even really seem to get around to this day. They’ve lost a lot of their original innocence, and they can’t get that back. And, they’re stuck, it seems, in this kind of depressive ghetto of grimness and psychosis. I’m not too proud of being the author of that regrettable trend. As with all of the work which I do not own, I’m afraid that I have no interest in either the original book, or in the apparently forthcoming cartoon version which I heard about a week or two ago. I have asked for my name to be removed from it, and for any monies accruing from it to be sent to the artist, which is my standard position with all of this…material. Actually, with The Killing Joke, I have never really liked it much as a work – although I of course remember Brian Bolland’s art as being absolutely beautiful – simply because I thought it was far too violent and sexualised a treatment for a simplistic comic book character like Batman and a regrettable misstep on my part. So, Pradeep, I have no interest in Batman, and thus any influence I may have had upon current portrayals of the character is pretty much lost on me. And David, for the record, my intention at the end of that book was to have the two characters simply experiencing a brief moment of lucidity in their ongoing very weird and probably fatal relationship with each other, reaching a moment where they both perceive the hell that they are in, and can only laugh at their preposterous situation. A similar chuckle is shared by the doomed couple at the end of the remarkable Jim Thompson’s original novel, The Getaway.

And much more recently, for Deadline https://deadline.com/2020/10/alan-moore-rare-interview-watchmen-creator-the-show-superhero-movies-blighted-culture-1234594526/?fbclid=IwAR3f8Tvxnus6OD0C2aHUgP–QSHrY0AmjihQ9HT2taQq1RpOkYZfkt5EAGc Mr Moore agrees that the story was too violent:

I have no interest in superheroes, they were a thing that was invented in the late 1930s for children, and they are perfectly good as children’s entertainment. But if you try to make them for the adult world then I think it becomes kind of grotesque. I’ve been told the Joker film wouldn’t exist without my Joker story (1988’s Batman: The Killing Joke), but three months after I’d written that I was disowning it, it was far too violent – it was Batman for christ’s sake, it’s a guy dressed as a bat. Increasingly I think the best version of Batman was Adam West, which didn’t take it at all seriously.

Missing from the grouping of important iterations of the character is the Joker from Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, a version of the character set in the future. This Joker is depicted as being catatonic, until he sees on television that Batman has come out of retirement. With that, the Joker finds purpose and is depicted as vicious but strangely lucid. The character manages to murder David Letterman’s studio audience with his deadly Joker gas as he makes an escape, only to have his neck broken by Batman in a final struggle.

It is a violent story. The Dark Knight Returns, set in a grim future, portended the death of Jason Todd, and set the stage for A Death in the Family. Concepts which might, with the benefit of hindsight, be too violent for Alan Moore are the foundation stone for much of the modern superhero genre laid by Frank Miller. Mr Johns has no hesitation perpetuating them.

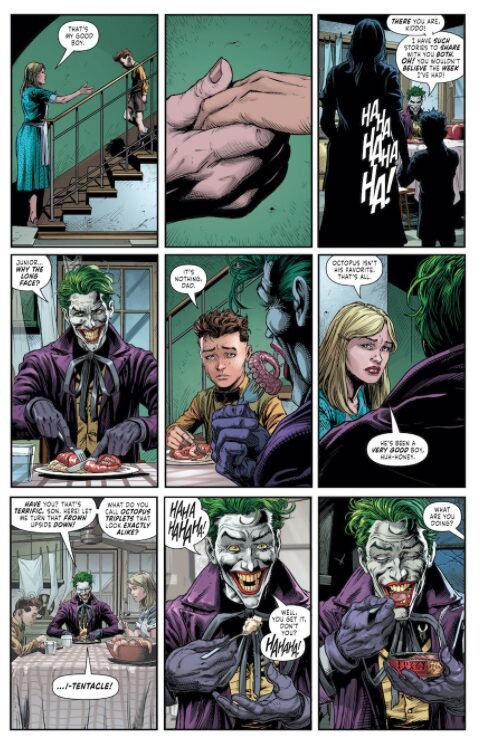

The twist to the story in The Three Jokers is that we were lead to believe from The Killing Joke that the Joker’s wife and new-born had died in an absurd electrical accident. Mr Johns has reworked that. The two actually ran away, helped by the police, and are hiding in Alaska. Batman knows this, but chose to keep the information to himself.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22007331/Screenshot_2020_11_01_at_11.51.52_PM.png)

It is clear that their apparent deaths weight upon the Joker at a deep emotional level, notwithstanding his psychosis. There is a delusional sequence, wonderfully done by Mr Johns and artist Jason Fabok in which The Joker sees himself coming home at the end of a working day to them: he acts out a dinner with a mannequin and torn teddy bear. Its a startling scene.

Mr Johns adds a new and almost poignant layer of characterisation to the villain. The Joker laments the loss of a family life he might have otherwise had – a perverse and improbable existence in which his wife and son live in a state of barely masked fear, but something taken from him by fate and which he wishes was otherwise.

What will it mean if the Joker finds out that his family are alive and that the Batman has kept this secret hidden from him? We expect that Mr Johns is setting up a new level of antagonism between the two characters.

The opportunity missed in this title was to render Jason Todd into a new Joker – or, at least, to have him scarred and bleached with acid like the Jokers but be able to deal with the transformation. Todd is described as taken on the identity of the Red Hood with a sense of irony: the Red Hood was the Joker’s first incarnation before his famous fall into the vat, and the Joker was the man who put Todd into a grave. Taking some piece of the Joker and making it his is interesting psychology.

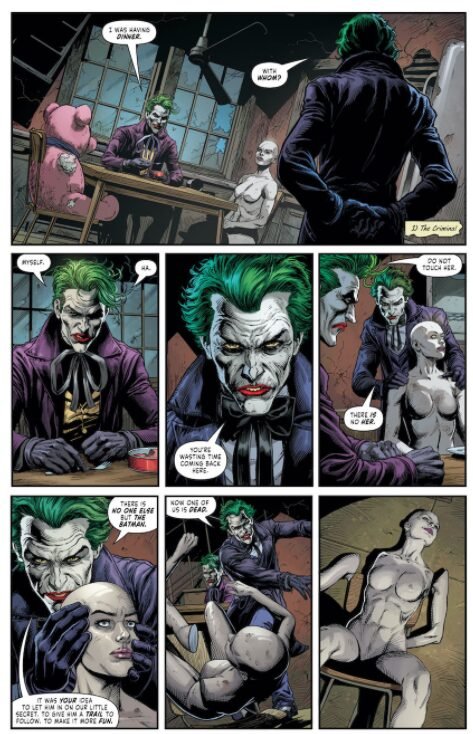

In this story, Todd is kidnapped by the three Jokers and, again, almost beaten to death.

Todd escapes, with the aid of Batman and Batgirl, and dramatically avenges his death by killing the clown version of the Joker. There is a terrible and chilling piece of dialogue, where it is revealed that Todd, as a boy and being beaten to death, offered to become the Joker’s Boy Wonder. The revelation, the return to humiliation and the subtext of sexual offering, prompts Todd to shoot the Joker in the head. Here, Alan Moore’s bête noire is in full and horrible flight.

The more daring plot that would have involved Todd being recruited as a Joker certainly looked for a while in the first issue like this would occur. There would have been some poetry to this. Killed by the Joker, and then reincarnated, Todd becomes first the Red Hood, and then becomes the man who killed him. But Mr Johns seems to have shied away from such a radical development.

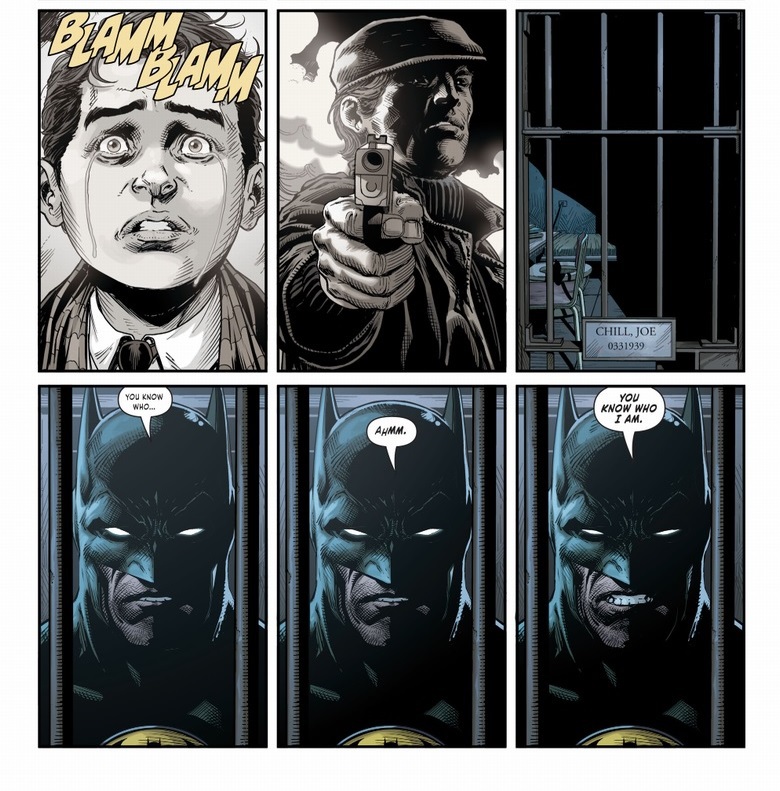

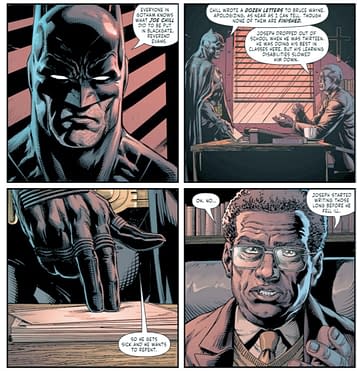

Unexpectedly, The Three Jokers is also a tale of forgiveness. A significant character development occurs with the seemingly immutable lead, Batman. Batman’s war on crime can never end – that would be an entirely uncommercial thing for DC Comics to do. But here, Mr Johns enables Batman to forgive the murderer of his parents. We have not seen this before. First, when Batman first speaks to Joe Chill in his cell, his voice is that of a little boy whose parents have been murdered:

Batman self-corrects, hardens his voice, bares his teeth, and narrows his eyes. He has to consciously assume the fearsome aspect of Batman. It is a fantastic insight: Batman, at the end of the day, is afraid of Chill.

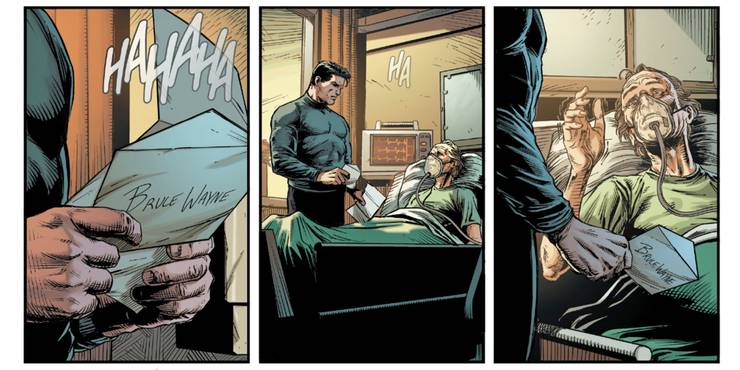

The reality of the murder, and his reason for the crusade on crime, then spins for Batman like a broken compass. Batman learns that Chill had been trying to express his guilt and regret for killing the Waynes for years. And Batman, as Bruce Wayne, is there to comfort Chill when Chill, an old sick man filled with remorse, finally passes away.

It is a moment which the superhero comic genre does not ordinarily allow, and especially not to the most grim and driven of them all, Batman. Batman giving comfort to the dying killer of his parents contrasts with the earlier actions of Todd: executing the Joker in cold blood was a merciless act of revenge. Batman shows he is much better than that. Contrition, compassion and forgiveness are cousins to compromise, something the driven crimefighter seemed, until now, incapable of. We do not generally quote the Bible in our reviews, but we are reminded of Ephesians 4:32: “Be kind and compassionate to one another, forgiving each other, just as in Christ God forgave you.” In Justice League #49, Batman possessed the powers of a God. Here, the character instead acts with humanity.

Alan Moore wrote excellent Batman stories, but he never wrote about Batman’s hidden fear and the potential for forgiveness. Put to the side the horror of the Jokers and the sordid experiments upon their many captives revealed in this title: for something so fundamental to such an important character to be revealed and to change, in an interaction invoking such a raw emotion response, makes The Three Jokers one of the best Batman stories ever written.