Writer: Christophe Bec

Artists: Eric Henninot, Milan Jovanovic

Humanoids, 2016

NATURE SOMETIMES ALLOWS HUGE CREATURES, though most are long gone. Whales, giant redwoods, big dodo birds, maybe soon the whole Amazon forest are recent casualties within memory alongside ancient extinctions like the dinosaurs 66 million years ago downed by nuclear winter following an asteroid impact in the Yucatan that boiled the ocean, and rained down molten pellets called tektites thousands of miles away in the Dakotas and beyond that killed creatures caught in the open instantly, and clogged the streams and the gills of the fish, and choked life to the brink worldwide.

Other big creatures went before the asteroid in other extinction events, some lived after, like the megalodon giant shark creature featured in CARTHAGO, by French writer Christophe Bec, declared actually extinct sometime within the memory of primates in the last few million years, but now behold living presently in the mysterious deep. Such monsters once scared everyone away, yet over time the huge ones, the really scary ones, lost again and again to smaller, vicious neighbors, like sharks or humans.

The story of discovering a host of ancient creatures surviving somewhere near Australia made me think of an account by Arab ambassador Ibn Fadlan from Baghdad in the tenth century, telling a story of Viking lands far north where they came to a place embattled by inhuman creatures who plundered on horseback. The tale only came into English in the last century, popularized by Michael Crichton in a novel (1976) and a film (1999). The Eaters of the Dead story made me believe it was possible a pocket of Neanderthals survived within reach of the present era. Fictions fuse with actual history to make fantasies where we live today as well as ever yesterday it seems.

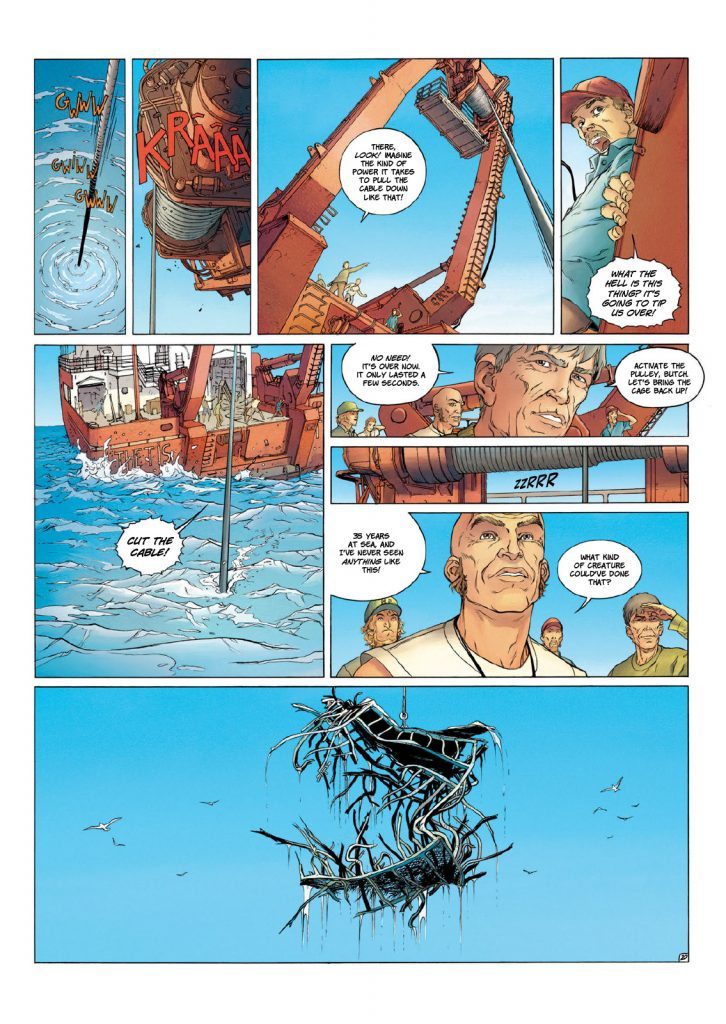

The pace of the Carthago story moves in a familiar European style, without splash, except in the fine art shared seamlessly by Eric Henninot and Milan Jovanovic through the course of five issues collected in a first hardbound volume, where excellent splashy water scenes above and below the surface predominate, along with sidelines into the Australian desert, on boats, a castle, and many other diverse places always filled with active people and events, sometimes deep in the past, shaping vignettes all bearing on the huge monster shark. Or do they converge there?

The name of the book refers instead to the giant oil corporation Carthago as the main actor here on the global stage even as boardroom members change. This is the huge monster firm so comfortably known today it takes a selfie with a fabulous monster to get the picture. Ordering an activist group killed establishes the firm’s criminal credentials, yet no accusations appear for anything, only small episodes that reverberate at the right moments, like a professor talking about large ocean creatures beaching themselves due to the massive disturbance of sea shipping lanes, those freeways of commerce out beyond the civilized world fencing nature underseas between overpasses clogged by thundering machines and garbage, emanating increasingly, like this book, from presses in China. Naw, it was just the big monster shark scaring them.

Another picture mentions the disturbance of drilling for oil deep in the plates around Malaysia, and eventually takes us to the coolest scene when the tsunami we know actually hit the beaches, submerges a whole city, and the monster shark whips down the avenues scouring for food. On cue, right when it appears appropriate, there comes a scene of the tyrannical passion of Captain Ahab from Moby Dick, pointing not to the whale, but to Ahab, like a neon arrow directing us back to Carthago.

The earliest humans loved the seaside. The remotest Phoenician sailors founded Carthage and other places along many coastlines, and planted monoliths like Stonehenge through North Africa, Britain, and the Baltic, and arrived even as far as Cuba, as indicated by Sicilian historian Diodorus Siculus from the time of Julius Caesar, writing “the Phoenicians were at a very early period driven by the violence of the wind far beyond the Pillars of Hercules, out into the Atlantic Ocean,” and after many days “discovered an enormous island that was fertile and finely watered with navigable rivers” soon known to the Carthaginians at home, but left undeveloped as wars with Rome escalated. Early commerce fertilized us all, civilized us all, yet finally Carthago coinage in its huge efflorescence suffocates. So we ask calmly in French where all beauty begins: Who among you will manage this beast?

*

NB. Acknowledgements to grad student Robert DePalma at University of Kansas for recent details on the Yucatan asteroid story in a May article in the New Yorker, as reported in the New York Times; and to Richard Turco and Carl Sagan for global modeling and explaining nuclear winter in the 1980s; and to Barry Fell, who wrote on the Carthaginians in America in 1980.