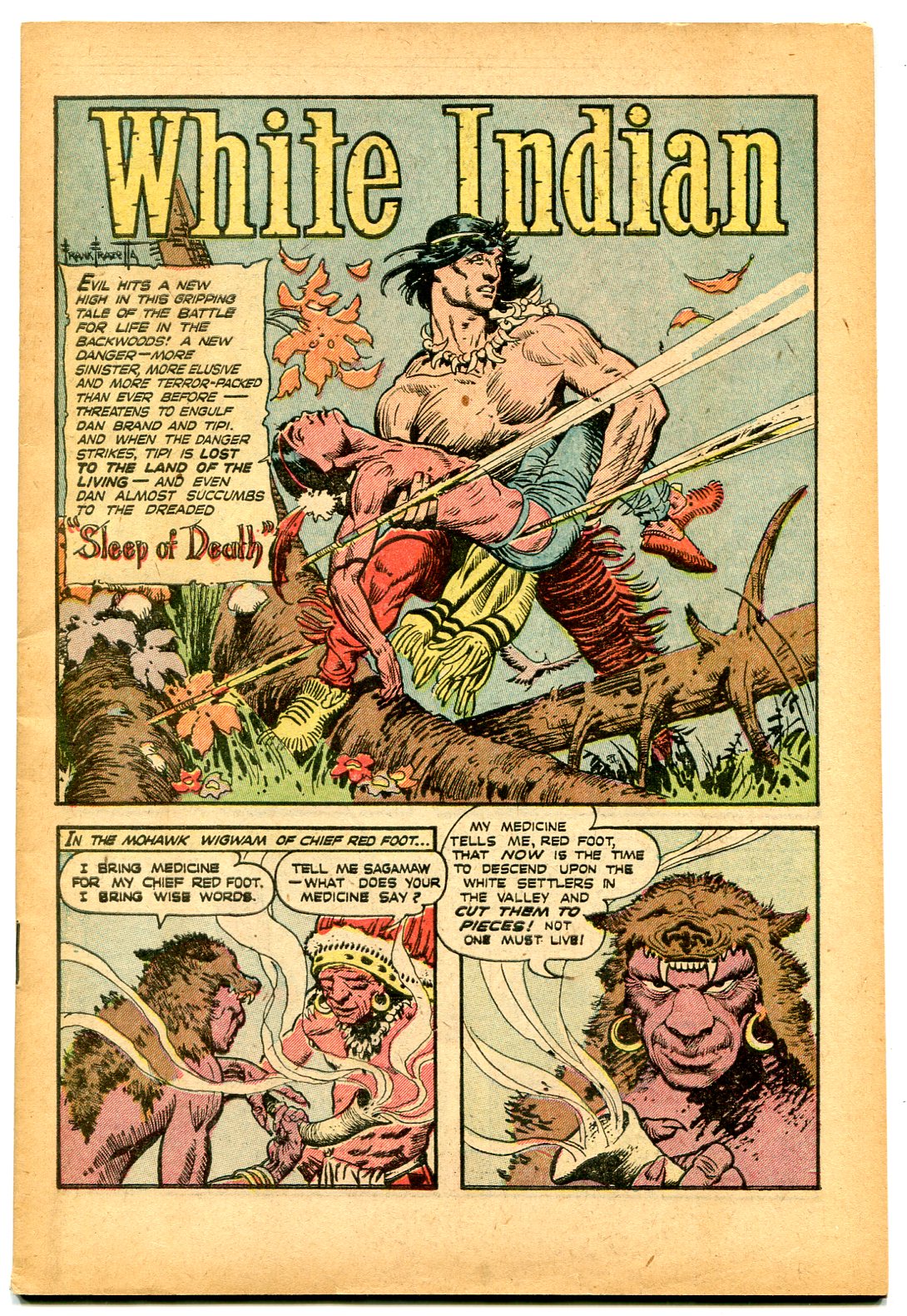

Writers: Anonymous editors

Artist: Frank Frazetta

Vanguard Press, 1981

MANY SHED TEARS for graves left behind, and search the detritus of past lives while names and episodes blow away, leaving only occasional sparkles of horror or heroes to supply a face in the era of our lost loved ones and the loved ones of others. Hauntings like this from real life rode over my first readings in White Indian, where I followed artist Frank Frazetta to a collection of his earliest works in second features from the 1950s, with added newsreel pages from other comics interspersed showing snapshots from the war in Korea, which had just begun, featuring real-action heroes in battle scenes happening right then with dads of friends of mine growing up, among others who never came home to become dads. Facing off with ghosts hovering around the Ohio River in 1770, spanning conflicts with gun and whisky runners, pirates, thugs, raging Indians, French renegades, Redcoats, and bears, and then Korea in 1950 all at once, gave me long pause in between stories. It makes sense to administer this series in monthly doses at the drug store as originally intended.

The first white Indian I ever saw was dancing naked outside an early French fort along the St. Lawrence River, according to historian Francis Parkman, deliberately mooning the inhabitants who watched on the ramparts, before he cavorted off into the ancient woods presumably to rendezvous with his newly acquainted ancient fellows. Christian pride in the ensuing centuries required attempts to repatronize such prodigal souls, both male and female, to prove civilization bests the ways of even the noblest savage. Personally, I was always unconvinced.

The opening origin story looks like an actual event, when a rival takes away one’s true love on the steps of the altar, and ensuing crimes lead to life as an outcast beyond the frontier, ending up with an Indian teen companion, mixing one’s loyalties between settler and native peoples. The pair fight for a host of fine phrases: civilization and justice, country and freedom, and not least, the right to control places to build great cities. It looks like a civilized country means scraping the land bare to redirect resources for maximum profit, exploiting speculative values per trip, per acre, per square foot as individual owners freely choose. You want to settle on those lands? “Then settle on those lands you shall!” exclaims Dan Brand the white Indian to a hearty band of settlers, ready to fight first to get their way.

Many of these combats in the woods look unlike the way Indians typically fought, more like the assaults familiar to a generation that just lived through a desperate world war, clashing and clawing through each other in wholesale slaughter. The anonymous editors who wrote these stories share in such anachronisms, though some silliness is due to the young artist, like showing two bulky guys carrying a log for a new fort, clearly unaware of the killing weight of a tree.

Such a moment shows the point of the story, though, exhibiting strength and fortitude in the wilderness to launch an iconic hero that could potentially leap into mass-marketing celebrity. Frazetta pays off, illustrating men in dynamic poses with enviable physiques. The figures are never wooden, the poses and action are magnetic. Only the bad guys look out of shape. Versions of ugliness scale from handsome virtue on one side to indifferent innocence to sloppy scoundrels. In all, the faces and hands could use less fiddling.

Superfluous errors startled me less than the mass of truths piled in so many of these now hackneyed scenarios and sentiments as when the rawhide dad of a beautiful daughter tells Dan, “You ought to settle down on the soil with us—raise a family—help start a city.” Elements of ideology sprout from this single sentence like a dandelion bouquet, alerting me most, because I was just reading how the ruling class in Europe formulated these ideas and sent out brochures to advertise exactly this opportunity, because they knew only with workers and residences and rising rents could they become rich forever; and it worked, capsulated in an idea communicated in a bullet point, repeated in 1950 here mouthing what a rawhide dad surely spoke in 1770, and another dad a century before that when the white Indian first appeared in French Canada. This is not a vague attitude coalesced in the spirit of the times; it was a deliberate policy planted and sowed to fruition in the lives of everyone, as we see.

Seeing this collection from the 1950s helps make sense why fascination in this era grew to favor science fiction and super heroes, recoiling from the facts of history that made us. It reminds me how I pause before picking up anything again from the 1950s, sensing distaste physically on the back of my tongue as the worst of decades for humanity in the coils of the new American empire, true enough, until I rightly recall all the other decades in America since that first white Indian.