Creator: Tadao Tsuke

Drawn & Quarterly (2015)

A market is a place where you can sell your goods. A market is also a place where you can buy stuff. This duality underlies a difference between passive and active roles, a duality which is never crystal clear: those who sell both offer and receive (money, usually), just as those who buy both look at and are drawn to what they think they need. The same can be said about the act of reading: when you open a book, be it one with words only or one with pictures (for adults, for youngsters, for children), the end result is you being led throughout a story someone else has been writing for you, just as much as it is you who decide that that book should be read (the hand that turns the page can be stopped, putting an end to what some might see as a pointless action). It is therefore to ask what kind of goods mangaka Tadao Tsuke is asking us to buy from him.

The idea of reading to escape reality and its horrors is to be discarded from the start. This collection of short stories are not to be taken as a way to find a world where adventures await us (and the characters in it), at the end of which all is fine and dandy. All is lost in Trash Market, and there seems to be no way to restore a theoretical past greatness, as the world goes on, moving elliptically around the sun, while the men living on our planet try to make ends meet in what is the outcome of a catastrophe. The Japanese post-war setting of Tadao’s short stories is indeed a place where no man would like to live in, and the economic and societal structure is such that no escape seems to be attainable. Awful as things are, you either learn to live with them or you disappear: the “eat or be eaten” diktat we are faced with cannot but make us feel sick in the stomach.

The fact that there is no possible – or plausible – salvation does not mean that things cannot get better. Such a statement, an overbearing nihilism, is not what Tadao is trying to convey; if he were to do so, the end result would be less powerful than it actually is. It is indeed to be noted that there is no general transcendental entity of evil at work, rather a simple matter-of-fact reality that shows what kind of persons peopled post-war Japan. If the context the six stories goes against any kind of rosy vision we might long for concerning reality, this is the normal outcome of facing the state of affairs exactly as it appears: the world is ugly because the world is ugly, a tautology that simply highlights the fact that sometimes bad things happen and that certain situations may exacerbate a tendency towards bad behaviour. It is not that we are evil, it’s just that in this particular moment we are led to be – and act – so.

The structure of the stories is such that they flow apparently without any particular aim. The meaninglessness of the outer world is therefore mirrored in and by the loss of any kind of sense the stories should possess, just as we have been taught to expect: a beginning, a middle, and an end. Yet, this is exactly what makes Tadao’s work so enthralling, as if we could not shake them off our memories, as they keep lingering on. The stories here are not supposed to be taken as complete in themselves (it seems that Tadao himself never wrote them knowing already how they should end), rather as the act of capturing parts of something bigger, that is, the lives of their characters. We are being made privy to something that would usually go unnoticed, an aspect of man’s life that does not seem to deserve to be made the centre of our curiosity: the characters we are being presented do not, in fact, seem to be vested in that kind of divine aura that makes them stand out. And this is what makes Trash Market a joy to read, at least for those who can stomach it.

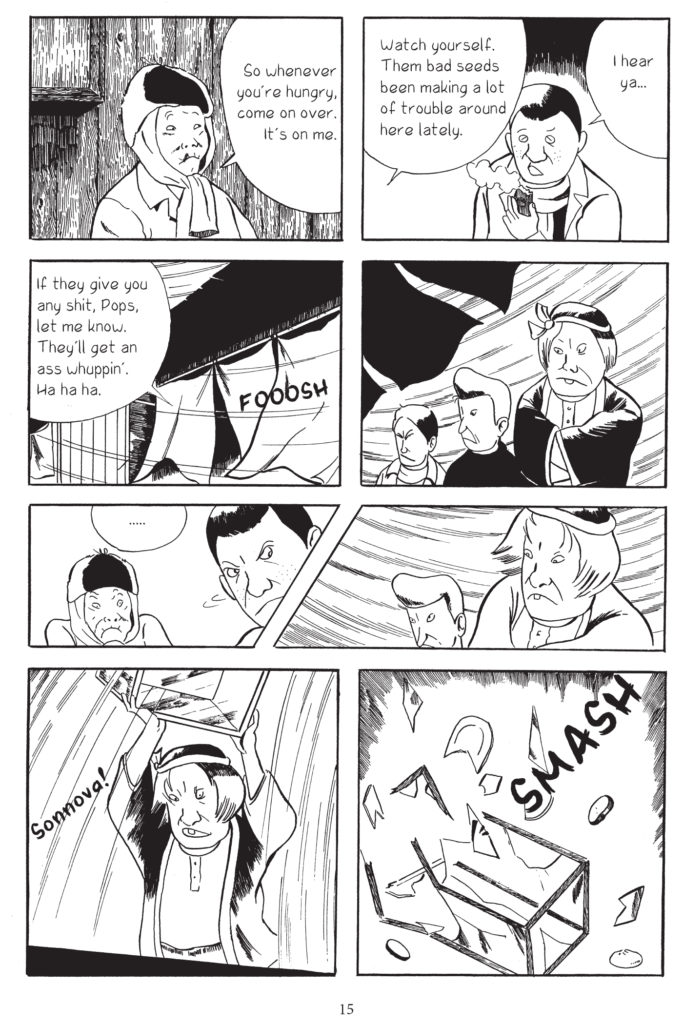

There is nothing sickening about the art, crude (yet powerfully evocative) as it may be, but the overall feeling that comes out of the mangaka’s stories is such that there seems to be no way of not letting ourselves turn the page to breathe in the world that is being described. A word not casually chosen, “description” is therefore what best gives us a general idea of what Trash Market is: Tadao is not imagining, rather re-imagining, taking those very situations and characters he knows so well (the second story, for instance, is mostly autobiographical, while the last is set at a blood bank, the same place where the mangaka used to work) and remodeling them so to serve a new purpose. The world we look at, in other words, is as real as it gets (or was, at least, being that we are taking about last century’s fifties).

Violence, in all its forms, takes centre stage, a violence that can be either physical or psychological. But such violence permeates the world the characters live in, both as an outcome of who they are and as the cause of their acting that way, therefore creating a vicious cycle which it seems hopeless to take distance from. It is for this reason that once again it is impossible to talk about an ontological dimension of evil, as something that fights against humanity; it’s humanity itself that breeds such evil, just as this evil is caused by society, an entity, this latter, that is made of – and by – individuals and yet does not need every individual to exist. The above mentioned nihilism is therefore not a philosophical stance, a sought-after way of living that stems from long pondering; it is the natural outcome of a dire situation where man is reduced to trying to survive, coping with a present that prevents us from thinking about the future, enslaved by a past that in its bountifulness (a Japanese empire) was doomed to perish.

There should be light at the end of the tunnel. The last story, after all, ends with rain following the long days of a scorching sun and its unbearable heat. Yet, it is difficult to find catharsis in the stories contained in Trash Market. What seems to be the end of a tale is in fact just a moment that has been encapsulated, the description of a moment (or moments) that is (are) part of something bigger. We have no idea in regard to what is going to happen, whether the characters will all be saved or whether they are going to fail. The characters are not heroes, and they show no sign of being such creatures. If there’s a lesson to be learned, this might be the one: we are not princes and princesses, rather the bricks that make up the wall we call humanity. It would be obscene to think otherwise, an injustice to our intelligence. Nihilism, then, be gone, but let not false hope take your place, lest we forget that we’re all part of a market where we sell ourselves to each other so that we might live to see another day.