Creator: Emma Evans

2020

This is a non-fiction diary of the beginnings of the Covid-19 pandemic as experienced by an artist in London. Emma Evans turns 30 during the course of the pandemic. Without any intention of being patronising in any way, she is a young person, in an industry which is fickle at the best of times, trying to cope with isolation, uncertainty, and not a little despair. She succeeds, admirably.

Anyone who watches news out of the United Kingdom is aware that the Johnson Government’s handling of the crisis has suffered the distraction of a calamitous Brexit. Even after Prime Minister Boris Johnson contracted the coronavirus himself and was for a time on death’s door, the British health strategy seemed disorientated, torn between saving livings on the one hand, and a desire not to infringe on people’s liberties and the preservation of the economy on the other.

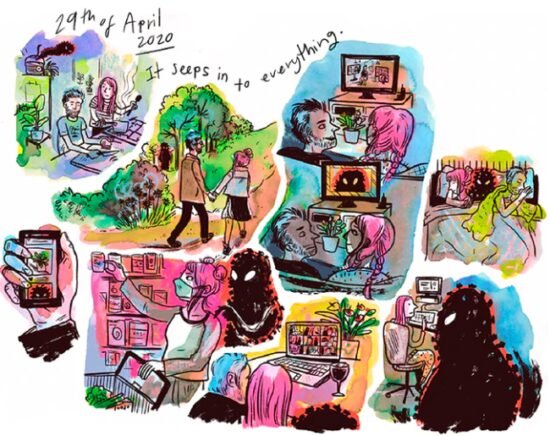

The day-to-day consequences of this meandering policy are captured well in this comic. Things are strange. Ms Evans notes that activities like going to the supermarket are now unpleasant and alien, rendered in bright post-modernist Orwellian plastic, signs pointing the way to go and warning about physical proximity with other shoppers. Ms Evans’ boyfriend dyes his hair purple in a fit of ennui.

There is too much time, and that time comes with an adrenalin-trickle of apprehension. Part of the experience recorded in the diary is, with respect, is a generational issue: the interconnectivity of technology, something those of us who were in the IT industry in the 1990s called convergence (an archaic word, now, in the context of internet devices), means that people who grew up in the 2000s have been nurtured by velocity. There is a constant delivery for news and information, from friends or news outlets, updated by the second.

Then, pandemic, a high speed handbrake and flip of the car on the highway, where the news is uncertain, and information is measured in ever increasing increments of infection and mortality. Words like “co-morbidity”, “mutated strain”, and the genericised brand “Zoom” have entered common vocabulary. For a generation bred on “next”, the medieval fact that the next “next” could be death is a jarring turn.

Old-timers like your reviewer grew up with the spectre of nuclear war and the mournful dirge of Sting’s 1985 song “Russians”. Ms Evans as a young adult faces the spectre of an invisible pathogen. This diary is her song to her epoch.

And Ms Evans, a person with an innate autobiographer’s skill of standing back from herself and documenting her vibrant emotional spectrum, feels it as hard as anyone. The text is colloquial, and as it is recorded periodically as the pandemic accelerates in severity, and it is stripped of any sort of revisionist gloss. Ms Evans is worried, and that worry sometimes is subdued, and sometimes borders on despair. But it is always there.

Overlaying this dire experience are Ms Evans’ wonderful watercolours. The sketched art is enlivened by pastel shades, so that despite the sometimes depressed and frustrated language, there is always the sweeping palate of colours rendering each page a beautiful piece of art of itself. Intentional or not, this suggests to the reader to whom Ms Evans is otherwise a stranger that there is something fundamentally positive about her character, expressed not in her pens but in her brush and palette.

Even the front cover, featuring Ms Evans staring pensively out the front window of her house, is emblazoned with a rainbow of muted watercolours, green and yellow and blue entirely reminiscent of Chagall’s early Paris body of work. It is both thrilling and lovely.

And the colours seem to presage other ways of life, adapted to conditions, but fun and community-orientated. Ms Evans and her boyfriend cycle through the verdant English countryside, enjoying vistas glimpsed prior to the pandemic through the blurring windows of a car. Mr Evans plants vegetables. People in her neighbourhood anonymously trade plants. There are poignant moments of distance – picnics without hugs of greeting, birthday parties with vulnerable aging relatives via teleconference – but, over all, Ms Evans paints her experience with the sort of enduring hope that is best fuelled by, and expressed as, art.

This diary is a very personal thing, and we are very fortunate that she has shared it.

Virtually The Same was the subject of a Kickstarter campaign and was 371% subscribed. It is available for sale here: https://www.etsy.com/uk/shop/TEEhasashop