Writer/Artist : Naoki Urasawa

Publisher (for the English market) : Viz Media LLC

Year : 2018 (Japan/France) – 2020 (English market)

The review is based on the Italian edition of 2021, published by Panini Comics – Planet Manga, translated by Mayumi Kobayashi

It goes without saying that when asked to name a list of museums, it might be difficult for the interviewee not to say “the Louvre” – or, as the French say, le Louvre, with that kind of “r” that few can pronounce, especially in the English-speaking world. A place like this, which tourists are drawn to, represents an imaginarium that art-lovers – be they pros or amateurs – cannot but appreciate as the epitome of what a museum should be: rich in diversity, both geographical and historical, it lets people immerse themselves into its many paintings (and sculptures). That allows for a proficuous act of spending our precious time both educating ourselves artistically and enriching our minds aesthetically. A necessary step into becoming a citizen of the world, the Louvre may have become part of a modern grand tour whereby we can state that, yes, we have seen La gioconda (even though, truth be said, the Last Supper in Milan is a lot better, or so I’ve been told).

Back in the years before the pandemic, in 2014, Urasawa Naoki, the author of such masterpieces as 20th Century Boys, its continuation 21st Century Boys, and Monster, was asked by Fabrice Douar to produce a story that had the Louvre at its core. The idea sprang from the fact that, finally, comic books were being given the label “artistic production/expression” by the French museum, thus ending the everlasting diatribe over whether comic book readers were wasting their time or not (the diatribe is nonetheless absurd, as readers are actually wasting their time or experiencing art depending not on the medium but on the content).

Mr Urasawa accepted the invitation, but had to postpone working on the project as he already had a full plate. Time went on, then, and other creators published their very own homages; when Mr Urusawa found himself free he thought too many years had passed, yet Mr Douar had been patiently waiting and found no reason not to give the green light to whatever the mangaka wanted to write and draw. So, this is how Mujirushi came to be.

The structure of the short novel is such that it plays on the idea of occurrences, that is, things that happen because they have to, where an apparent chaos is supported by an inner mathematical architecture. Whatever happens, in other words, leads to an unknown consequence which, by its very nature, manages to put things in order, keeping a balance between the expected and the unexpected.

What we take from the story, then, as is usual in Mr Urusawa’s works, is the kind of serendipitous events that would actually make no sense in the real world (unless we stand by Jung’s synchronicity, this idea being something known as pseudo-science). But the overall idea that all is well that ends well is not such that the final outcome is either expected or obvious (the two may be seen as synonyms), which means that we, the readers, are not going to be robbed of our time; the story, if other words are needed, is not so banal, and the structure, in what might be called its average complexity, never stops making us wonder what is going to happen next.

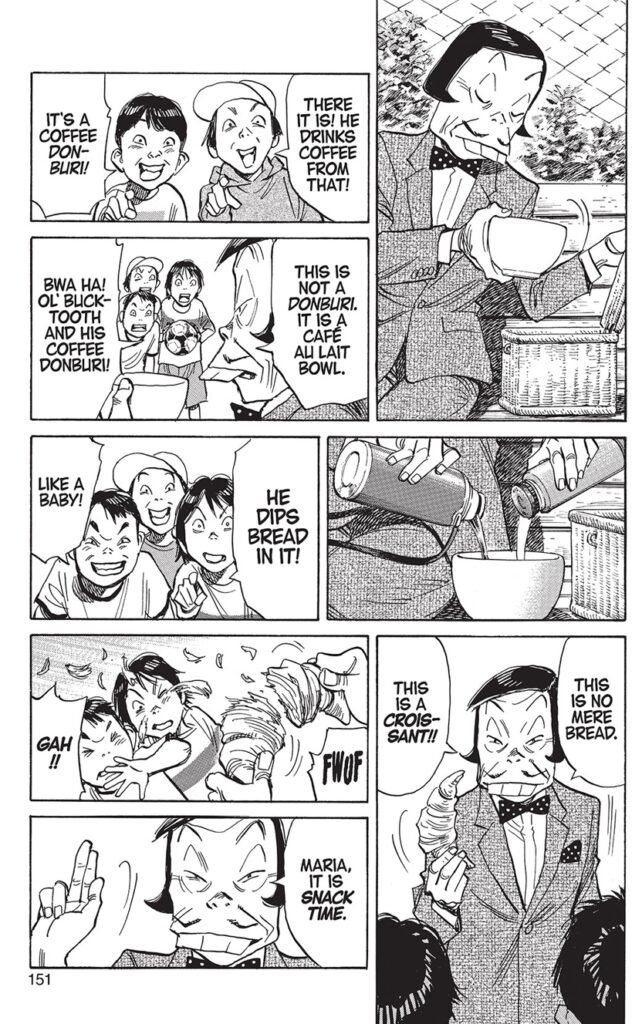

Such complexity is mirrored not just by what goes on, but also by who is there to lead us through the story. A mosaic of characters, it is quite difficult, in the end, to state who the protagonist is, even though the kid, Kasumi, would be an ideal candidate (but, how could we forget Michel or the mysterious man who knows so much about France, France being a place he has never visited – at least, this is the conclusion all the clues seem to lead us to).

There is, then, a feeling of interconnectedness, a game between casuality and causality where both are part and parcel of a structure that hides itself under the dexterity of the dialogues and the beauty of the panels. A short novel that can be experienced in a silent afternoon, what we are left with at the end of the story is a feeling of elation, of “things-going-the-way-they-have-to”, even though we know that this is so because there is someone guiding the pieces on the board, a writer whose cleverness and virtuosity lie in the ability to hide his hand behind the panels.

There remains for us to ask ourselves if, after all, this is actually a short novel about the Louvre. While there’s little denying that the museum is part of the story, we might also be left wondering if the Louvre plays an important role because of its ontological status in the comic (the Louvre, only the Louvre, could have given birth to this), or whether any other museum would have sufficed.

It is also true that, perhaps, the isn’t much you can do with a building which, in its essence, is just a blueprint that can be reproduced anywhere in the world, that is, unless we take its history and its idiosyncrasies into consideration. Mujirushi should then be seen, at least from this point of view, as a tale that uses that French symbol as a canvas over which a story can be painted; those interested in everything that has to do with the Louvre will surely find it to be a decent addition to their collection, yet those who would like to analyse the work in more depth in regard to the links between the museum and the comic book might end up reckoning the file rouge to be a bit too flimsy.

Not that it detracts from our overall feeling of being in front of a little, if not minor concerning the artist’ production, piece of art; a nice read to make us wonder at Mr Urasawa’s deftness in building a structure that balances itself between gravity and joyfulness.