Writer/Artist : Gustavo Roldán

Publisher : Malpaso Editorial

Year : 2018

Language : Spanish

Hats, so we are told, are objects we put on our head. Hats, if we are not mistaken, can protect us from the direct action of the sun (warming up our brains to not too delicate temperatures) or the fangs of snowstorms and freezing winds. They do serve a purpose, but it would only be half of the deal, the other being the fact that hats can also be used as a way to create a persona that we wear daily when having a conversation with other fellow humans. Hats can become part and parcel of who we are. Donald Duck has a hat (from time to time), Popeye has a hat, Dick Tracy has a hat, Corto Maltese has a hat, so why couldn’t a circle with a very minimalist body have a hat too?

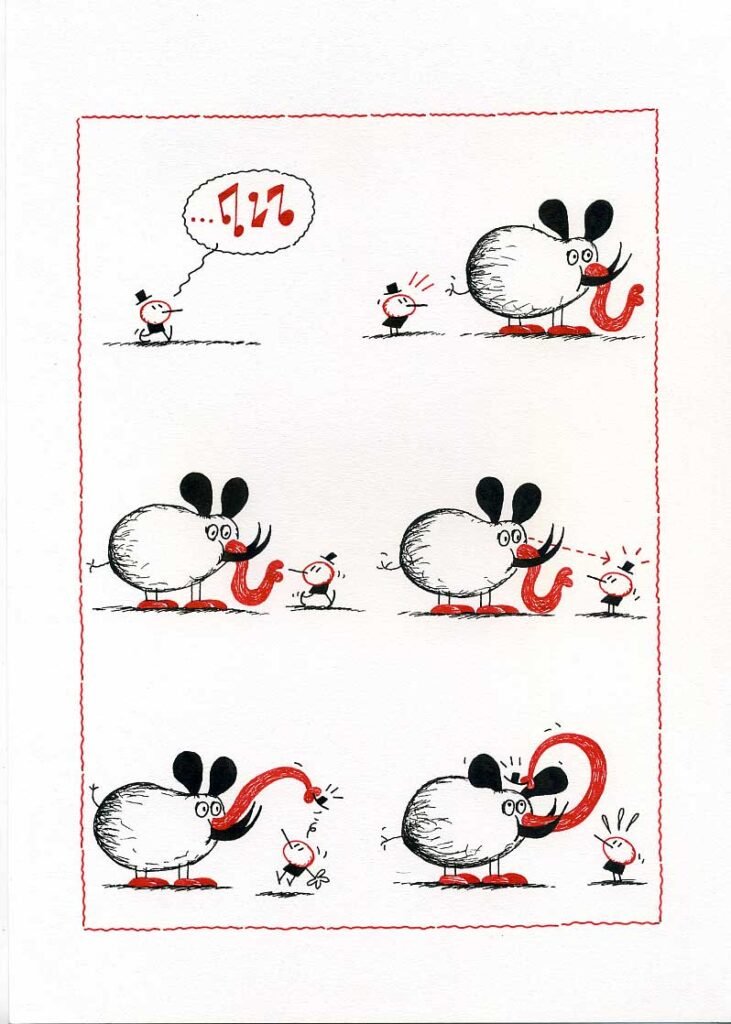

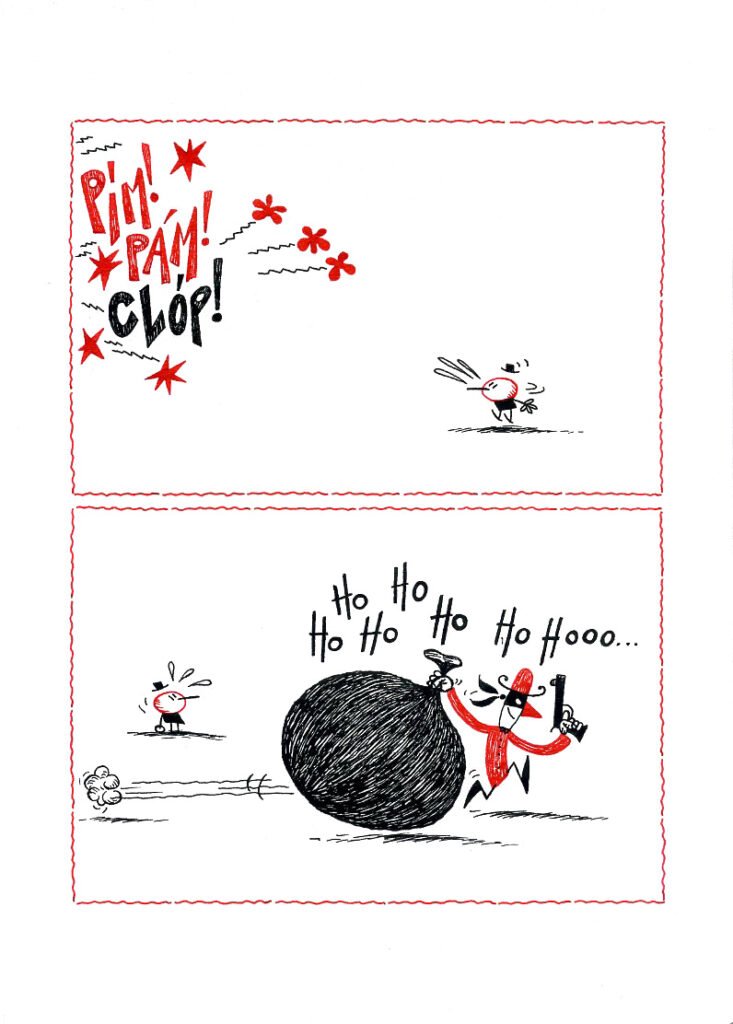

Gustavo Roldán’s Un hombre con sombrero is a book that contains less of a story and more of a series of vignettes that revolve around a main character whose name is never uttered (not even hinted at). We are presented monsters, birds and a few human beings, not even one of them possessing the duality of name and surname. Not knowing who they are, they cannot but be reduced to a series of words (nouns and adjectives, or the like) that make us feel less assured of what we are seeing. An elephant, for instance, is hidden on a tree and needs our hero’s help to come down (it is not known that the animal is hiding there, between leaves and branches). What do they represent, then?

Freed from the shackles of names (Wittgenstein might have been amused by this), the characters in the panels are given the chance of being who they want to be without having to raise their hand when they hear someone say the words that locate them both physically (Where is Gustavo? There!) and abstractly (Who is Gustavo? An artist).

Such freedom is not wasted, and imagination is given the front seat, although not the one that looks at the screen (or the stage), rather the one that looks at the audience (from the screen, from the stage).

We have to accept, then, that we have left the world we inhabit and that we are roaming through uncharted territories, not because what they do theoretically has never been done before, rather because we cannot know what to expect (unless we expect the unexpected, which is a philosophical problem, first and foremost).

There is therefore beauty in the panels, as page after page we are treated with a long, unconnected chain of events that revolve around the loss of the objective grip reality has on us. There is no reason to read the book if our goal is that of being told a story that we can relate to, set in a world which is more or less similar to ours. There is no lesson to be learned, nor is there an overall sense of morality, of an ethical tour de force where good must prevail over evil. There is not even evil per se, nor good.

As space is given to the practical cleverness of nonsense, we find ourselves immersing our heads into a place that is, by its own tacit definition, a non-place. As odd as it may sound, and as absurd as it may appear to be, it is this very absurdity that makes it possible for the book to be more logical in its intent: Roldán is here to amuse us, and to amuse us he knows we need both to forget the rules that act as pillars for our daily lives and to accept that nonsense can be such only if there is a sound mind behind it.

There’s common sense in madness, after all.

A thunderstorm of perfect logic, then, this madhouse is such only to the untrained eye, the one that tries to look at the world by donning the bespectacled visage of the logician who finds himself too linked to the world of (in)sanity we live in. There is much to gain from letting the man with a hat take our hand and lead us into his reality. We feel we are being made privy to a series of events that never would have occurred to us, unable to say what is coming next, nor to deny them their reason to exist.

There is logic, once again, in flying and then falling once we are told that feathers are to be moved quickly up and down, feathers that we, like the man with the hat, don’t have.