Creator: Howard Chaykin

Image Comics, 2019

WHAT WE FOUGHT FOR in World War Two against fascism is supposed to be abundantly clear. Freedom. From an American viewpoint, the placard found at a German concentration camp, “Work makes you free,” seemed like obviously evil logic. Beginning the story here in the aftermath, in 1945, we see what freedom looked like in America where a newly-won command of the world was about to unfold. This is where author and comic artist prince, as he dubs himself, Howard Chaykin brings us to look behind the comic book page into the lives of those who made them at a quoted rate of six pages a day, hired drudgery and glad to get it in the land of free enterprise; not quite freedom.

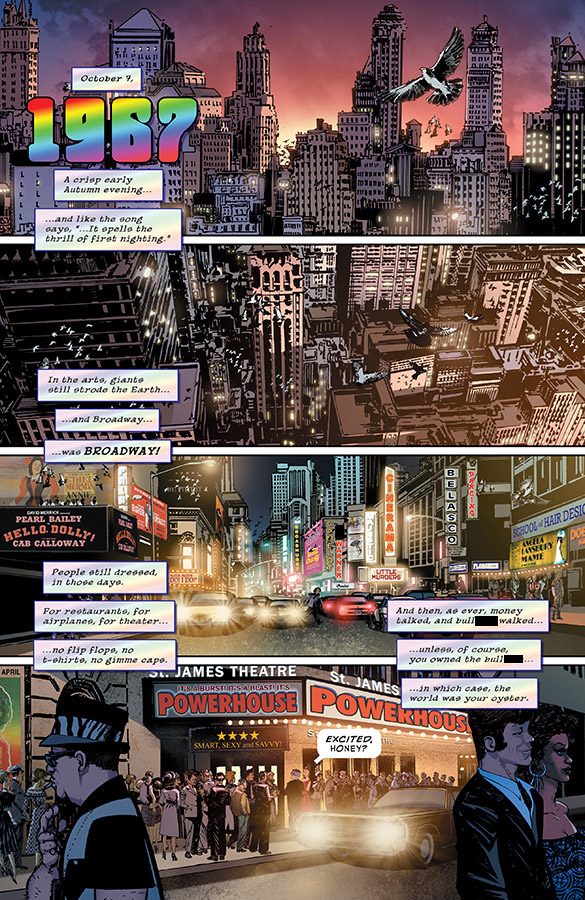

The five-issue story collected in a graphic novel runs in decades, giving snapshots from 1945, 1955, 1965, and 2001, running in a series over and over again with additional details, intending to tell real history with the names changed. In the final issue a glimpse moves to 2015, and back to 1937, to finish a main theme related to trademark issues between business owners and artists: a familiar story of exploiting talent as recording studios did in the same period for musicians, and publishers for writers, purchasing all rights for a fee upfront, gratefully accepted by artists who could hardly comprehend the potential of mass markets, and the vast wealth in store for the one percent of the one percent at the top of the food chain.

In an afterword, Mr Chaykin explains exposure was not his intent. The record is all he wanted, and the record he knows is the comics industry. In many respects, the characters could be anyone in any number of other industries. Real people become caricatures, who then become types, giving faces to abstract concepts, and history comes alive. Featured this way, the most common concept is “asshole,” which gets attached to a lot of faces.

But why? I found myself asking. Why did it have to be a job was so hard to find that people fought for recognition to become one of the chosen, and demonized those who did not deserve to be there, or exploited others? Full-time employment was hard to achieve anywhere. This is one thread in the weave.

Hostility was also directed toward those who were paid enormously and unfairly beyond their actual contributions to the enterprise, merely because of position or ownership rights. Under liberal capitalism, any way you can make money is allowed. The story sometimes mentions that criminals have at least been cleared out of the business, but this is a mistaken perception. Crime simply changes its colors, as Lincoln Steffens showed at the turn of the previous century. Once a scheme is exposed, others are developed that do not arouse public censure. Corporate crime is ever called yesterday’s problem, like we solved that.

A pervasive feeling of being treated like a second-class citizen oozed from the Jew, the black man, the woman, the homosexual, the talented, and the untalented, reminding me of Thomas Carlyle writing in 1850, in The Present Time, when the Irish were starving and landlords thriving, that none are “so authentically slave as you are” who have been emancipated, relived in our time. Scenes giving a say to any one personal category, like hey, I am a minority, seemed absurd when everyone is there elbowing sideways, knee-deep in assholes.

Slavery by lack of direction eventually turns into slavery by direction; anarchy breeds authoritarianism, where might makes right. Panels from 1955, in the era of the Great Fear, showed demagogues spouting moral values as conventions for everyone and burning what was deemed unfit. The loudest voices swerved public attention. Mr Chaykin memorializes the moral panic that brought Americans to gather around bonfires burning comic books collected from neighborhood kids, starting in 1948 and running through the next decade.

This is the only time the title is used in the story dialogue, when a character says, “Hey kids … comics,” walking by a bonfire with her own work on the pile. Rethinking what freedom looks like needs to include the themes in Hey Kids!: how we work together and encourage enterprise to draw work from our best talents in the first place. They don’t just gush like a hose on their own.

And make positions from which it is not fatal to fall, and profits that match value and demean no one.

And finally, work on courtesy and common values, even conventional standards, so censorship discussions are standardized as they are already in local school libraries and their communities where it remains unacceptable to simply rely on free speech to approve indecent exposure.

On this last point of defining values, Mr Chaykin portrays the demagoguery of moral outrage as fanatical and dangerous, and this attitude needs attention all on its own, as relevant today as ever. Taking a graphic view of the past seventy years as Hey Kids! does may help us focus on such perils in our time, the time we won, and imagine who we want to be instead.