Writer and Artist: Carlos Giménez

The review is based on the Spanish “Todo Paracuellos – Edición conmemorativa 40 aniversario”, published by Debolsillo in 2016. A shortened English version was published in 2016 by IDW, with a preface by Will Eisner.

When Civil War broke out in France, the idea was that two different, opposite points of view were clashing: on the one hand, we had the Republic and the sanctity of democracy, on the other, the trinity of Dios, patria y familia, three words that ultimately acted as the pillars of the fascist state. The republicans lost: they had started an internal fight for power (the Communists didn’t want to work with the Anarchists, for instance), and the Fascists were being helped by the Germans and the Italians (not officially, although it did not matter much). The aftermath was terrible: Spain closed its borders to the outer world, becoming a relic of a time never to be forgotten. Poverty abounded, and the Church found itself (once again) in a position of power.

This is the setting of Carlos Giménez’ masterful graphic novel. A country torn by the memories of a civil war which had just ended, where homo homini lupus was not a phrase that had nothing to do with the present. There is evil in the characters who people these pages, yet, such evil is not of the kind that lurks in the perennial fight with good. If bad characters are bad, they are so because the context does not allow for innocence to be praised, nor to be cherished. Children need to grow fast and, to do so, they have to get rid of the hope that one day things will get better. Out with abstract concepts, then, in with the concrete weight of reality: if you are hungry and if you think you are not being fed enough, this might not be your imagination, but the stark truth of the land you live in.

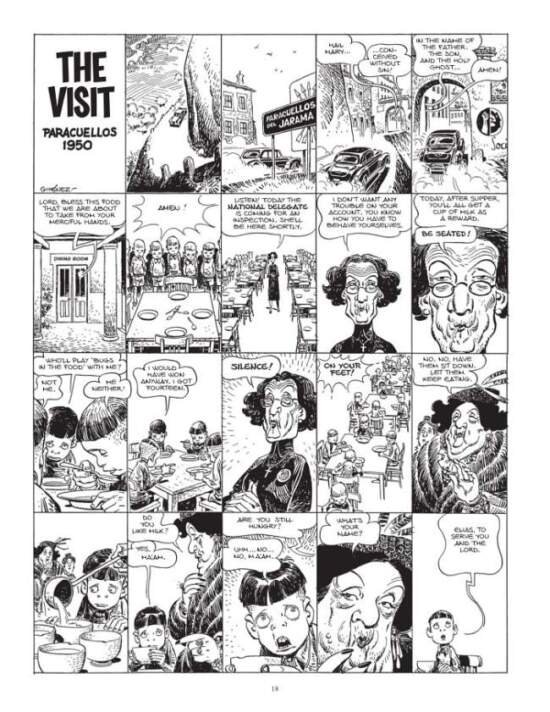

Paracuellos is the representation of many places a post Civil War Spain found itself full of. Places where children with or without their parents were sent to in order to (a) survive and (b) not be a burden to society (or the family). While the latter meant that their parents did not have the means to look after them and to feed them properly, the former should not be seen as simply the result of not there being enough food. More than just orphanages, these institutions exemplified how the familia had been lost to a post-war context where food was scarce, jobs were difficult to find and, perhaps more importantly, long work-hours and only a bunch of pesetas at the end of the month did not (nor could they) be enough to keep a child at home.

Yet, the disintegration of the traditional family did not stop from creating a new one based on the concept of fraternity. Nothing could be farther from reality, then, than thinking that victims are, by nature, ready to stand by each other and give one another a hand. The children in Paracuellos, indeed, are divided into perpetrators and victims, the latter being weak, the former being violent. There is a vicious cycle of frustration, of hostility and of sadism at work, here.

It is left to us to think what led to such a situation, where humanity seems lost, both as an abstract concept (being humane) and as a biological feature (being human).

There is no cynicism in the stories. There is not even a main character, but a storm of faces that come and go, and that highlight the anonymity and the universality of what is being told (and of the place it is set in). There is no sickness in the stomach, here, a sense of impotence; all the opposite, there is lucidity, a clear vision that does not try to sugar-coat a situation that possesses, in its simplicity, the unpleasant obviousness of a fact. What we are left with, in the end, is the experience of a world that can show its worst face without feeling guilty for it. Historicity apart, the necessity of bearing witness, the readers end up wondering what to make of the book, as if, by its intrusion into their lives, the result is more a feeling of uneasiness than nausea. The lesson to be learned opens up a series of sinister thoughts camoflaged by simplicity: man is in fact evil, and innocence is sometimes a matter of who we are than of the experiences that forge us. Men can be wolves barking at each other. But children, sometimes, can be even worse, too young to differentiate between good and evil, only the simple and stark nakedness of reality.