Uzumaki

Writer and Artist: Junji Ito

Publisher : Viz, 2013 (originally 1998-99)

Horror requires the creation of a structure putting into motion a feeling of uneasiness. We are supposed to find the fictive world in front of us so unsettling that, in the end, we start shivering. There is, in other words, the necessity of there being a response, biological and mental, from us as readers (or as spectators). It is not just the simple apparition of a monster, of a creature we recognize as not being part of the universe we inhabit. Rather it is the certainty that something is not working as it should, that the outer and inner worlds of humanity are not as they are supposed to be. It is the discovery of the fact that we always thought the world spun on its axis whereas the latter is tilted a little to the left (or to the right); the loss of this element of naturalness, of the world being as we have always pictured it to be, ends up in our losing our grip on reality.

Uneasiness, then, becomes the biological response of an abstract element, and the eyes that look away from the page (or the screen) are the exemplification of how fiction (that is, what is not real) can condition the concreteness of our existence.

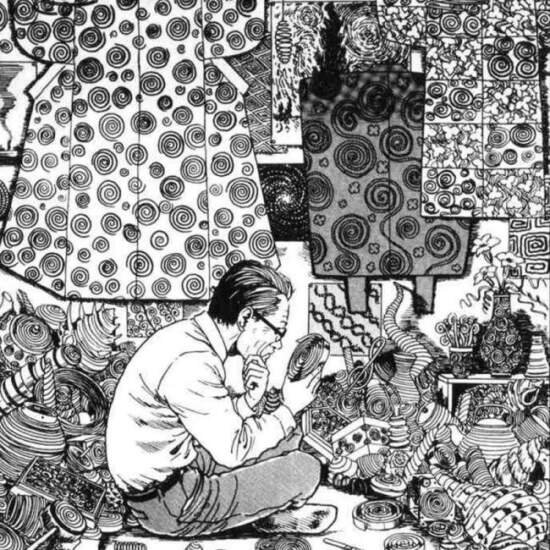

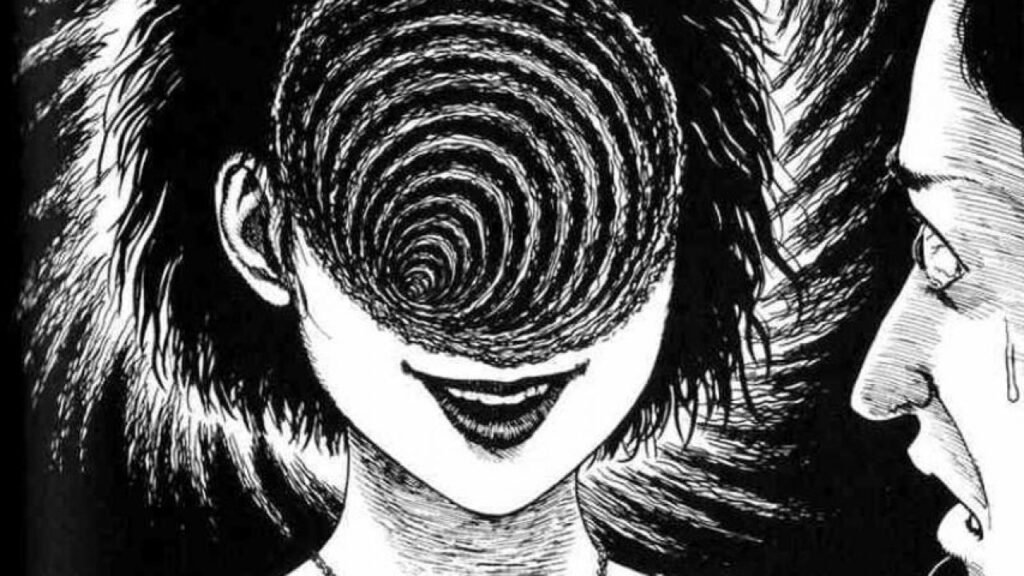

What we have in Uzumaki is a simple idea: spirals are unsettling. There is nothing more to be said, actually, as this is the basis of a long series of short stories presenting us two main characters (a girl and her boyfriend). The simplicity of the premise acts as a catalyst for Junji Ito’s dark imagination, presenting us a descent into madness which takes place over time, little by little, until all that is left is the indifference of natural elements. There is no evil per se, then, but what we (subjectively) call so, as the external world does not care for humans and their (our) preconceptions.

The destabilizing factor, if we follow this line of reasoning, is not spirals as such, rather how they seem to have a life of their own, detached from a universe which we thought had been made just for us, men and women: the realization that the external world is not ours cannot but lend credibility to the fact that we are not the centre of any given cosmos.

Yet, the beauty of the story does not simply lie in its simplicity, in the fact that spirals can be the means to highlight how unimportant we are in the grand scheme of the universe (but, at the same time, perhaps what the story tells us is that nothing has any kind of importance). There is a strong sense of claustrophobia, of that moment when our breath is cut short and there is no way of replenishing our lungs with oxygen. There is, in fact, the effort of the main protagonists to leave their town, a centrifugal force which is frustrated by a centripetal attraction that leaves no way of escaping. Here, then, is where another terrible idea opens up in front of us: the characters cannot escape the absurdity of their town because they, innocent victims, are bound to it by the simple fact that they live there.

There is no divine reason apart from the sheer bad luck of being the proprietor of a house.

The biological response we talked about at the beginning, our eyes looking away from the page, is a true fact, a normal natural response to the insanity of the pages, an insanity which is such if looked at from the point of view of us human beings. If Uzumaki unsettles us, it is also true that by so doing it manages not to escape from our memory: just as spirals become an obsession for the inhabitants of the cursed Japanese town, so does the book become a dark source of entertainment.

We want to know what comes next, what the following step into this madness is. It is quite telling of how we, as readers, function, taking pleasure from what is not, in itself, pleasant. Yet, obsessed as we may be by the book, there is an end to it all, and when the last step is taken in the long descent inside the belly of the town, the Lovecraftian element, reworked by the mangaka, is made apparent; we are nothing in the grand scheme of an illogical, yet well-ordered, universe.