Writer and artist: Takashi Fukutani,

Weekly Manga Times. 1979-1992

The review is based on the Italian edition, a “best of” containing a couple of chapters from the original manga. For the English market, please refer to Black Hook Press.

There’s something about life that sometimes does not work properly for us. We have dreams, we see ourselves become someone important, a name recognizable everywhere. It is not something too different than what our parents hope when they say we are going to become doctors (or whatever profession they might have chosen for us, driven by hopes for our futures).

The idea underlying this all, then, is that there is something special about us, something that makes us simply better than our peers, be it our intelligence, our willpower or even just our looks. We are, in other words, the epitome of human progress, a biological improvement compared to those who have given us life, a new kind of human being, even a new species that basks in the light of perfection.

Such hope, of course, is often crushed under the weight of reality, as we all, in the nullification of our importance, end up being more or less a mediocre product, going to school, to work and to the coffin in a matter of a few decades. There’s a little bit of irony in all this, perhaps.

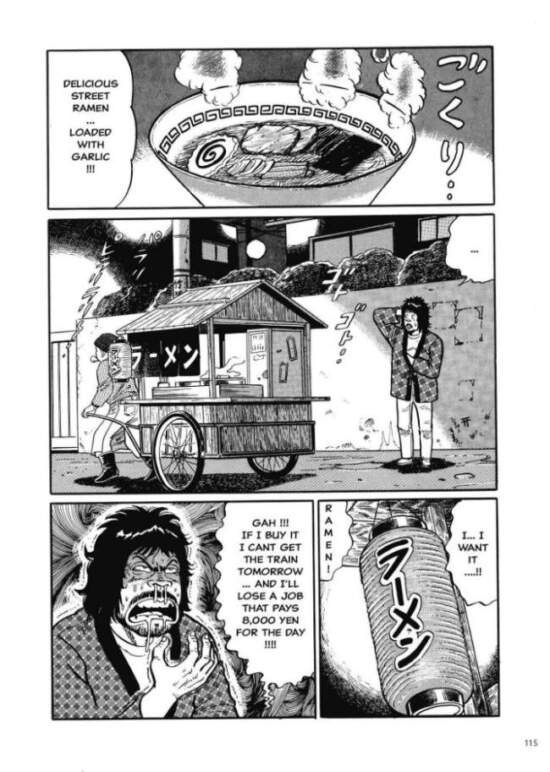

The heroes of the world of literature, then, tend to exemplify this need of progress, of fighting against an adverse fate and manage to win (to conquer) a better life. Yet, not all heroes are such, and the greatness of mankind can become, in the right hands, the subject of ridicule. For one person who manages to reach the top of the mountain, for instance, there are thousands who stop midway, just as many who can’t even start at the bottom. Yoshio, the main character of Takashi Fukutani’s manga Dokudami Tenement, is one of the latter. Penniless, always hungry, always trying to find a job to satisfy his needs, sometimes slaving off, sometimes slacking off, he is not, surely, a role model, that kind of shiny specimen we all would like to be like.

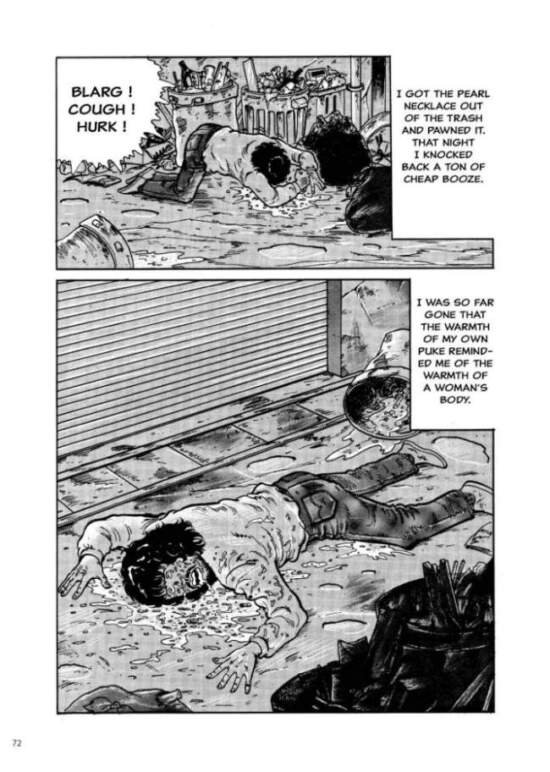

Yoshio lives in squalor, both physically and mentally. There is a grotesque feeling, then, acting as the pillar the stories stand on, a grotesque point of view which manages, thanks to an intelligent critique of our society, to make us laugh unendingly, the boundaries of good taste having been left at the door. There is no shame, then, in reading the book and laughing at what poor Yoshio has to go through, as he himself is the creator and the product of the world he inhabits; our main character, indeed, lives in a society that makes him be what he is just as much as he is the main culprit of his misfortunes. He has no real objective in life apart from eating and having sex, without the guilt of believing himself a failure, a useless component of a society which wants us all to be happy, perfect and productive (salaryman, that is). Yoshio “is”, that is, he exists because he was born and because he has to live, lending hear to his biological needs instead of to a supposedly higher calling that neither he has never listened to.

There is a moral compass, of course. Yoshio is a failure, yet this allows him not to pass any judgment on others who dwell in the same social stratum as his. In one of his adventures he meets a gay transvestite, for instance, another element cast off by society, while the fact of being raped by another man, after being drugged, does not seem to bother him at all (different ways of looking at sex, perhaps). Fetishists abound, just like any other kind of person we deem disgusting, either physically and morally, although the overall feeling is, once again, that of a grotesque cour des miracles. There arises, then, the necessity of reading the book for what it is, not for what untrained eyes could see in it: if the stories can sometime shock (once again, the rape scene can produce such a feeling), it should never be forgotten that this is all part of what the concept of grotesque means. If offence is to be taken, then, it is the kind that is due to the canon of the genre, not to the writer being irresponsibly gratuitous.

The end result of Mr Fukutani’s long series is that of making us laugh and, at the same time, of giving us a different point of view from which society (that is, us) should be viewed and analyzed. We are, in other words, not so much that pinnacle of universal perfection, a good job, a good family and a good death; there lurks behind us that feeling that we are, after all, creatures which need food and sex to lead a fruitful life, nothing more, nothing less. Stripped of the vestiges of a universe that wants us dressed smartly, there remains a subterranean world that in its uncorrectedness has a dignity to live.

p.s. : prudish eyes should not open the book. Pornography haters beware!