Creator: Gareth Brookes

Self Made Man, 2021

Before we get to the subject matter of this surprisingly confronting comic, The Dancing Plague, we must first consider some of the marvellous artistic techniques used by its creator, Gareth Brookes. Mr Brookes’ education includes the study of printmaking at the Royal College of Art in London. A definition in the dust cover sleeve describes one of these: “pyrography”, the use of heated tools to create effects in drawings or designs. And indeed, throughout the comic, scorch marks appear, to indicate the presence of the divine or supernatural.

Thus, in a brief digression on the fall of Lucifer and his followers, the paper is slightly burned to indicate the downwards trajectory of the defeated, both angels and devils. And in the climax of the story, a protagonist named Agatha casts herself in a fire, and the drawings of her body and clothes are charred by Mr Brookes’ heated tools. There is no flame. Instead, the scorch marks signify to the read that Agatha is indeed touched by God.

We have never encountered this technique before, least of all in a comic.

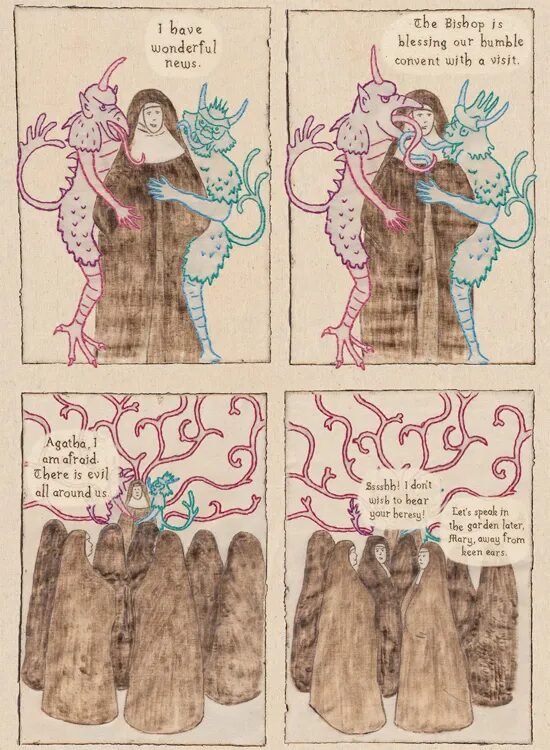

Colour is also a critical aspect of the story. The use of colour in the comic is very restricted. The peasants, soldiers, priests and nuns who inhabit the world of The Dancing Plague are painted in dour hues – no doubt an accurate representation, as the clothing of anyone less than an aristocrat or senior clergy in Medieval Europe would have not been dyed. It is the angels and devils who are in iridescent hues, looking as if they have been plucked from some medieval illuminated manuscript or church stained glass.

The devils in particular are a delight: groping nuns’ breasts and slurping serpentine tongues over faces, with monstrous bodies composite of roosters, lizards, owls, octopi, and other animals. The devils are unnaturally luminous – neon and florescent, not colours which would have been familiar to medieval peasants and which stand in stark contrast to the balance of the art.

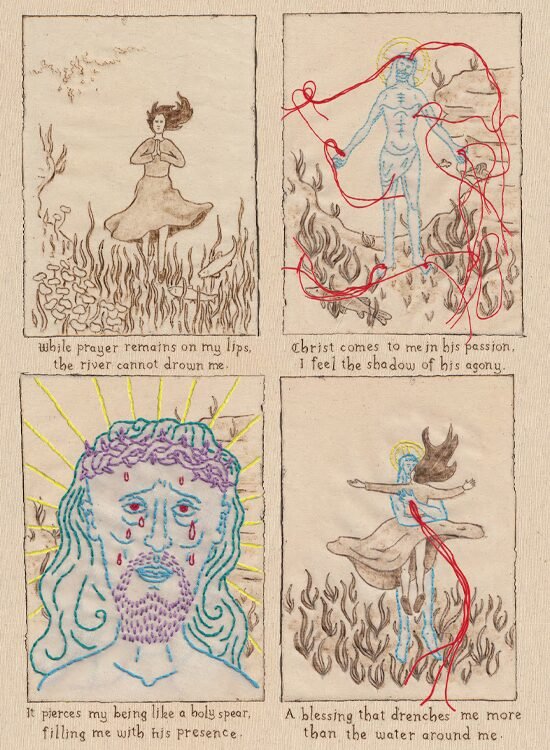

The angels are equally bright but lack the grotesque detail of the devils. Jesus manifests twice in the text, equally radiant. The second appearance is a macabre thing: the severed head of the son of God rains blood from the sky, threatening to fill medieval Strasbourg with bright red blood.

The third technique which Mr Brookes deploys is the use of thread. As milestones of the progression of the story, various pages feature dates. These dates are done by needlepoint, with loose red thread which demonstrate that the dates are not threaded by machine. Crimson thread is laden with religious symbolism – it appears in Genesis 38:37-30, Exodus 26:1, and Joshua 2:18. Scarlet thread in the Judeo-Christian mythos represents holy blood.

And so in one scene we also see Jesus bleeding from the abdomen, with blood spilling down as scarlet thread. This is mixed medium art, conceptually anchored in religious iconography. It is remarkable.

So far we have paid a lot of attention to the mystical aspects of the text. But there is an artificial distinction to be drawn between the daily lives of the denizens of medieval Europe and the supernatural. People of that era saw superstition everywhere, as explanations for sickness, the unusual, the weather. The natural and the supernatural were both real, with only the special able to readily perceive them both. The protagonists in the story are uncanny, and reviled or lauded for it. The story of the dancing plague is well known – see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dancing_plague_of_1518. Here, however, invisible devils (visible to us, and to the likes of Agatha) pull on the limbs of the victims, as if they were puppets, a representation as to how the people of the time must have tried to find cause to the effect. One solution is to pack a town square with all of the victims, and have musicians play in the hope that the effects would eventually wear off. A small girl suffering from the dancing plague is trampled, rescued by her mother, and rounded up again by the city constabulary. The sense of hopelessness is palpable.

Here is the promotional copy:

The Dancing Plague tells a true story, from 1518, when hundreds of inhabitants of Strasbourg were suddenly seized by the strange and unstoppable compulsion to dance, from the imagined perspective of Mary, one of its witnesses. Prone to mystic visions as a child, betrayed in the convent to which she flees, then abused by her loutish husband, Mary endures her life as an oppressed and ultimately scapegoated woman with courage, strength, and inspiring beauty.

An entertaining and helpful introduction is provided by Professor Anthony Bale of Birbeck, University of London.

When we bought The Dancing Plague at a bookshop recently, we expected something more cheery. This is instead a grim story, brilliantly told.