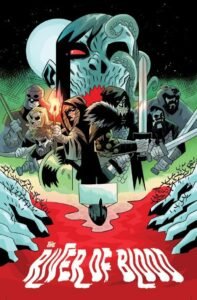

Writers : Carlos Trillo & Eduardo Maicas

Artist : Jordi Bernet

El Jueves (Spain), Página 12 (Argentina) 1992-2005

Prostitution is a concept we usually have quite a few problems with. On the one hand, it is a matter of using another person’s body. On the other we should be ready to state that, if both parties are consenting adults, then there is no real exploitation; let people do what they wish, when no harm is done.

Yet, if behind all this lies a non-existing choice, that is, if the woman or the man is forced to sell their body, then we would be more than right in asking the law to take the matter into its hand and help those who are, in reality, slaves to be freed from such a demeaning situation. It all comes down, who the real agent behind the decision to sell one’s body. If the agent is the seller, and if the decision is taken without there being any pressure or anything similar, where’s the issue, then? A victimless sin, prostitution, in such cases, would need to be accepted by society, as it probably was in ancient (less prudish?) times, just as sexual slavery needs to end and as people should decide for themselves what to do with their own bodies.

The aim of Clara de noche is to present a sex worker under such a light as to make her job be accepted not because of some theoretical inner value, but rather because the person performing this job, the eponymous Clara, does not disowns her role at all. She is, first and foremost, a puta who is also a mother, and in both cases she is one of the best examples of both categories. The end result of all this is that we come to accept her as a person, and a caricature of course. She is not as the butt of our jokes (yes, in case you’re wondering, the pun is intended), but rather as the catalyst to many a short adventure which see, nearly all of them, her carrying out her duties with her customers. Sex is the game, and it is well possible that the series of episodes, to be read once we are mature enough, can be too cartoonishly graphical for some eyes.

It is to be contemplated what kind of characters people Clara’s adventures. Some of the prostitutes are either very cunning or very credulous. Clara herself is portrayed as a strong independent woman who is perhaps one the best mothers in all of human history, as seen by the love and effort she puts in her son’s education (a brief glimpse is what we get, of course, but enough to give us a clear picture). Yet, Clara is also a professional, and sees her situation not as something too dire and desperate, rather as a job she has chosen of her own will. If she is ashamed, sometimes, of what she does to pay the rent, this is due to the fact that society still looks down on prostitution. Here, then, is where writers Carlos Trillo and Eduardo Maicas’ intelligence shine. The people who see Clara’s job as abominable are the same who think she is guilty and to be judged accordingly. There is no idea of salvation, here, of lending a hand so to give the poor woman any kind of respite and what we call a “decent life”.

The customers themselves are seen as driven simply by their own sexual instincts. Yet, the underlying message is not that life is inhabited by brutes. Rather it is that it would be silly not to accept the fact that, in the end, sex is one of the most important factors of any kind of human experience. Each of these men, then, representing every possible kind of lover (we refer to both tastes and physical attitudes), are more than happy to see Clara. Stripped from the necessity to find love as the ultimate source of every action in the cosmos, they are free to pursue a satisfaction that society usually sees as too superficial to be deemed positive. The mercenary structure underlying the physical encounter with Clara is the embodiment of a drive that needs to be given its well deserved culmination only if the price is paid. Again, this being an aseptic transaction – if done between adults who both know what they’re doing – where’s the harm done?

A satirical series of adventures, each one consisting of two pages, Clara de noche is therefore a representation not just of Spain’s caustic sense of humor (a sense of humor not everybody shares in that European peninsula), but also a means to test our own. Having started with a bit of a melancholic attitude, Messrs Trillo and Maicas seem to accept a most carefree point of view after a few panels, a change represented by Jordi Bernet’s style moving away from realism and embracing a lighter sentiment of cartoonish liberty. Some might be offended, for sure. It would not be anything the authors had not thought of when conceiving Clara and her adventures. Let people be free, so seems to be the main idea, free to pay for sex as much as to be paid for if, let us be clear once again, no one is being forced to do so. And, by so doing, let us never forget “castigat mores ridendo”; humans, after all, can be so ridiculous.