Writer: Gary Proudley

Artists: Campbell Whyte, Garry Chaloner, Daniel A. Becker, Stefanie Palladino, Cody Anderson, Lauren Marshall, Sarah Boxall, Louie Joyce, Cristian Roux, Paul Mason, Tatiana Davidson, Al Barrionuevo, Robert Buratti, Jana Hoffmann, Sacha Bryning, Queenie Chan, Brenton McKenna, Dean Rankine, Tim McEwen

Gestalt Comics, 2022

Once again, our paths cross with those of the cunning Talgard. We would not like to meet Talgard in an arena, a battlefield, a dark forest, nor even a tavern. Talgard is not to be messed with. His strategic nature is such that there could never be a social beer with this dark skinned warrior, because Talgard inevitably plays the long game. Even a tankard of brew might lead to a potentially poor outcome. We have met Talgard before, late last year https://worldcomicbookreview.com/2021/10/06/talgard-tome-one-review/ and we are wary of him.

As ever, spoilers abound in this review. Before we come to an analysis of the story, a brief word on the art. A remarkable 19 artists contributed to this second volume. It is a phalanx of Australian artistic talent. Not one of them lets the team down. If we had to single out the champions of this brigade, we pick the power and dynamism of Queenie Chan, Gary Chaloner’s famously clean lines, and Tim McEwan’s vertical perspectives.

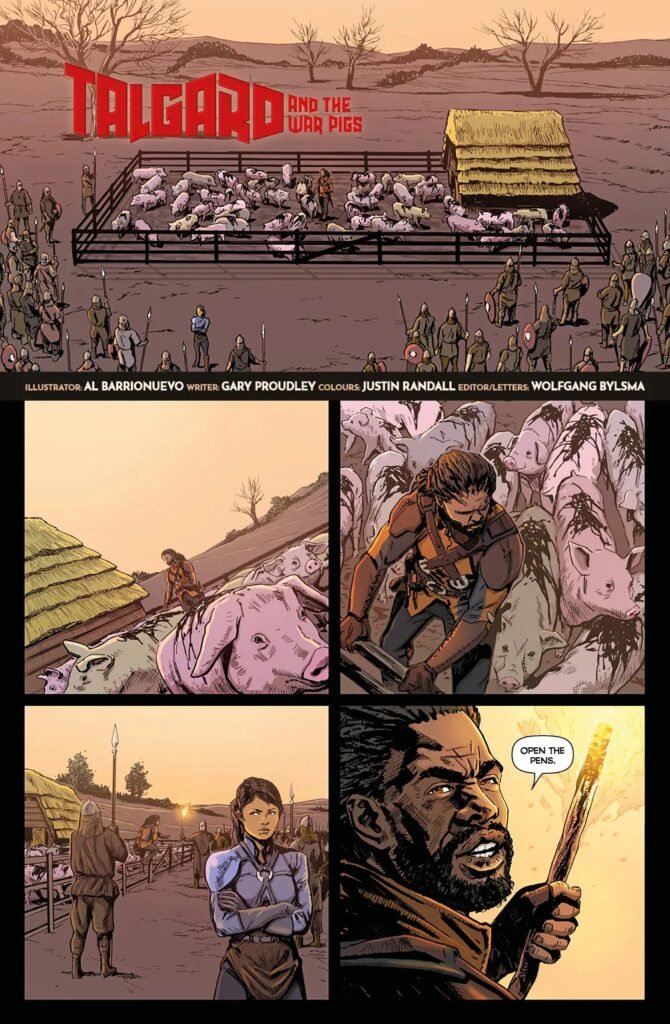

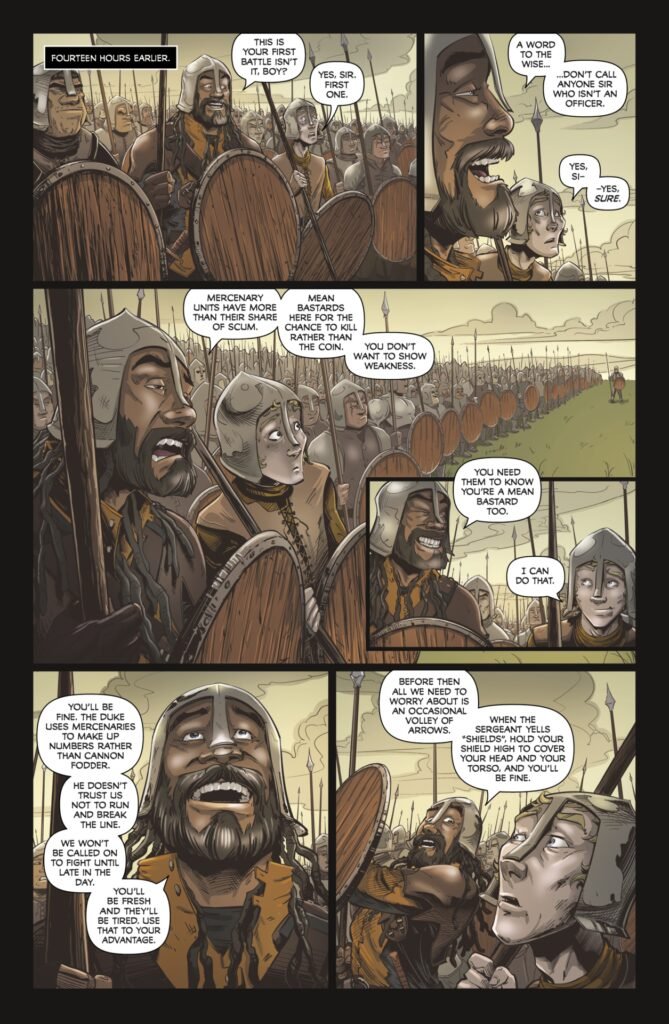

Talgard is a “sellsword”. As fans of fantasy epic Game of Thrones well know, a “sellsword” is a mercenary soldier. (Our efforts to find an archaic etymology of “sellsword” were fruitless.) Talgard sells his services as both a fighter and as a tactician to those who can afford them. And despite in one story uncharacteristically being placed in the role of a mere foot soldier in a rearguard of mercenaries, Talgard is highly regarded across the fictional lands of his universe as a polymath. He is a never-ending font of knowledge of and about the things around him, and he uses this to his advantage. Whether it is birdsong, arcane pharmacology, or doing deals with devils, Talgard always seems to be ahead of the pack. He comes up with out-of-the-box solutions which can even sometimes benefit both himself and his adversaries – they shake hands, and walk away. Talgard’s solutions are not usually out of Conan the Barbarian‘s playbook. In that regard alone, Talgard is quite different from other fantasy texts. Blood and steel are not always the solution.

Talgard has an apprentice named Tydral. We should be used to the idea of women being warrior apprentices after being exposed to the brutal learnings of Arya Stark in Game of Thrones, but Tydral’s role is nonetheless still striking in grim landscapes. She is an ardent student, who sometimes surpasses her master in solutions, and sometimes finds herself mildly punished for not thinking quickly enough. Talgard himself was once an apprentice to a burly man named Recor. In one of the tales, Recor explains that there is a bond between mentor and apprentice which is recognised by everyone in this fantasy world as requiring blood to be spilt if challenged. A proficient swordsman named Yarten ends up with Talgard’s dagger in his face. Yarten has threatened Tydral with revenge after losing to her in a mock duel. The threat has a price.

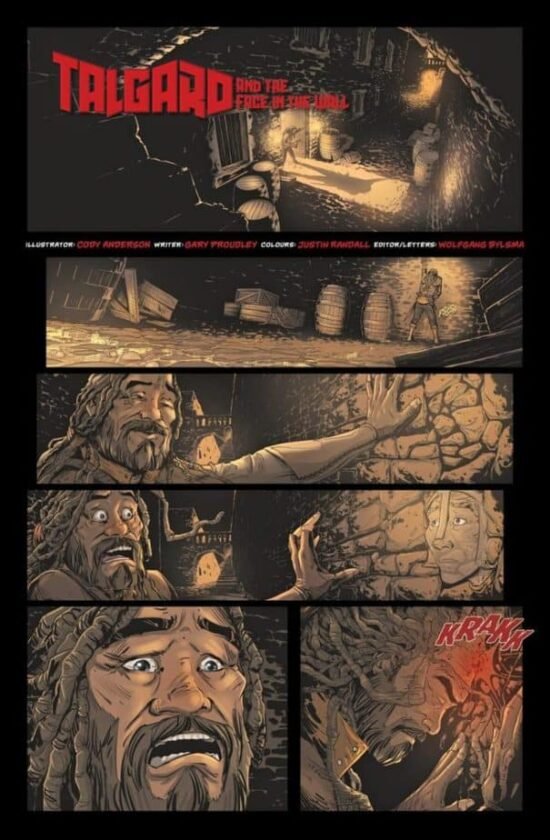

Talgard finds himself in a variety of different situations and dangers ranging from diverting a horde from sacking a city, to helping a pirate escape from an enormous long boat filled with sixty angry soldiers, to some impromptu preventive surgery while relaxing in a tavern. Talgard never fails to repay a debt, nor opportunistically create a debt when the occasion arises. In one of the stories, Talgard is, on the face of it, out to steal a precious stone from a nameless temple’s catacombs. Instead, it evolves that his mission is the freedom of a sentient monster called an ephanisk, which guards the stone. The monster is described as lethal, mercurial, and almost unbeatable. Talgard and Tydral drug the monster into a stupor using exotic vapours, and Talgard then swings an axe to destroy the ephanisk’s chains. He leaves behind the axe, etched with his name, so that the monster knows who has freed him and to whom the monster owes a debt.

On one occasion Talgard punishes himself for being a bad teacher. During a battle, Talgard advises a young man to raise a shield in an effort to stop arrows from hitting him in the head and chest. Talgard is completely despondent when the boy is killed by an arrow strike to the femoral artery of his thigh. Talgard regards competency as a teacher above all other aspects of his character. His failure haunts him. This, too, strikes us as unique characterisation. There is no shrug of the shoulders at the death of a nameless young stranger. The boy has died following Talgard’s advice. Talgard is unforgiving, especially of himself.

Talgard is a character that we may not always like, but whom we certainly must respect. He has a code of honour which isn’t always obvious. Talgard is willing to protect the innocent and will often go out of his way to place himself in danger to that end. Some of his methods are highly questionable. A wizard traps Talgard in a mystical sphere. There is an old man within the sphere who has been held there for a long time, unable to escape. Talgard concludes that the only way he can escape the trap is by human sacrifice. With regret and a promise a vengeance, Talgarth kills the old man. This releases Talgard from the sphere. It seems there was no other way. It underscores the title character’s ruthlessness by necessity. Writer Gary Proudley convinces us early on that Talgard is no hero. But neither is he a villain.

This second volume of Talgard consists of no less than 14 stories (first seen in publication as a web comic). On the face of it, each one of them, as with the first tome, are not related to each other. There is no clear chronology between each of the stories, no common geography, and no common supporting characters other than Recor and Tydral. In some ways, the second major character of the story is the vastly diverse landscape. The term “world-building” is overused by critics, but in this volume alone, we visit the town at the base of the volcano of Syrox, the kingdom of Maruva, the city of Napur and its surrounding farms and rivers, the walled city of Remoscus, the duchy of Entrena, the mines of Mirnbal, and evade a longship from Zernia. It is a diverse and wonderous place, filled with temples, rituals, and historic feuds. We have enjoyed our meagre exploration of it.

But we wonder about Mr Proudley’s own strategy. While we now have over two dozen apparently unconnected tales to contemplate, we are beginning to see early signs of the connected strings on an evidence board, a common plot device of police detective shows. This technique is called link analysis. Why would a dark god offer to enable Talgard to save his friends at the cost of a fraction of his soul? Why did Talgard not inherit his father’s powers of wizardry? Why would another wizard go to the effort of imprisoning Talgard in a pocket universe? What is it, amidst this apparently fragmented dataset, are we missing? Like Talgard himself, we wonder if Mr Proudley is much too clever for his own good.