Writer: William Dumas and community

Illustrator: Rhian Brynjolson

Highwater Press, September 2022

ENTERING THE LAND of the Rocky Cree people in what is now northern Manitoba and Saskatchewan provinces in Canada, and traveling back in time to the mid-1600s to see them, is a difficult journey from here on the Pacific coast living in a freighted metropolis. Yet the scenery of primeval forests and waterways in the newly released graphic book AMŌ’S SAPOTAWAN is familiar. Finding swimmable riverbanks in the Pacific Northwest woods has been a favorite pastime. I can imagine the lake country of the current Métis Nation in the heart of Canada where this book originates must be truly splendid.

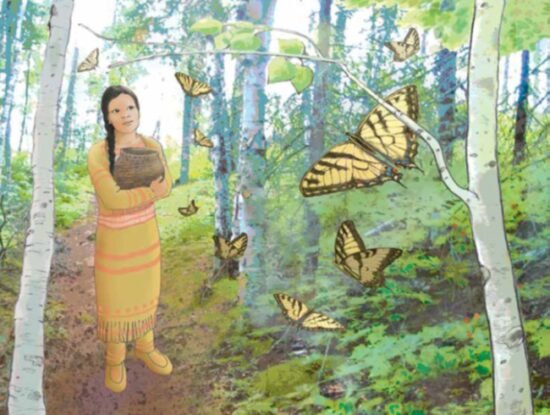

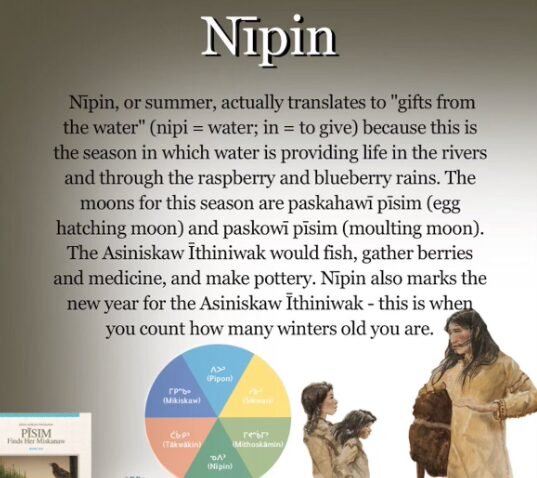

This is an ambitious, gorgeous production, second in a series called “Six Seasons of the Asiniskaw Īthiniwak,” made possible in part by public funding. The season this round is summer, featuring the long days of northern latitudes when temperatures rise from chilly to comfortable, though everyone noticeably still wears long sleeves.

The story by local knowledge keeper William Dumas and many contributors listed in the back, arises out of the ground of the place. The book is dedicated to Brother Lou Dumas, who preserved and shared language and traditions, locations, and artifacts.

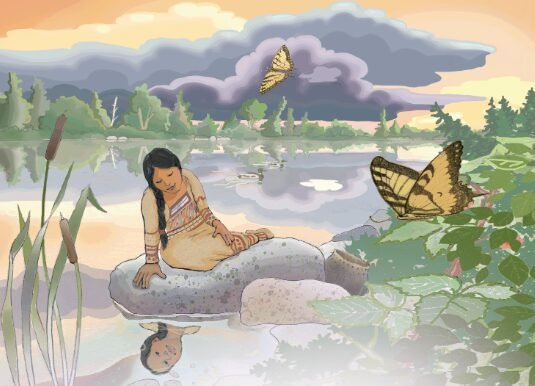

Illustrations by Rhian Brynjolson are crisp and colorful, perfect for a children’s book. Broad art panels fill the space with embedded text to tell a story of an adolescent girl preparing to choose a useful skill as an adult, with some options and role models to choose from.

Sidebars run along the borders throughout with nuggets of technical information to translate native words of the asiniskaw īthiniwak people used in the text, and describe artifacts, and explain customs, beliefs, and practices, including useful information like how to stay still when you suddenly meet a bear in the woods. The graphic design combining story and sidebar information is exceptionally well done, including a broad topographical map on the first inside spread to show exactly where we are.

Engaging, though, was difficult. The whole effort is transparently a vehicle to document and preserve the language and cultural traditions of these depicted ancestors to local people living today, and that purpose seems to get in the way. The story is achingly simple, apparently to make way for the local concepts that need to be explained, and to allow foreign words to be inserted into English sentences as if they belong there, as they would only to someone who speaks both languages. Imagine reading any history this way, even English history. Constant insertions make it difficult to follow. The drama began to feel like a diorama sequence at the local museum with plaques telling viewers what the wooden figures are doing at the moment with an array of authentic artifacts they appear to be using.

The simple story, clear technical bullets, and brilliant design should have locked me in, I was eager for it, and I had to ask myself, “Why not? What age do I have to be to get this?”

Part of an answer arrived when I reflected on the first European explorers in this region of Manitoba, arriving some decades before Amō’s story occurs. They were certainly Frenchmen, paddling the rivers the way the native peoples did, as shown here when the people move their camp to avoid a wildfire. The Cree peoples throughout the region would have heard of these Frenchmen by now for two compelling reasons: the iron axes they sometimes traded, and the powerful mystery of printed words.

Recalling the strong superstitious affect aroused in pre-literate peoples in their early encounters with the written word, here in America and elsewhere, I began to hear Amō’s story in the voice of an old man, maybe my own, casually moving along from point to point in the rhythm of the spoken tongue, sidebars and all. And I got it. Oral presentation may be key to making the material come alive and find it’s natural home.

Some of the gloss on the story raises old philosophy and customs as if they represent ancient and eternal wisdom. I was particularly skeptical of ideas that suggested race characteristics. At one point, the custom of sustainable harvesting is presented like an attribute of the race, attached with religious devotion toward living creatures and their natural habitat, yet these people of the forest from just about this time onward began eager commerce with fur traders, and contributed mightily to the depopulation of the woods from Manitoba to the Pacific of every fur-bearing thing on four feet.

Another point of view on Amō’s beautiful book emerged when I encountered a revised version of a public report I have used frequently over the years in a sharp new format with broad panels and superb sidebars, which I found on closer inspection to be difficult to use. The information was spread too far apart, crossing pages, and not easy to grasp and compare as it was before. Some important parts were missing. I remarked to my academic wife how some researcher evidently got a desktop publishing program and got carried away, and she replied, no, she just had the same issue: they must have contracted out the report to a graphic designer, and when they got it back, the committee could only nod to approve the wonderful job as graphics, whatever reservations might come up about what it was intended to do.

Sometimes the artwork in Amō’s story presents a similar juxtaposition of information and art, aptly, nearly photographic in the backgrounds overlaid by watercolors. The blend of community, knowledge sharers, artists, educators, and public agents in this work makes a landmark addition to a project determined to root itself in the living world today.