Story and Art: Koren Shadmi

Humanoids, October 2019

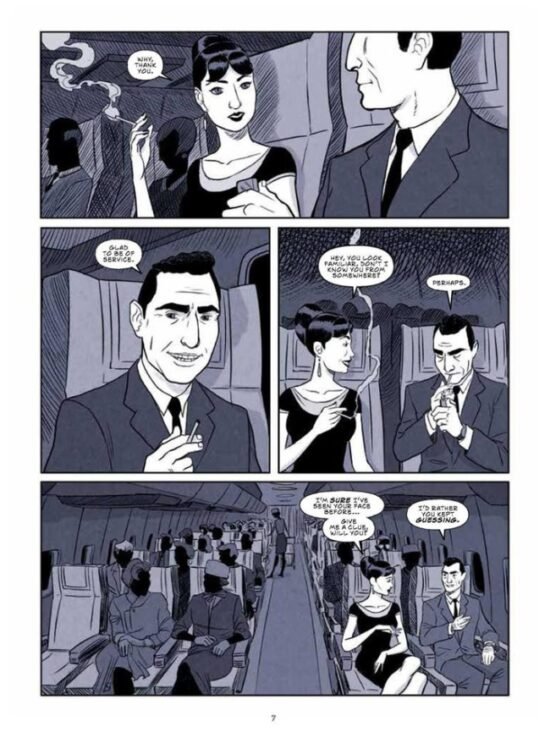

IMAGINE A PASSENGER PLANE in the clouds, located somewhere between departure and destination. Rod Serling sits next to a charming woman eager to hear a story from his life to save her from insomnia and boredom. Reluctantly he gives in. He reaches into his memory and pulls out trains of images from where he started, where he went, and where he ended.

He has time for all of it. It turns out to be a long flight in the twilight zone.

How anyone could pull off this story is a mystery to me, yet author and artist Koren Shadmi in his 2019 graphic biodrama, THE TWILIGHT MAN: ROD SERLING AND THE BIRTH OF TELEVISION manages to replicate the mood and language that made Rod Serling famous for me watching Twilight Zone in the early 1960s. Whatever the episode, I was always most impressed by the couple minutes Rod Serling appeared to introduce it in his marvellously rich voice and expansive language that reached out to, or into a place beyond the conventional universe.

The book is 180 pages, in four parts with an epilogue, followed by a nice art portrait of Rod Serling, an afterword, and a bibliography. In projects like this, one most interesting part is observing the absorption of the creator into the world of the character. The authenticity of the voice and the angles of life portrayed here allow one to appreciate the poignant farewell Koren Shadmi proffers at the end: “… it’s time for me to say a final goodbye to the friend I never knew.”

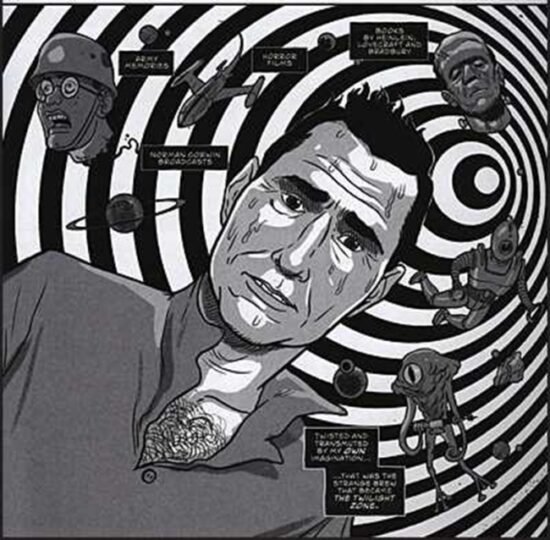

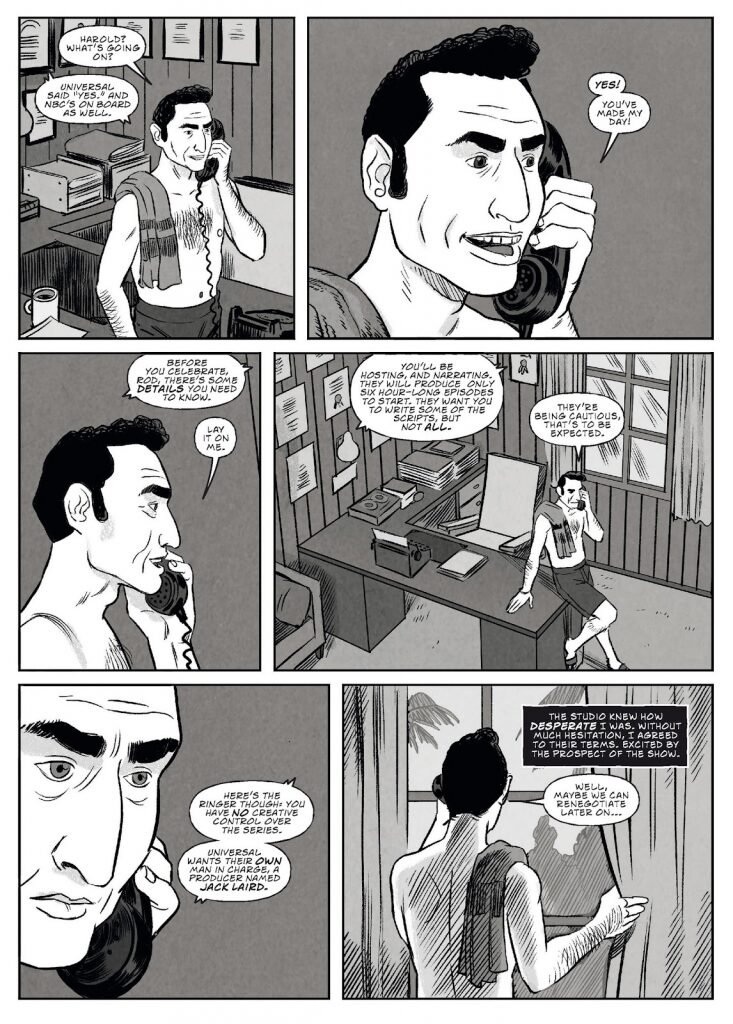

Rod Serling died on June 28, 1975, age 51 (born Dec 25, 1924). His most famous production, Twilight Zone, ran on television one night a week for five seasons, until 1964, in sombre black and white. The graphics here mirror that reality, done entirely in shades of black and gray on a white background, looking quite a bit like images on a television screen.

Part One moves through young Rod Serling’s soldier years, determined to be a paratrooper, though he was deemed to be too short. He persisted and made it through basic training, then moved into the terrifying battles in the Pacific, dropped onto enemy-held islands, all of that, and came home as he summarizes later, to find “myself at loose ends, bitter about everything and at odds with the world.” He was edgy, angry, and had spooky episodes of post-traumatic stress.

In Part Two young Serling uses his veteran benefit to go to college, where he found writing helped him work through the “painful memories of war.” He became manager of the school radio station. A dream come true, he said. There, such as it was, his writing went public.

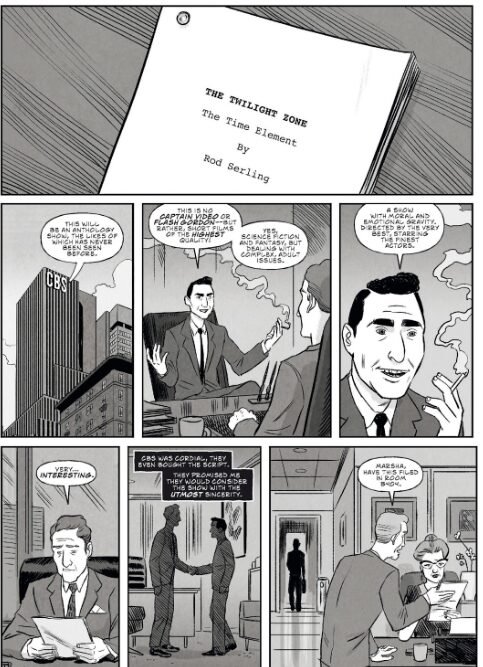

Connecting with the public is a tricky business, especially when bosses have a different idea of what the public wants, or as he found later working in television, what the sponsors want. The amount of rejections and hopeless work stacked up in drawers in between steady gigs constantly grew. Success was perilous: acclamation occasional, aggravation incessant. Twilight Zone emerged as a strategy to sell topical stories related to current issues he wanted to write about by placing them in a science-fiction setting you almost recognize. He managed to elide the censors.

In Part Three, the muse is rolling. This is what we came for. In a frenzy of creation too rapid to write down, he dictated stories into a machine to transcribe later, poured directly from his imagination and the sound of his voice.

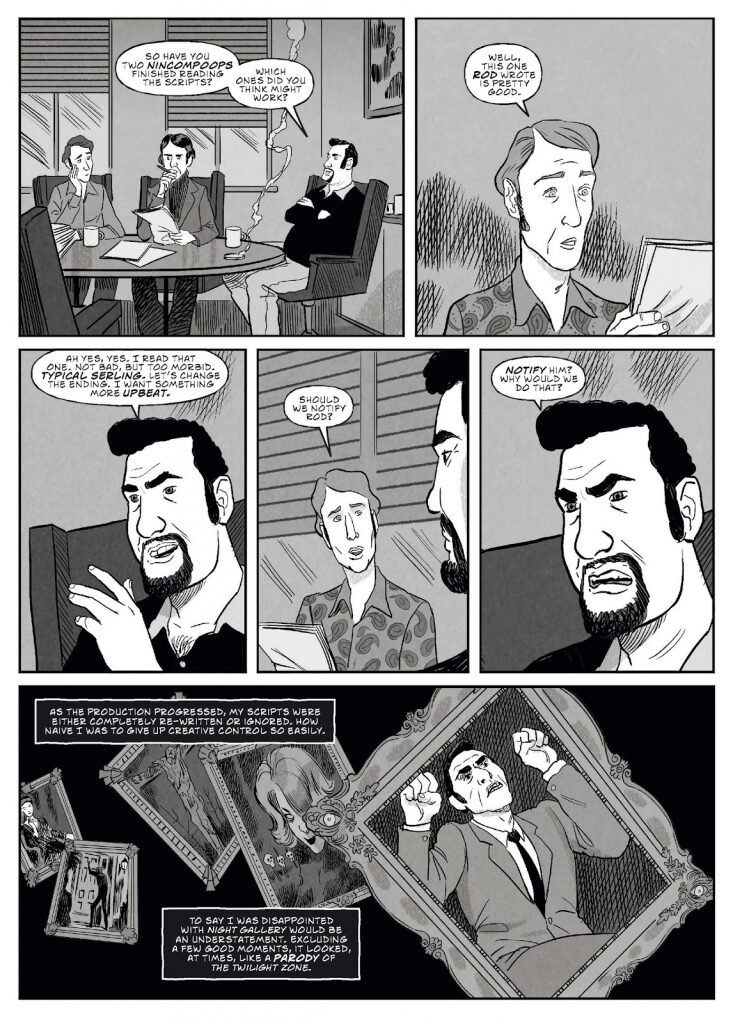

In Part Four, afterward, an older and battered Rod Serling questioned what other directions his life might take, and the spell was broken. He did other things, while other people took charge of his creative work and reshaped it. No results came out the way he intended.

This long plane-ride narration mixed with dialogue and silent graphics is rich in details, twisting through the author’s psyche and spiraling events, pressing the tender parts, and never quite reaching contentment. The pace and polish of the presentation is impressive; the life portrayed rather more jarred and tarnished. In this portrait, it seems Rod Serling was always trying to get somewhere, and the place he found was a cavernous space inside his head crowded with visions. His outer life looks clumsy, his fine self possession a fragile veneer, unfortunate for him and his happiness.

It’s all right, Mr. Serling, one wants to say. No worries. We want you to reach wherever you want to go.