Writer: Rick Remender

Artist: Jerome Opeña

Image Comics, 2017-2021

Over at the AiPT review site, https://aiptcomics.com/2017/02/21/seven-to-eternity-vol-1-review/, critic Ken Petti makes the following observation about Rick Remender and Jerome Opeña’s comic, Seven to Eternity:

“As I think about this book, I can’t help but compare it to Saga, by Brian K. Vaughn and Fiona Staples. In my opinion, I think this book is at or near the same level of excellence. Both stories throw readers into large, complex, actually living worlds. Both stories are about family and responsibility and sacrifice.”

“Family and responsibility and sacrifice”? Seven to Eternity stirs up the ghost of lead character from Steve Donaldson’s classic series The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant. Most stories follow the adventures of heroes, their villains and occasionally anti-heroes. But the lead players in both Mr Donaldson’s six books and Mr Remender’s epic are, instead, weak. Adam Osidis is a disgraced Mosak Knight, an order of sorcerers who have stood up to the villainous God of Whispers and been decimated. Osidis is the story’s protagonist, and the heavy inner monologue, often represented in diary form, is his. Family is an excuse, not a motivation.

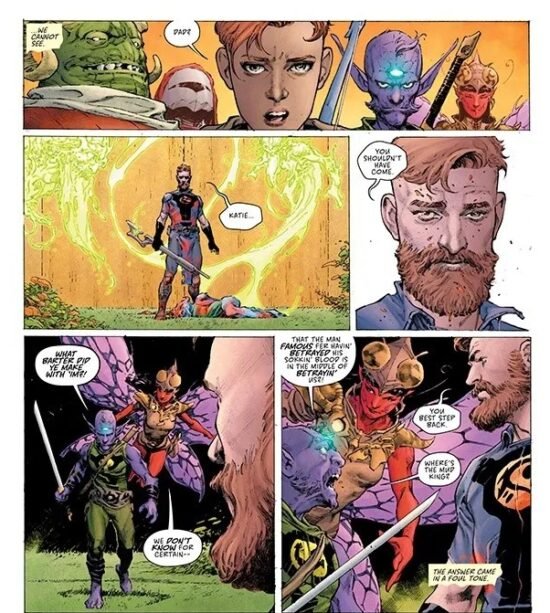

Osidis initially presents as a courageous father who survives against formidable odds, but at the end of the day, he is corruptible. “Family and responsibility and sacrifice” together is a mask to his deep flaws. Osidis presents as almost pious: Mr Opena draws Osidis with hair shorn around the ears, but long on the top and with a full beard: it is not cut through vanity but as an expression of fidelity. Osidis wears his family sigil on his chest, a white dragon, of sorts, on a black background. It has an unhappy history as an emblem of betrayal in the eyes of the remaining Mosak. The stain of his family name never leaves him. As the story progresses, and he engages in betrayal and selfishness, we come to question him in small degrees. Faced with the ability to heal himself from a deadly lung disease, he meets a creature which literally lives in another’s dead and is capable of divining truth from lies. Osidis is faced with a truth: that his motivation in saving the antagonist of the series – the Mud King – is not to save his family, and that he has lied to himself for years.

Osidis’ devoted daughter Katie – who has red hair like her father, is a crack shot with a bow and has an uncanny tracking ability – has disobeyed her father and follows him. As she follows his trail and uncovers his decisions, inexplicably wrong at turns, her sense of disbelief transforms into despair, and, eventually, to resolve.

Osidis’ mask falls away entirely in the final pages of the story. With his family apparently entirely dead, Osidis has partnered with his childhood friend, a winged demon named Jevalia who somehow, chillingly, succumbed to the Mud King as a child. They have produced a Herculean offspring, scarlet and horned like all good bringers of the apocalypse. By that late stage of the story, Osidis has bought into his life as a villain. He has cast aside the facade. And this makes his ultimate fate extraordinarily satisfying.

Christopher Egan at Multiversity Comics http://www.multiversitycomics.com/news-columns/dont-miss-this-seven-to-eternity-by-rick-remender-jerome-opena-matt-hollingsworth/ sees other influences:

“Remender lists famed series like “Dune” and “Lord of the Rings” as direct inspiration for this mashup of sci-fi and fantasy and it shows. There are starships, dynasties, and men destined for the throne while villains sit upon it. With its Western themes, castles, futuristic technology, and bizarre creatures in these ‘blasted lands,’ I can’t help but be directly reminded of Stephen King’s magnum opus, “The Dark Tower.” While he has never been quoted in saying that this book exists because of that series, I can’t imagine it would without it.”

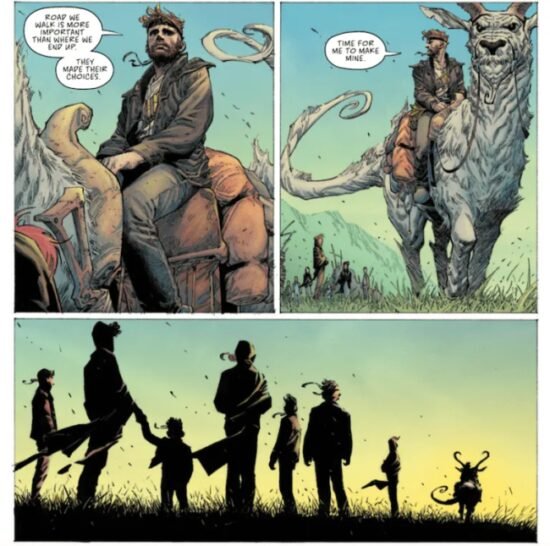

This observation has much merit. Both The Dark Tower and Seven to Eternity are fantastical, desperate quests with strongly Western frontier themes of vengeance, struggle, and redemption. The shadow of famine through failed crop raising on a desolate prairie haunts the characters at the beginning of the story.

But The Dark Tower has the noble and resourceful Gunslinger as a protagonist, and no character like Osidis (nor the equally weak Covenant). Set within the grandeur of vast and exotic backdrops (rendered beautifully by Mr Opeña – more on that below) and more importantly, surrounded by nobler, or better, or stronger souls, their flaws are magnified.

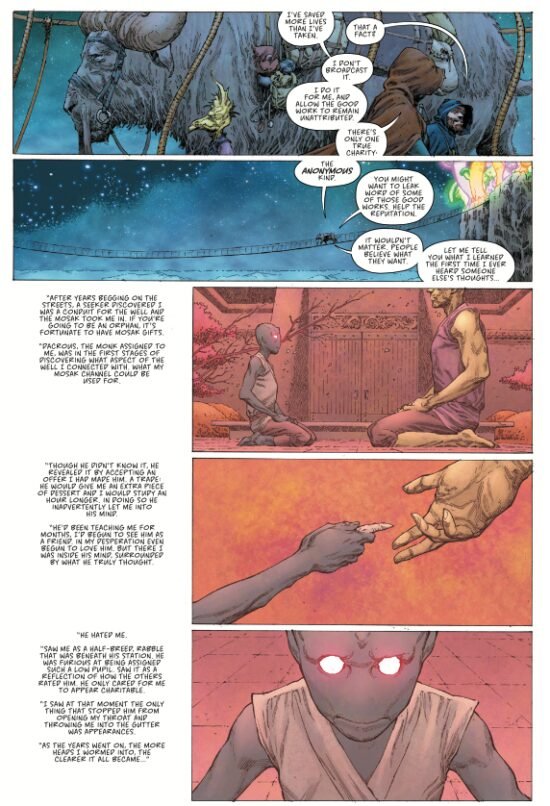

The Seven in Seven to Eternity are chipped away as the tale unfolds. Garils Sulm, also known as the Mud King or the God of Whispers, is the terrible, admirable villain who, even in chains, leads the group. Mr Opeña has designed the Mud King to look like he has been actually carved from mud: a physically intimidating, looming bulk of a figure with clay globs of purple skin, glowing yellow eyes, sitting on a throne of pink skin stretched across bone. He is on a dire journey to prove a point, and get moral satisfaction, in an exercise which costs life after life. But the Seven are oblivious to this – they think they serve the interests of justice. The Seven have against ridiculous odds caught the Mud King, imprisoned him, drag him at great peril through the kingdom of Zhal to judgment… and it evolves that at any time he could have escaped with a flex of his wrists. The God of Whispers does eventually snap his own chains during a mêlée. This causes his captors to finally start to question what precisely is going on.

Osidis is with whom our sympathies initially lie. But it is the Mud King who is the fascinating character. Who cannot sympathise with a man who becomes king so as to not be hurt again? The Mud King’s assumption of power is not motivated by hubris or lust, but by fear and childhood abandonment. Paste Magazine’s reviewer Steve Foxe sees the Mud King as a stand-in for Donald Trump – see https://www.pastemagazine.com/comics/rick-remender/seven-to-eternity/:

“…we’re left to ponder whether Remender is crafting a direct stand-in for Donald Trump or merely a manifestation of the cauldron of anger and fear that led to his troubling ascent. Either way, the series can’t be read without the pall of the previous year and the four… years to come hanging over the high-fantasy narrative...

“As we learn early on through flashbacks focused on Zeb, Adam’s stubborn father, the Mud King rose to power not through brute force, but via his ability to “Whisper” and plant the seeds of distrust and betrayal in the hearts of others while promising the listener whatever she or he desires most. To hear the Mud King’s splendid offer is to join his hive mind and become his willing pawn. Sound familiar?

“Great fantasy often couples escapism with righteous underpinnings: resist the allure of easy solutions, refuse to compromise your morals, never submit to the iron fist of a corrupt leader. As a country, we failed to internalize these lessons. As a protagonist, Adam Osidis may yet succeed. Draw a straight line from Vietnam through two terms of Dubya to the ascent of Trump, and the power of art to affect social change remains as specious as ever. There are, no doubt, readers of Seven to Eternity who will miss even the most obvious political references the book lobs their way.“

An interesting concept but we think this misses the mark and indulges in the politics of the day. The Mud King is charismatic, cunning, and even if he did not have his powers of corruption would have been a formidable player. The God of Whispers is no opportunist con man. If we had to draw a parallel to an American politician, it would be to Teddy Roosevelt: ambitious, mad, and focussed. But, really, it is a long bow to draw to find an analogy between an American politician and a fictional fantasy character who can leech into the souls of those he rules.

The Mud King is, above all, driven. To achieve his objective, the Mud King creates a scenario where his beloved daughter Penelope, trying to rescue him, could be slain? (We as readers do not much sympathise with Penelope – she is a ruthless monster wearing the mask of a creepy doll – but the Mud King grieves for her passing.) Later, he allows himself to be blinded – not an enormous impediment to someone who can see through the eyes of any person who has accepted his bargain, but still, a physical diminishment. Why? The Seven come to realise that the Mud King has his own agenda, and even while he is caged, they are his pawns.

The Mud King’s driver is complicated and perverse. He wishes to to prove to a dead man that no one is beyond corruption. The dead man is a zealot, Zeb Osidis, someone who scorned the Mud King as flawed and beneath him. Zeb is able to determine who has succumbed to the whispered promise of Garils Sulm, and regards those who have as beneath contempt. To prove that point, the Mud King does worse than corrupt Zeb’s son. Instead, he remakes him as his successor, the one who would unleash ultimate destruction upon the world.

Of all the villains we have encountered in the genre of comic books, the Mud King ranks amongst the most complex and the best. This is Othello’s Iago, rendered as a god.

And so we come to admire the admire the villain, yet despise the ostensible hero. That alone is quite a feat of writing.

The other characters are vivid. Drawbridge is a noble monster who dies early and horribly, reduced to a burning and cored out husk, saving the rest of his team of Mosak knights through distraction. The easy defeat of the group’s most physically impressive and perhaps most powerful member at the hands of the Mud King’s son tells the reader that the challenges ahead are impossible to overcome. Another early victim, Patchwork, can be carved up by swords but replaces lost limbs with those of others. The Mud King extracts a fatal vengeance against Patchwork early in the escape. The Goblin is the foil to Osidis, repeatedly challenging Osidis’ self-perception as a victim of circumstance. The pure White Lady, who in a flashback sequence is revealed as having refused to save Osidis’ sick son, is a hypocrite. Dragan is a funny, late addition to the cast – a mercenary who follows the direction of his gold-eating frog who can follow a trail forward through fate towards wealth. Dragon’s appearance at the conclusion provides a sense of inevitability as to Osidis’ doom: here is the wealth, and Dragan is there for it.

Finally, Spiritbox is a looming background character, a disgraced general whose soul is captured in a strange machine which functions as armour. His motivation is simple: he wishes to be released into the well of souls (the afterlife). Spiritbox sees an opportunity to be freed, and the mechanism which has kept his soul from the afterlife is the plot device whereby the swamp-devoured Katie Osidis extracts her revenge. Katie is mourned far too soon by Osidis. As Mr Remender seems to understand, it is the betrayed and abandoned who are most deserving of the gift of retribution.

In Seven to Eternity, Spiritbox is not especially unique in being both dead and alive. The lines between life and death in this comic are blurry. The main cast visit a swamp haunted by the malevolent ghosts of the dead goblin civilisation, killed by the Mud King upon his ascension to power. We also witness the occasional and very compelling appearance of a huge, Lovecraftian creature who catalogues the dead, giving the suggestion that the afterlife is in fact a library. And like all other Mosak knights, Osidis has a special power, in his case, to launch fragments of the souls of his deceased relatives as weapons. This enables the shade of his father, Zeb, to determine whether or not Osidis has indeed listed to the Mud King’s offer, and judge him.

A word on the art in Seven to Eternity. It is not as radical and diverse as the art in Decorum. Instead, it is conventionally pleasing along the lines of a craftsman like Jim Lee or Travis Charest, and a pleasure to look at. Jerome Opena hardly lets the side down. But it is the colours of Matt Hollingsworth which steal the show. Lurid, vibrant, and striking, Seven to Eternity offers a masterclass in colouring.

We rarely acknowledge the work of colourists in the comics we review – an oversight, perhaps – but here it would be completely negligent not to praise Mr Hollingsworth’s work.

The problem for the reader is that it is easy to fall in love with the worlds of Seven to Eternity. Care and innovative thought has gone into its creation and execution. We resent the curtain being drawn across the set. Otherwise, Mr Remender has a technique of slowly building up a story and then allowing the moving pieces to suddenly crash into each other, bringing about a conclusion. Seven to Eternity’s conclusion has nowhere left to go save for an exclamation mark of doom, fire, blood, and familial vengeance. There, like a classic Shakespearean tragedy, the play is done.

(This review is an updated version of a previously published review which contained many substantive errors. Our apologies for those oversights.)