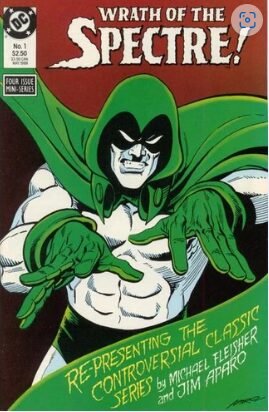

Writer: Michael Fleisher

Artist: Jim Aparo

DC Comics, 1974-1975

Recently, your reviewer has been revisiting stories from his childhood, including Adventure Comics. Adventure Comics was a long-standing depository for a wide variety of minor DC Comics’ characters: Superboy, Supergirl, Starman, Plastic Man, Black Orchid, Aquaman, Deadman, and Dial H for Hero. Its purpose was far from how the major American comic book companies publish superhero stories today. Both DC Comics and Marvel Comics issue a staccato fire of titles, creating a low numbering order so as to encourage new readers to enter the series ostensibly without the need to be across an enormous backstory. Adventure Comics instead pleasantly rambled along for decades. It meandered through completely unrelated tales. In hindsight, there was a lot of variety on offer every month for a mere 25 cents.

Amidst this colourful ensemble of random characters, the Spectre’s tales from Adventure Comics are the best in that character’s long history. The stories were written by Michael Fleisher, with artwork by Jim Aparo.

Mr Fleisher’s writing – both in the plots and the characterisation of the Spectre – was pitiless, ominous, and gruesome. The Spectre was a spirit of vengeance, harnessed to the body of the deceased police detective Jim Corrigan, and in this series the stories accelerated to a terrifying level.

Mr Fleisher applied a formula akin to a medieval cautionary tale. None of the antagonists were traditional superhero villains, but instead were the sort of people a homicide detective with an eye for the weird might encounter (in a comic book context). The Spectre wrecked retribution upon criminal heavies, scammers and Neo-Nazis. But we also see the odd low level supernatural threat dealt with in short and brutal order. The magical threats of the likes of Wotan and Kulak from the 1940s, which might have put the outcome of the story in hypothetical doubt, were gone. Here, the focus was upon the title character’s inherent creepiness and the single-minded nature of the punishment meted out upon mostly low-lives. As Thomas Parker of the Black Gate website concisely notes better than we could – Sadistic Vengeance and Grotesque Death — Still Only 20 Cents! – Black Gate :

In the Spectre’s universe, there is no compassion or forgiveness, and no possibility of reform or redemption; there are no excuses, mitigations, or misunderstandings, and most disturbingly, there are absolutely no limits beyond which punishment cannot decently go. Though he was one of the original members of the Justice Society in the forties, the Spectre never fit in very well with other “superheroes” in any of his incarnations, and least of all in the Fleisher/Aparo version, in which he is less a hero than an inhuman embodiment of insatiable, demonic rage.

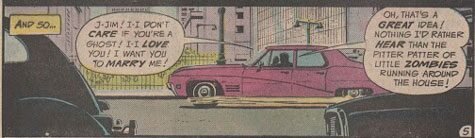

There were some supporting characters – Earl Crawford, a heavyset bespectacled reporter with an uncanny resemblance to Clark Kent (wryly noted by Corrigan in issue #435), and hapless love interest Gwendolyn Stirling. Falling in love with an animated corpse masquerading as a gritty cop was an unfortunate romantic twist for Gwen, and her efforts at trying to improve her position in Adventure Comics #433 led to the henchman of a fake mystic throwing a grenade at Corrigan and Gwen’s close call with a knife. The henchman is dragged into the soil of a graveyard by the dead at the Spectre’s behest, and the Swami is transformed into glass and shatters on the floor. The Spectre transforms back to Corrigan to talk to Gwen about what she has done. “I went to the Swami because I thought that maybe… just maybe… he could help us… help us… Oh Jim, things would be so wonderful if only… if only you were…”

Some critics have been savage in the characterisation of Gwen (not to mention the fact that Gwen was frequently depicted as tied up in nothing but her underwear). But we are more sympathetic. It is a sad and forlorn love, incompatible with the horror of the Spectre’s mission. Corrigan himself is not especially helpful:

If this run of the Spectre’s adventures had been published by DC Comics’ long-missed Vertigo imprint, we might have expected gritty haze and dark colours. This however was the 1970s, and the pages oozed lurid pinks and lime green. Mr Aparo was best known for his very long involvement on Batman comics. His fluid style was ideal for depicting the physicality of acrobatics and fisticuffs.

But here, with the assistance of the shocking colour palette, Mr Aparo made the character purposive and ethereal. The Spectre is on the face of it a ridiculous character to look at: a white corpse in green briefs and a green hooded cape, but Mr Aparo’s depiction of the Spectre’s costume was not at all camp. One of the most striking panels in Adventure Comics #433 is the Spectre rising from a burning car, his form intermingled with smoke and fire. There is a sense of insidious but purposive movement, an unlikely slowness from an artist best known for dynamism. And we are fascinated by the mouth agape – not with gritted superhero teeth – as if the Spectre contemplates both the audacity of what was done to him, and the horror of his own existence:

The best of the stories was published in Adventure Comics #434, an exercise in genuine terror. It is entitled, “The Nightmare Dummies and… the Spectre”. Ezekiel “Zeke” Borosovitch is an old man who sits in a basement handmaking display mannequins in the otherwise modern factory of Monarch Mannequins. Corrigan follows a lead to the factory while investigating inexplicable murders. Some unidentified evil magic enables him to animate the life-sized dolls, and they spontaneously attack innocent people. Zeke describes why in a chilling monologue, a credit to Mr Fleisher’s skill:

“… they might kill if they got angry, and I wouldn’t blame ’em for it, neither! How would you like to go through life the way they do… always on display, no one taking them seriously… No one caring about their feelings!”

Zeke (inevitably) kidnaps Gwen, replacing her with a mannequin which wordlessly tries to stab Corrigan in the back. Corrigan in a blink transforms into the Spectre, and without hesitation carves his attacker up before realising that it is in fact not Gwen who has tried to kill him. Zeke is by the end of the story himself transformed by the Spectre into a mannequin, loses an arm while being unloaded from a truck, and is melted to ash along with other mannequins while unwitting workers stand by a firepit nonchalantly talking about childhood toys. Zeke’s plastic skin drips pink and his mouth is contorted by the heat. Mr Aparo wants to make it clear: Zeke is in hell.

The Spectre’s dismemberment of Gwen’s doppelganger is brutal. The use of the dark red where the mannequin’s limbs were dismembered is graphic horror – a bait and switch by Mr Aparo, where the idle reader is at first unsure as to whether or not it is actually Gwen who was sliced into pieces by the Spectre.

How did this play out with the Comics Code Authority? Older readers will know that the Comics Code Authority (CCA) was a self-regulatory organisation that was created in 1954 by the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA). The CCA was formed as a way for the comic book industry to regulate itself and to avoid government censorship.

The CCA developed a code that outlined standards for the content of comic books, including prohibitions on depictions of violence, sex, and drugs, as well as restrictions on the portrayal of certain types of characters, such as vampires and werewolves. Comic books that adhered to the CCA code could display a seal of approval on their covers.

For many years, the CCA had significant influence over the comic book industry, and publishers who refused to comply with the code risked being boycotted by retailers and parents’ groups. All of DC Comics’ titles bore the CCA seal on their covers. However, the CCA’s power began to wane in the 1970s, as publishers began to create more mature and complex comic books that did not adhere to the strictures of the code. In 2011, the CMAA officially dissolved the Comics Code Authority, noting the organisation’s declining relevance. (The American comic book industry had other things to worry about. It had been very sick throughout the 2000s and many people, including this reviewer, expected at the time that it would be a dead industry by now).

Back in the 1970s, publishers began to experiment with more mature and graphic horror themes, which were not allowed under the strict guidelines of the CCA. Many horror comics in the 1970s were published without the CCA’s seal of approval, which made them less likely to be carried by newsstands and retail stores. Not so Adventure Comics. The seal was on the cover of every issue.

There is nothing suggestive about the way in which the mannequin was butchered by the Spectre, or ow the Spectre melted the flesh of a gunman, or the scissoring of a villain in issue #431. There was no blood, something expressly prohibited by the CCA code. But someone at the CCA was not paying attention.

The readers were however paying close attention. The letters columns towards the end of the run slowly shifted in tone from uncertainty to anger and outrage.

From issue #434:

“… the storyline seemed a bit empty, offering little except sheer brutality. In any medium more literal than comics, the Spectre’s method of dealing with criminals would not be tolerated: here, though, there’s a tendency to get off on the novelty of watching criminals meet immediate, merciless punishment without realising how we would react to the same kind of treatment elsewhere. I’m a bit uneasy about the glorification of this means of fighting crime…”

From issue #438:

“… you have the gall to say that, “… if they have no respect for other’s lives, they have but a fragile claim to their own.” In that case, what is the Spectre doing here? He has, in his present incarnation, no respect for human lives and therefore should be terminated. I’ll be glad when it’s over.”

By the time issue #440 was published, Bob Rodi (later, Robert Rodi, a well-respected American comic book writer on titles like Loki) wrote a letter drolly noting,

“The killing is not objectionable, but it’s losing its effect. I was genuinely chilled by #431… not so anymore. Michael Fleisher is heading towards sensationalism, and there’s something to avoid.”

Another reader (and later a prolific writer for Marvel Comics amongst others), Jo Duffy, was published in the same letter column,

“For all of his supposed status as a superhero, the Spectre is one of the biggest horrors in comics today. The stories never vary, except as variations on a theme. And a grisly them it is. Nasty villain kills a bunch of unmemorable supporting characters in a nasty fashion, and is himself done in by our hero, usually in an equally cold-blooded and horrifying manner…. You’ll never convince me the power behind Spectre is good.”

Despite editor Joe Orlando asserting in the letters column of issue #436 that the Spectre would remain the lead character for Adventure Comics for the foreseeable future, by issue #441 the title’s lead was the much safer Aquaman, and the Spectre was dropped without fanfare.

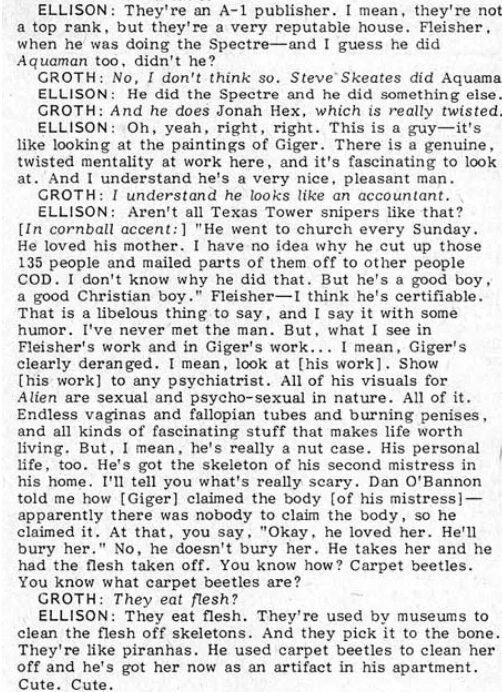

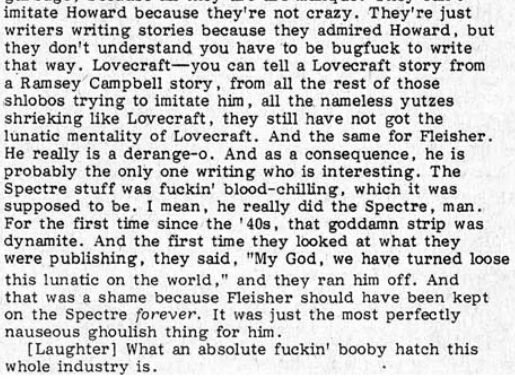

But that was not the end of it. Mr Fleisher’s work on the Spectre in Adventure Comics lead to a libel suit. The famous science fiction writer Harlan Ellison was interviewed by Gary Groth of The Comics Journal five years later, in 1980. The transcript strongly suggests that Mr Ellison was drunk. Here are two excerpts of what Mr Elison said about Mr Fleisher:

The libel trial which followed in Manhattan in 1986 is detailed here: The Insanity Offence: Charles Platt (ansible.uk) . In some jurisdictions before a judge and not a jury, the ordinary imputations of the defamation – that Mr Fleisher was perverted and mentally deranged – would have been clear.

The series, including four unpublished tales (one of which focusses on Crawford, imprisoned in a mental ward for describing his experiences with the Spectre) was collected two years after the libel trial’s conclusion, in 1988, by DC Comics as Wrath of the Spectre!. Times had already changed – and the covers of the collected works did not feature the CCA seal.