Writer: Paul Tobin

Artist: Alberto Alburquerque

Colorist: Mark Englert

Aftershock 2022

A CLEVER STRIDE COURSES through the four-issue mini-series A CALCULATED MAN (2022), inviting you to follow along through little layers of real-life activities of super-smart guy Jack Beans, our hero, sort of, as he pursues his agenda. Scenes shift from Jack doing things, to telling of him doing things from his federal marshal handler in the witness protection program training a replacement, making a little trio of stories, until Jack gets a girlfriend, sort of, and starts telling his doings to her over the phone while she invents her doings to him, making, oh, I can’t keep count. All of them get to know each other or of each other, like pals, sort of.

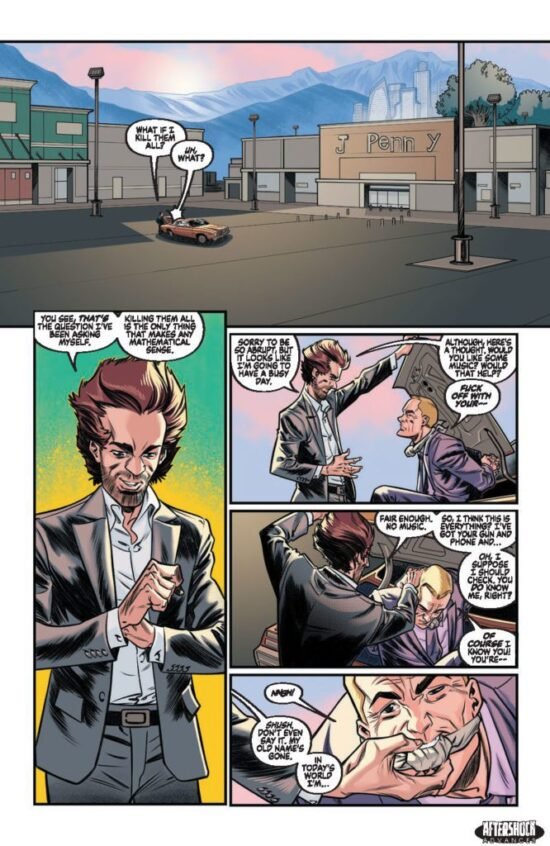

Formerly, Jack worked as an accountant for a crime family, then turned evidence against them, and now needs ongoing protection. Or maybe not. We learn right away Jack already calculated the only solution to his crime-family problem was to kill them all.

Writer Paul Tobin negotiates each of Jack’s targets, alongside a little personal life told by friendly marshal Omaha. Then Jack manages to not tell about himself when he and the marshals meet, though he claims (supposedly) he cannot tell a lie, while at the same time he reveals all when he talks to his girlfriend. Each step fascinates, performed in smooth dialogue with substance and tone.

When the two marshals and Jack get together in a diner in Issue 2, and newcomer marshal Santos grills him to tell her what he is really doing, marshal Omaha, jockeying between them, interrupts to argue to Jack, “Well, math isn’t everything”; to which Jack responds stoutly, waving his finger, “Ooo, I’ll have to beg to differ on that one.”

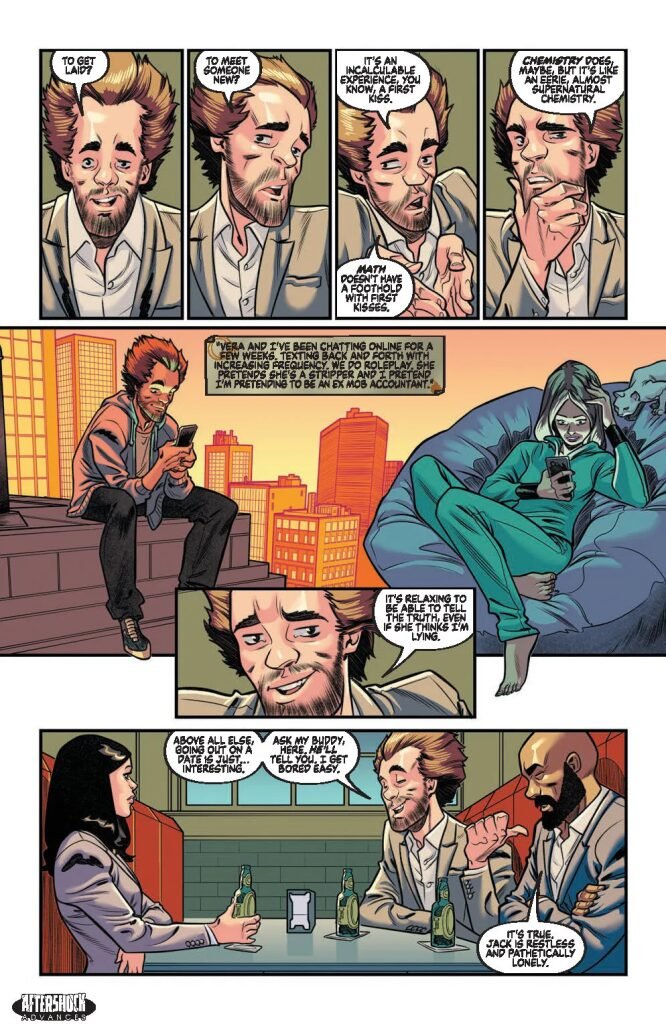

A few minutes later, however, Jack relents, “To meet someone new? It’s an incalculable experience, you know a first kiss. Math doesn’t have a foothold with first kisses.” Even for him, apparently, the surety of calculations have to skirt what he calls “supernatural chemistry.” In the shifting scenes, we get to see some of the chemistry, a cute little romance surrounded by surreptition.

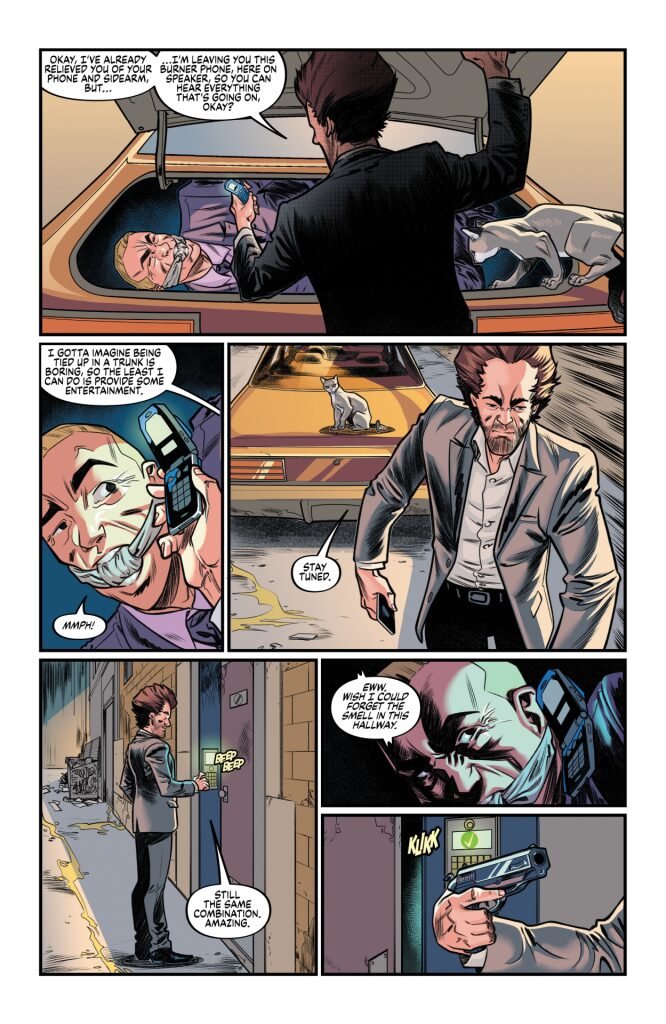

The illustrated lens by artist Alberto Alburquerque and colorist Mark Englert has a dimensional, layered quality of its own that lifts off the page in serrated shapes. Active figures and their contexts slip together neatly, so everything looks real, in place, with a sharp, cartooonish edge.

Likewise, Jack is always calculating his position with deliberate purpose. Maybe from early youth he has moved from one calculated moment to the next in a long arc, as do we all, of course, only Jack has an “uncanny sense of observation and memory,” as marshal Omaha put it, adding substance and precision to his calculations.

Yet there’s more. It’s not a superpower, nor an autistic obsession as we see often dramatized. Jack seems to be a normal person, with a trained and concentrated mind. Midst the weaving story and sharp artwork, the alert consciousness of Jack Beans governing the flow of events around him becomes the central theme, and destination.

I first wanted to say Jack has more consciousness than most people, or is more alert. But neither is right. Others pump up consciousness with all sorts of stuff brim full, look-a-mee. Big and bright is not the same as smart.

In the midst of questioning just what makes the consciousness of the calculated man special, I ran across a remarkable summary of what more consciousness means in the “Findings” section in the back of the current Harper’s Magazine (May 2023), giving a scientific description of the qualities of consciousness that distinguish you and me and Jack Beans:

“Researchers proposed that animal consciousness is neither a binary proposition nor a continuous gradation but an assemblage of qualities: perceptual richness, evaluative richness, evaluative intensity, external synchronic unity, and external diachronic unity; self-synchronic unity, self-diachronic unity, experience of agency, and experience of ownership; reasoning, learning, and abstraction. ‘It is not necessarily worthwhile to ask whether a mouse has more consciousness than an octopus,’ said the lead author of the study.” (p.80)

So—mouse, octopus, kid next door—all equally conscious. How the qualities of consciousness move, interact, and interfere with each other makes the difference. The distances between the colon, commas, semicolons, and period in this quoted paragraph are immense: libraries long.

For Jack Beans, his qualities of mind produce quantities and vectors, probabilities and risks, that results in quick, certain decisions, as when he reaches out to catch a falling wine glass in the midst of a murderous melee. The highest math, evidently, learns to go with the flow. Really, though, no better than a frog on the edge of a pond.

Clever twists and scene shifts breeze all the way through this set, making a packed four issues, dense but aptly intelligible, like a phrase of squiggly figures: (f)xy; lovely if you get it. By the end, newly retired ex-marshal Omaha gets it. Jack Beans gets it. His new girlfriend, the one with the supernatural chemistry, gets it. And … oh, I can’t keep count. But Jack does. Equations resolved.