Writer / artist: Frank Miller

DC Comics, 1983-1984

Critiquing this comic brings your reviewer a deep sense of nostalgia: being baffled by the cost and mysterious subject matter of the first issue sitting in a spinner rack, hesitatingly pulling it out of the rack for a quick flick, and being immediately entranced by the story and the art. Frank Miller’s Ronin was a six-issue comic book limited series published by DC Comics in 1983-1984. The series is known for its then very unique blend of cyberpunk and samurai themes, harnessed by visually stunning art. Ronin was printed on Baxter quality paper stock, expensive and glossy in its day. Each issue contained 48 pages of story and no advertisements. It was far removed from DC Comics’ usual offerings, and was, like Thriller, a precursor to the titles published under DC Comics’ Vertigo imprint.

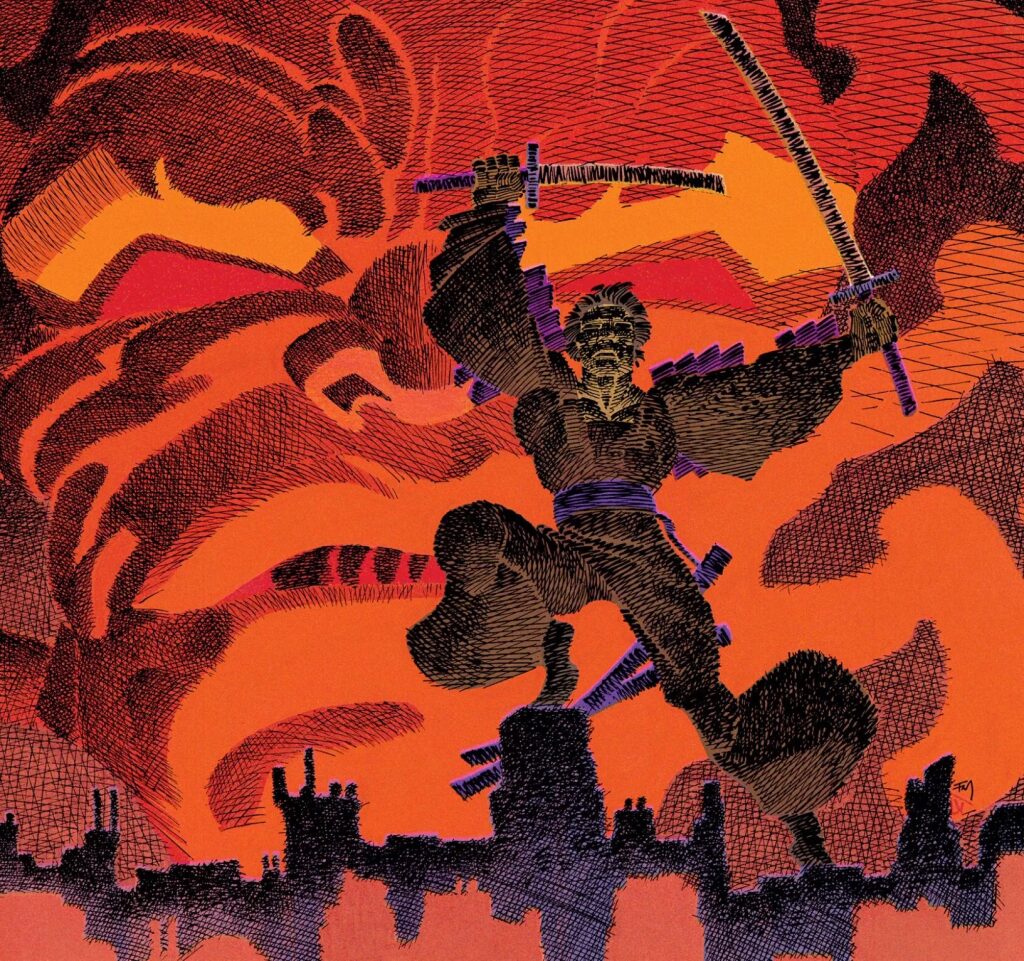

There is a rawness to the storytelling, serrated artistic edges which were buffed out by the time Mr Miller took up his much more famous work, The Dark Knight Returns. Lurid colours and intricately detailed, often meticulously crosshatched art describe the dystopia of Ronin. Mr Miller employs cross-hatching to achieve a gritty and detailed look that complements the futuristic cyberpunk setting. Some of it is strongly reminiscent of the work of Walt Simonson (a friend of Mr Miller’s), but the Wikipedia entry on the title notes that Mr Miller was inspired by the classic samurai story Lone Wolf & Cub. The ronin himself is usually portrayed throughout the series sans the cross-hatching art. It is as if he is cleaner, unsullied by a plastic future.

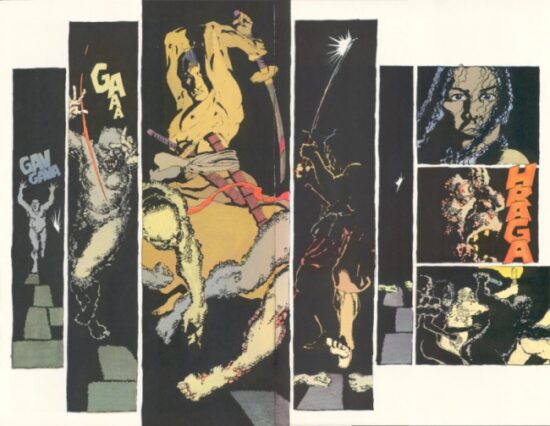

Below is a wonderful scene from the comic. The ronin briefly steps out of the shadows to kill an opponent. The glint of light from the blade of his sword is the only indicator of the ronin’s presence in the first and fourth panels in the sequence. The arcing sweep of blood from his target is the first suggestion of an upward diagonal strike. The ronin briefly appears, and then moves back into the shadow. The backwards movement is plainly indicated by Mr Miller in the ronin’s raised left foot, the brightest object in the panel, with a planted heel. There is no crazy charge forward (unlike his opponents). Instead, there is a lethal patience, precision, tactical awareness. The ronin stands in the inky blackness, waiting, his sword upright and to his right, the glint of the lethal blade the only indicator that he is still there. It is a masterclass in sequential art.

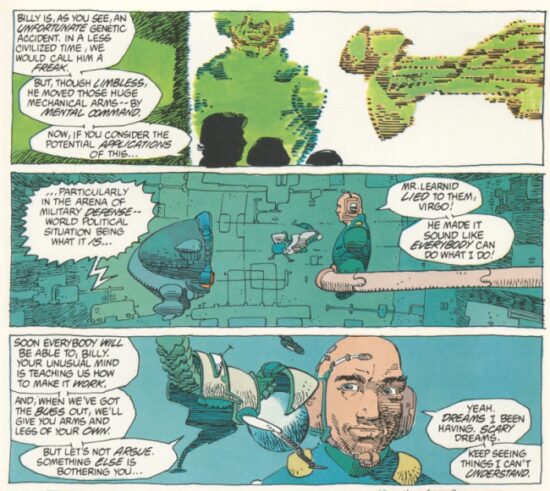

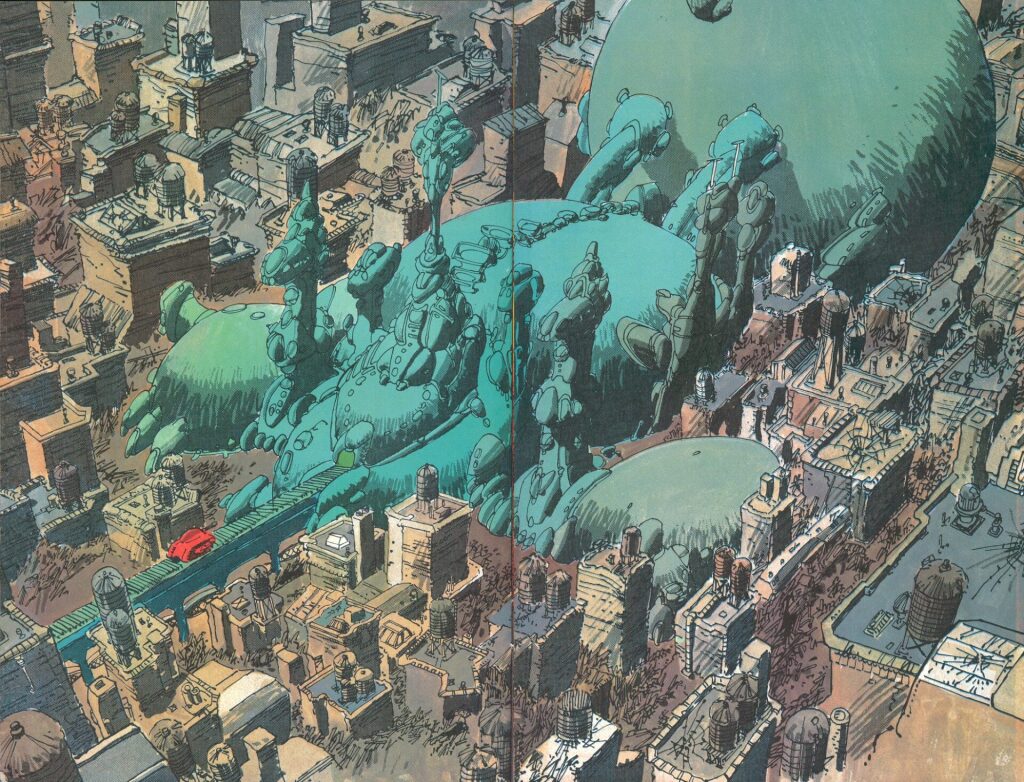

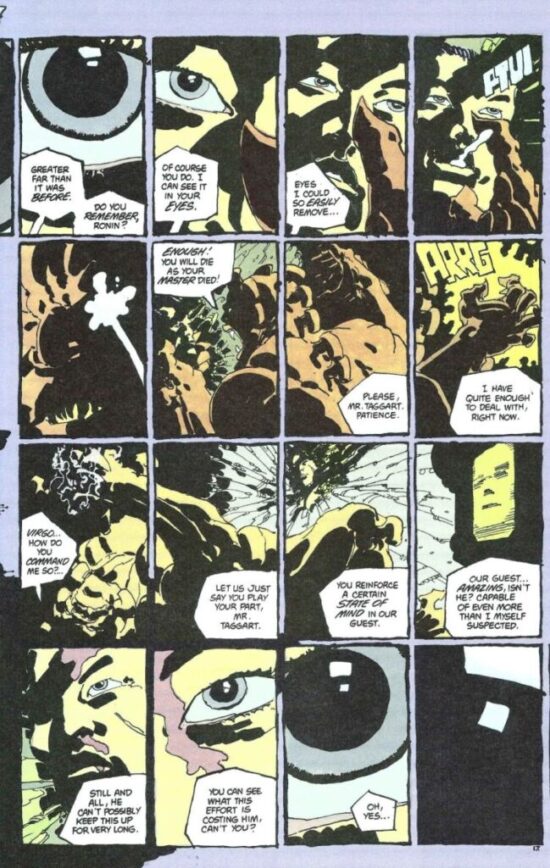

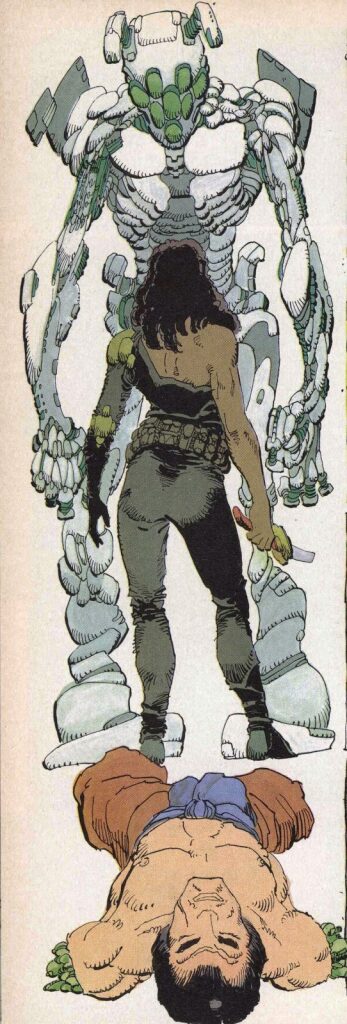

The central character is Billy Challas, a naive telekinetic, lacking arms and legs, exploited by the corporation which manages an enclave called the Aquarius Complex. An omnipresent artificial intelligence named Virgo manages the environs and produces a ubiquitous artificial organic material called biocircuitry. Biocircuitry houses, protects, equips, and keeps occupied the privileged population of technocrats. Green blobs of self-repairing and semi-sentient biocircuitry are everywhere within the Aquarius complex, a symbol of Virgo’s influence over the society.

Some of the unlucky denizens of this world, suffering from horrific skin diseases, live in tunnels and have resorted to cannibalism. Mr Miller was undoubtedly influenced by the Morlocks of HG Wells’ The Time Machine. (The story in some respects could be seen as some sort of prequel to that 1895 novel.)

The appearance of the biocircuitry is symbolically important to the story. The incoherent cannibals might be scared with bubbling and decaying skin, but the residents of the Aquarius Complex are surrounded by its high-tech equivalent: a green and incoherent mass which governs their lives. As the story progresses, the Aquarius complex is shown to expand, like a creeping mould over blighted New York City. The biocircuitry even imbues their clothing. For Billy, it makes up his artificial arms and legs.

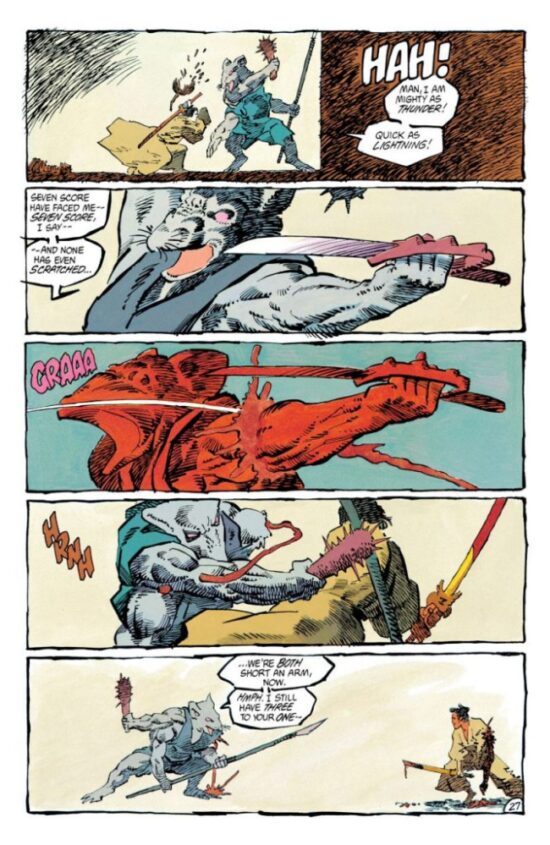

The story itself begins in feudal Japan. There are plenty of nods to Japanese myth and legend. Behold Tesso, the rat monster (see Tesso – Yokai.com ), with four arms and full of pride – at least, for a little while:

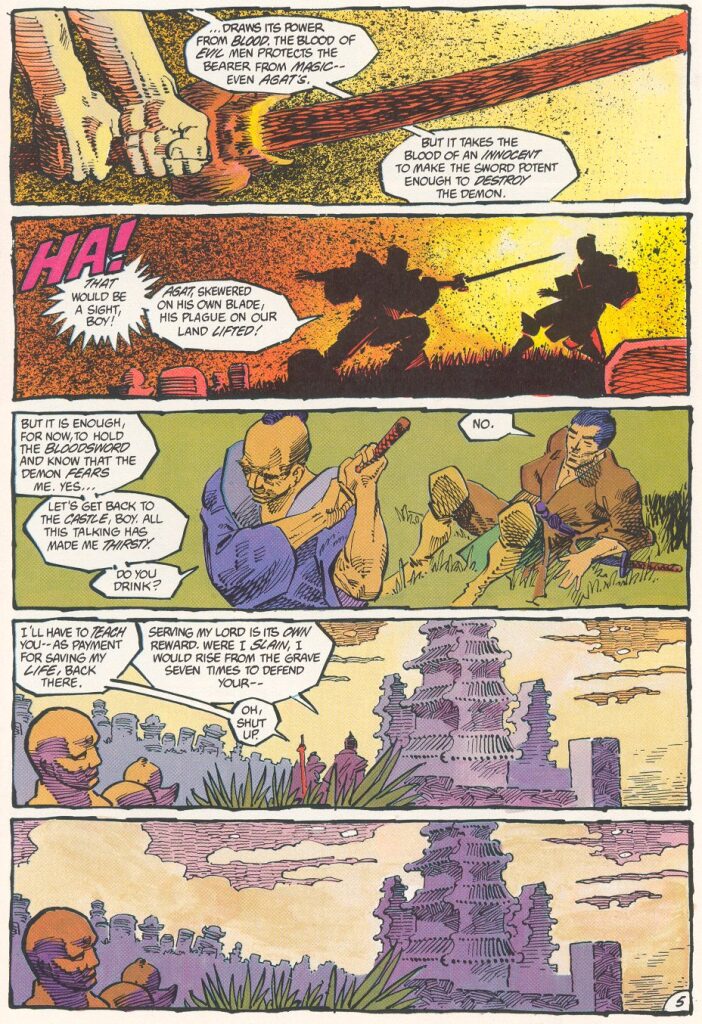

The titular ronin was beholden to a samurai named Lord Ozaki. It is clear that the relationship is new. The ronin is tactically brilliant and saves his master from an ambush, but receives only rough praise for his efforts. Ozaki’s interaction with his apprentice is quite amusing: even though they have not known each other long, Ozaki is already irritated by the ronin’s zealotry:

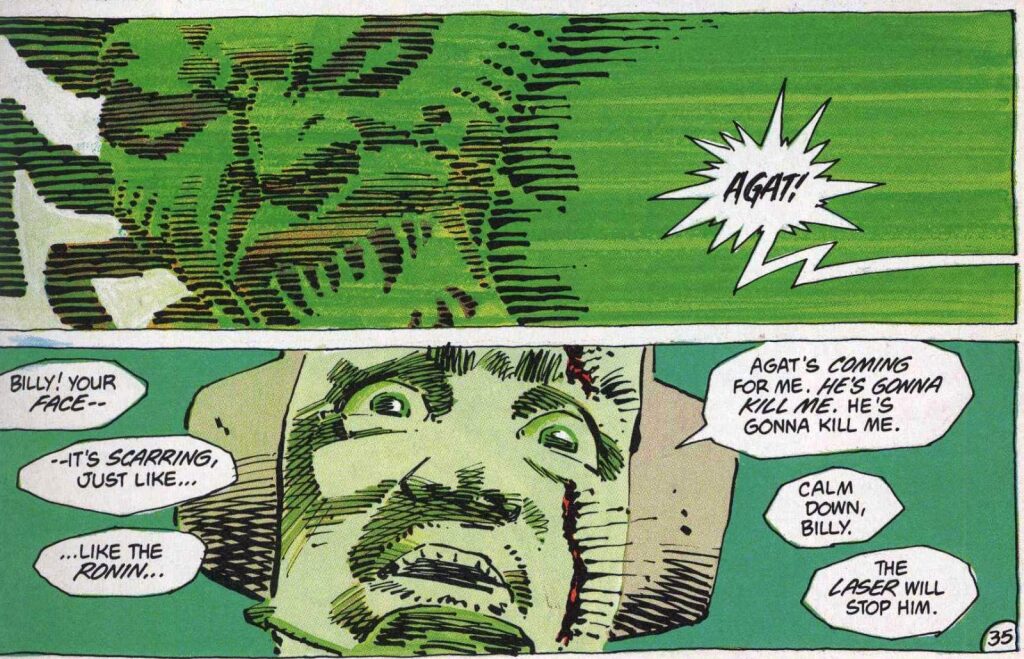

Ozaki dies at the hands of the demon Agat. Agat is a shapeshifter who has taken the form of a prostitute – Ozaki’s temptation has led him to a horrible death. The ronin has failed to stop that from occurring, and so to atone from his shame he goes down the path of a ritual suicide. But the ghost of Ozaki interrupts, telling the young man to skill up and avenge his murder.

Mr Miller does something exceptionally Japanese in recounting the defeat of Agat. Agat can only be murdered once Ozaki’s sword has taken the blood of an innocent. Relentless but not amoral, the ronin will not kill the child of an unwed mother to get through this gateway: blithely, he observes that the child is too small and the mother not innocent enough.

But unlike Ozaki, the ronin’s all-consuming commitment to his vengeance has left him a virgin, innocent of lust. When the moment arises and Agat has the ronin pinned from behind, the ronin skewers himself through his own chest to pierce Agat’s heart. The ronin’s innocent blood is spilt a second before Agat is slain.

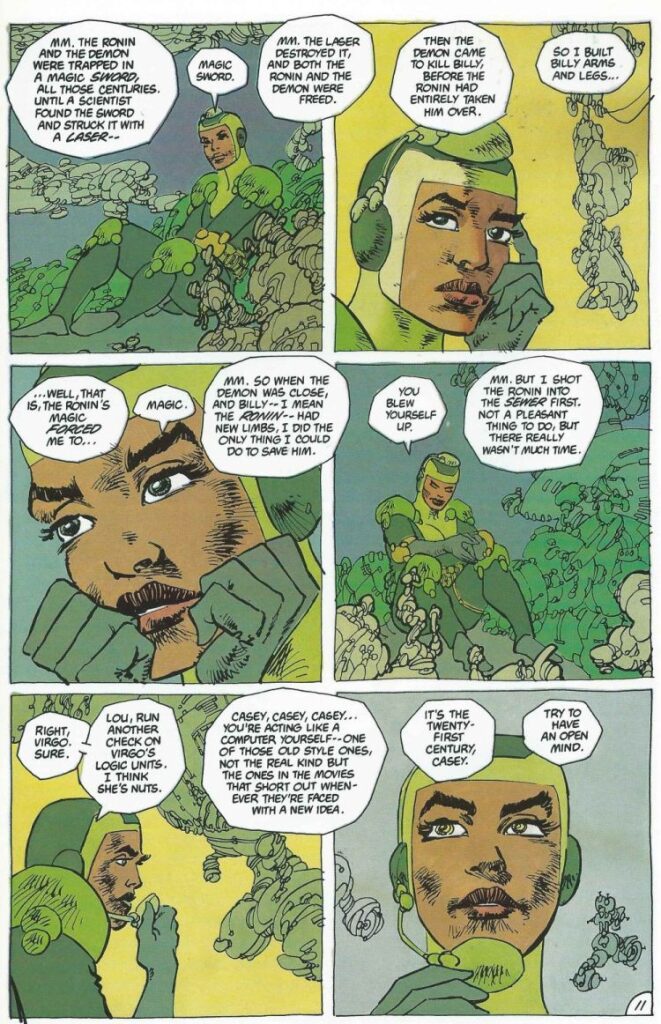

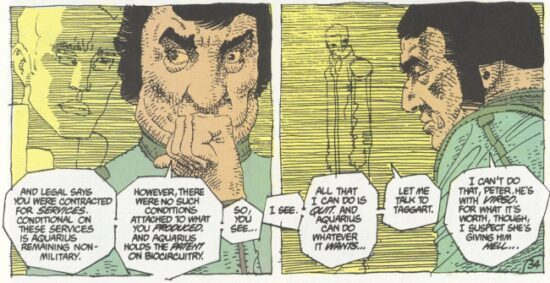

But Agat is not done. He conjures a last spell of reincarnation, which echoes down in time to Billy, Virgo and Aquarius. Agat kills the Aquarius Corporation’s chief executive officer, Taggart, and takes on his form. As Taggart, Agat conducts a weapons deal with the Japan-based Sawa Corporation. The ronin is eventually captured and falls into Agat’s sharp red claws. But, as seen below, where do the spell and Virgo’s machinations begin and end?

Re-reading the story, it is not clear that even Mr Miller knew where it would go at the beginning – magic or science? Ronin seemed to organically grow in strange directions with every new issue. We see that in some of Mr Miller’s experimental art, tested and then discarded, and we see it in the plot. The initial impression is that Billy’s transformation into the ronin is the consequence of Agat’s spell, but somewhere along the way, Mr Miller decided that Virgo was playing a strange game in order to better tap into Billy’s psionic abilities. The conclusion of Ronin in August 1984 coincided with the publication of William Gibson’s groundbreaking novel Neuromancer in July 1984. Neuromancer featured artificial intelligences (Neuromancer and Wintermute) driven by inhuman and almost incomprehensible motives to play a long game with humans as pawns. Intellectual property – specifically, things defined by patents – has become sentient and lethal. No doubt Ronin was at the printing press by the time Neuromancer was released, and but for the tight timing it would make sense if some of Neuromancer spilled over into Ronin.

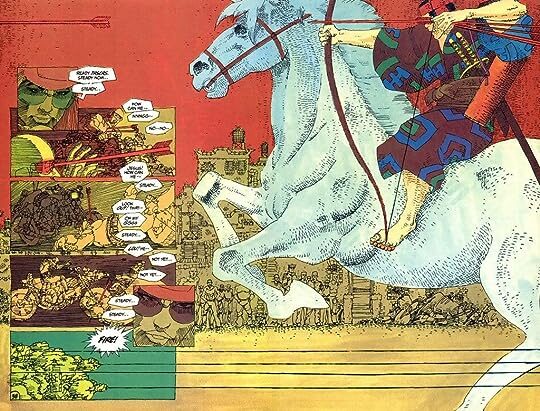

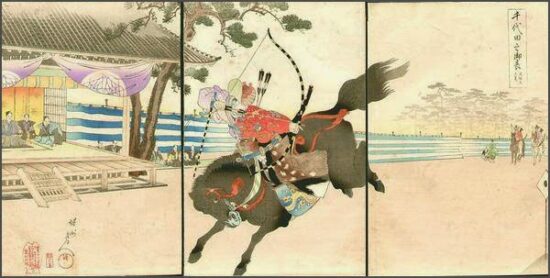

Other influences come from traditional Japanese art. By the time of the publication of Ronin, Mr Miller had already displayed his fascination with Japan (and especially ninjas) in Marvel Comics’ superhero title Daredevil (1981-1983). Below is a comparison of Mr Miller’s detail of the ronin’s charge against the agents of the Aquarius corporation, compared to a classic portrait of a yabusame warrior. Mounted archers on horses engaged in yabusame – see Yabusame – Wikipedia . Mr Miller’s ronin is just as proficient with a bow as he is a sword.

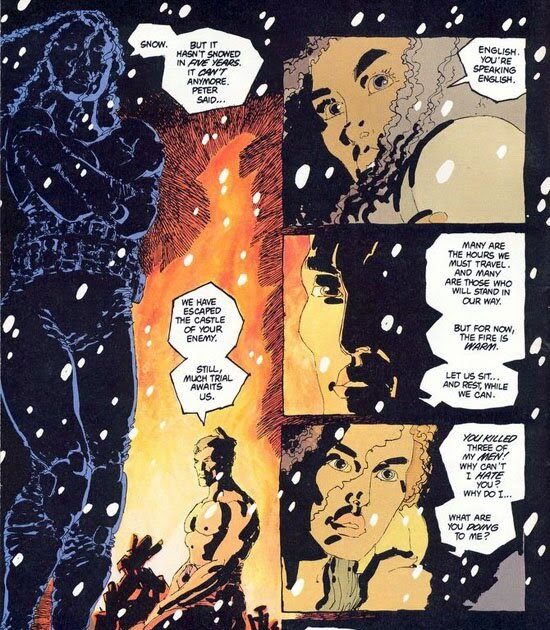

The most likable character in the story is Casey McKenna, the head of Aquarius’ security. Casey is a fearless female character, appearing in a period of American comics notable for finally shrugging off the concept of women as little more than love interests to male protagonists. Mr Miller’s most famous contribution in this regard was the character Elektra, in Daredevil. Mike W. Barr had introduced Katana in Batman and the Outsiders (1983), and writer Chris Claremont and artist Paul Smith recast Storm of the Uncanny X-Men in no-nonsense punk attire (1983). Casey is cut from the same cloth as Storm: a leader, but more soldier than superhero. When the ronin kills three of her men, Casey disobeys orders and tries to kill him to avenge the murder of her charges. Like Storm, Casey changes in her appearance as the title progresses. She shifts from being an urbane security chief in an Aquarius-issue skintight suit to flaunting unkempt, long hair and a charmingly-executed combination of desire and toughness. Billy is in love with Casey and, as the ronin, he drops into a deep hole to rescue her from the clutches of the cannibals. Casey and Billy’s ronin persona develop something quite different between themselves.

But Casey is no smitten female. Casey stares down Virgo when the ronin’s limbs are severed by Virgo’s robot, and she offers to be the ronin’s second when she tells him that if he has the courage, he must suicide for his failure.

Of Ronin, Mr Miller has said, “I want to have a bookshelf of work that lives forever” https://www.deviantart.com/steviestitches/art/Frank-Miller-s-Strong-Female-Heroes-Casey-McKenna-492506332 , beyond the foibles of superhero comics. Mr Miller has this year published a sequel to Ronin. Book 4 of this second series is to be published this month. Here is the promotional copy:

Frank Miller returns to one of his most critically praised and influential body of works, RONIN. This six-part mini-series follows the original work and takes Casey and her newborn son across the ravaged landscape of America. With layouts by Miller, the beautiful panoramic art by Philip Tan and Daniel Henriques captures all the energy and excitement of the original series, taking the characters and world into a direction all its own. Not to be missed!

The problem, though, is that Mr Miller has lost credibility amongst the audience through terribly self-indulgent sequels to The Dark Knight Returns. We presently have no intention of reviewing Mr Miller’s freshly minted sequel. But the excitement of the first series endures. Otanjoobu omedetoo, ronin. Happy birthday, ronin.