Creator: Steven Christie

Independently published, 2018

Once upon a time, your reviewer completed an Arts degree, and was required to read Ways of Seeing. This text was written by John Berger in 1972. It was concerned with how elitism and misogyny pervades the arts and advertising. But for impressionable undergraduates, Ways of Seeing was the trigger for a certain type of pose, especially an extended vocabulary which generated mystification of the arts. Zeitgeist. Brechtian. Nietzchean. Semantic ambiguity. Pastiches. Post-modern deconstruction.

We expect that Steven Christie, the Australian creator of Arrowheads, might have been exposed to a similar counter-pretentiousness. Arrowheads is his parody of it. The promotional copy for this title reads as follows:

Three art school students accidentally find themselves at the mercy of a highly strung curator hellbent on commissioning the next big thing in performance art. Will they succeed in impressing him, while at the same time retaining a sense of sarcastic self awareness? Can they stay cool and avoid becoming part of a “thing”?

ARROWHEADS is a surreal and satirical vision of Melbourne’s contemporary art scene that will feel familiar to anyone who has ever been lured anywhere with the promise of free drinks and hummus. It’s a comic about puffer jackets, pretension, and the power of friendship. Except with Ryan. Nobody wants to be friends with Ryan.

The three main characters are Jules, Stacey, and Sam. There is also Ryan, who is a truly unpleasant individual, and other secondary players. The art itself is simple and often bereft of detail, and Mr Christie uses colour only to highlight characters who are part of a conversation. The figures comprising people in the background are grey, and often look like statutes, accentuated by the fact that much of the action occurs in at galleries. When they enter a conversation, they are lit up in colour, as if a stagehand has swung a spotlight on them.

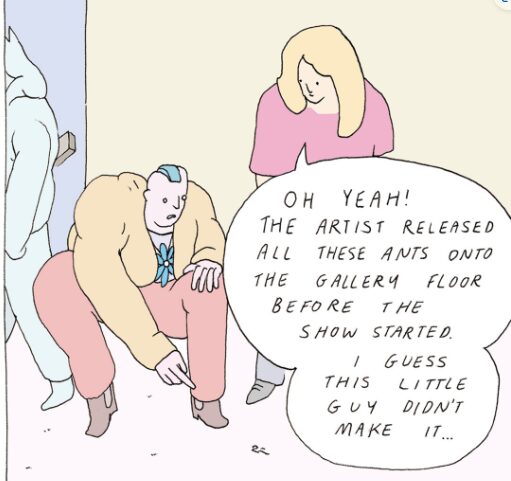

Gallery hopping is part of the scene. The galleries and performance art are contemporary, and as we travel through the story each escalate in terms of ridiculousness. One requires visitors to enter though a manhole cover on the street – it is literally underground. Another, called Permafrost, is in a deep freeze, and features both a snowman and at least one frozen patron. One piece of ongoing performance art consists of a man who decided to get a commerce degree, make money, get happily married and have children. “Actually,” he says, “It’s going to be really had to tell them that this has all been a performance… but that emotion is going to be so raw.” There is an empty plinth, which in its nullity (and possibly telepathic messages, according to Stacey) provokes a profound emotional response: Sam says, with a tear, “It says so much with so little”. (Ryan puts his wine glass and a screwed up piece of paper onto the plinth.)

And there is the vocabulary. Short interactions. Discourse. Cohabitation of the space. “They fluctuate so easily between New New Materialism and a very bold satire. This artist is going places.” What does this even mean?

One of the characters, Jules, eventually has enough. “I’m just done with all the insincerity and bullshit. Can’t we just make things? And not be ironic all the time.” This leads to a rant about how a blank piece of gyprock is just a piece of gyprock. Everyone at the exhibition is appalled. Sam spear-tackles Jules to the ground in order to stop the heresy. Stacey pipes up to save the day: it was, she says, an improvised performance called “The Intruder”. “Thank you for your participation.” The patrons applaud. Stacey tells the talking dog who is the curator of Permafrost that she has merely set the parameters, and perhaps she herself is part of the performance.

In a piece entitled “A Treacherous Art Scene?” for the New York Review https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2013/11/21/treacherous-art-scene/, art critic Julia Bell said of the New York art scene,

You pause for a moment in the fifth-floor lobby. There through the plate glass the Hudson River glitters, framed by converted warehouses, the traffic on the West Side Highway, and, on the far shore, New Jersey in hazy silhouette. Transported, your mind floats free of the business that brought you here. Which gallery did you just step out of? What claim was made on your eyes, and by whom? All is canceled by the bright water. But ping! here’s the elevator you summoned: just time to pocket away the sheet of blather vouchsafed by the snooty graduate behind the desk, before heading out onto the scruffy Chelsea sidewalk to enter some other doorway a few numbers along, ascend to some other postindustrial show-space, go through it all over again.

You—the art critic, that is—might need to remind yourself that properly speaking, it wasn’t mere business that brought you here. It was an obsession, it was romance, something tantamount to faith. At one time, art tugged at your heart, a range of creations that seemed as radiant and self-sufficient as today’s river through the window, yet effected by fellow human beings. For the sake of such magic, you strayed into this marginal, marabout career. And art hasn’t exactly deserted you. Human creativity proves inexhaustibly various: there is forever the prospect of fresh revelations. But to chase after them, you prowl a hunting ground that somehow becomes more alien the longer you remain within. The flashy new art museums, the international art fairs, and above all Chelsea, the district where New York’s major contemporary galleries cluster, seem to hide and deceive: the art world they comprise is a screen behind which art slips away. Too long an immersion in their affectless blather and aggressive cool is bruising to the soul. You want to reach for air. You want to rage and rail.

But Mr Christie does not suffer a pink mist of fury. His glazed-over eyes might be incredulous, but he exhibits no indicia of anger. Instead, the scene and the ethos are to be mocked. “It’s real. I feel it. We all feel it,” says the talking dog.

Eventually, inevitably, the performance art becomes deconstructive. Jules wiggles between a gap in the wall, and defrosts Permafrost. “Fuck you buddy!” she tells the dog. “Shouldn’t have made your gallery out of ice!” And then, “We’re starting an art collective and our gimmick is wrecking shit!”

Bravo, Mr Christie. Let’s hope the art scene forgives you one day. (Unless in reading the comic they become part of the performance.)

The enormously entertaining Arrowheads is available on this link: Arrowheads | Steven Christie (bigcartel.com)