Darkest Rout

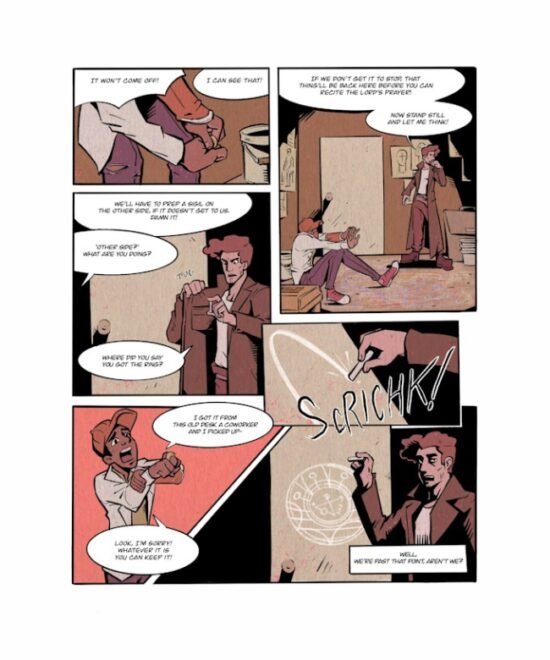

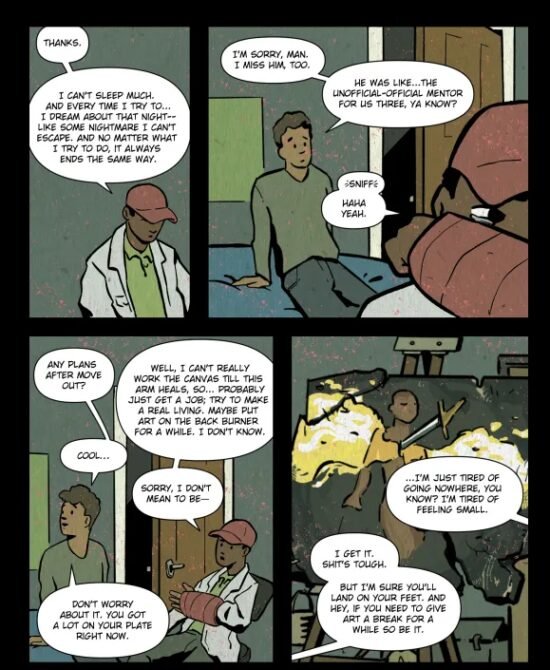

Writer: Antwone Barnes

Artist: Kip Henderson

Independently published, 2023

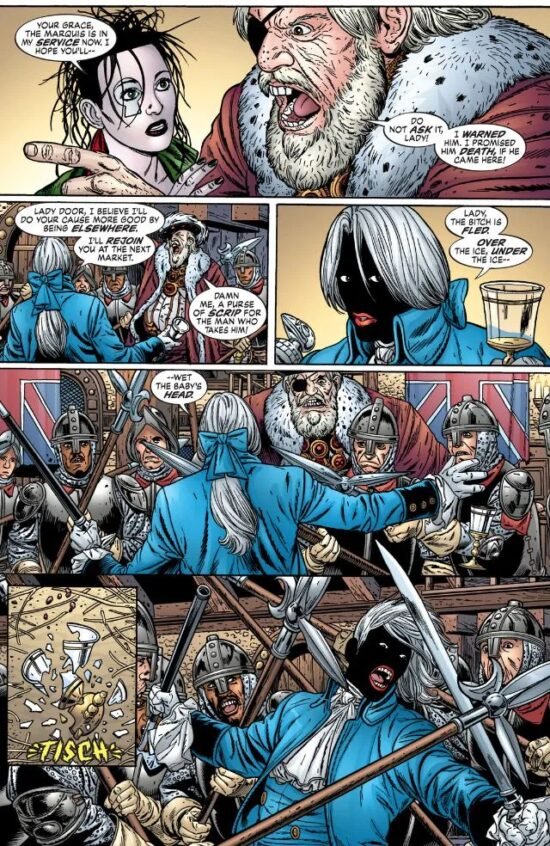

Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere

Writer: Mike Carey

Artist: Glenn Fabry

DC Comics / Vertigo, 2006 (collected work)

This comparative review measures up a freshly-minted independent title, backed by Kickstarter, with a comic-book interpretation of a Neil Gaiman novel, published by American comic book giant DC Comics back in 2006.

The pitch for Darkest Rout is below:

Darkest Rout is about a grief-stricken late-teenage boy from a rundown city who happens across a powerful ancient relic and reluctantly teams up with a self-seeking fallen angel and an audacious occultist to unravel a mysterious threat of demons in the region.

After the loss of his older brother Jonathan, his only family, Nate struggles to find his footing in a rundown city.

At his lowest point, he happens across a powerful ancient relic that thrusts him into the supernatural conflicts between the demonic forces and the “Knights of the Relic”, a secret society of people sworn to protect the realm of mankind, and thwart the forces of evil at large.

With his inexperience working against him, he is compelled to partner with Artewin, a fallen angel working as an “Exorcist-For-Hire”, and Ledesi, an intelligent Occultist, in a race to unravel the sudden mysterious threat of demons opposing them.

It is easy to draw a parallel between the angel Artewin of Darkest Rout and DC Comics’ mystic curmudgeon, John Constantine of Hellblazer. In some ways, Darkest Rout reads like an audition to Karen Berger. Artewin is Virgil to Nate’s Dante, and together they navigate the short-cuts to reality, dodging a wolf / dragon chimera. An artefact – a ring bearing a white cross – which Nate has found in a vintage credenza has bonded itself to Nate. It seems to be the equivalent of a bright flare, attracting the supernatural.

But the compelling aspect to the story is the amount of effort writer Antwone Barnes has put into Nate’s story. Nate is someone who has plainly fallen on hard times. He is a character for whom it is easy to feel sympathetic. Hauling furniture with a cast on his arm is a sure sign of desperation: Nate is a skilled artist who has to pay the bills. Nate has trouble keeping his job. His exasperated boss has a small measure of tolerance left in him, which is ultimately exhausted when Nate trips on his shoelace and destroys the credenza, and Nate is sacked.

Nate is quite a different character from the protagonist of Neverwhere, Richard Mayhew. Mayhew works in the City of London, in a suit, producing reports. He has a boss, who is full of himself and annoying. Mayhew struggles to deal with him: “I call him Mister Stockton, unless he invites me to call him Stock. I don’t laugh at his jokes, unless you tap on your glass.” Mayhew’s girlfriend and colleague Jessica observes, “A little bit of course language is okay. He’ll see it as manly. But not the F word or the C word, and absolutely no smut. But he hates prissiness too.” Mayhew ultimately is weak, bourgeois, and a little useless despite earning enough money to afford an apartment in the City. (Mayhew is only the hero at the end of the day because the mercenary named Hunter, mortally wounded, distracts the terrifying Beast of London so that Mayhew can find an opening with a sacred spear.) Both Nate and Mayhew are depicted generously giving money to the homeless: Mayhew helps the magical aristocrat Lady Door when he sees her bleeding on the street when Jessica just wants to walk by. But Nate is a lot more desperate, and through no fault of his own. Bad luck can befall anyone, and Nate is haunted by the death of his brother to the point of distraction. Mayhew has a good heart, but he only has himself to blame for his soft choices.

Both stories feature angels, but of quite different varieties. Islington is a fallen angel of a particular sort, mad, exiled by Heaven after destroying Atlantis. Artewin is a street smart fallen angel, with his wings cut from his back, whereas Islington is sulking in a chamber at the end of a labyrinth pining for home. Both stories have arcane rules. Darkest Rout‘s Artewin knows the rules, using salt to imprison his nemesis, and a tungsten bullet filled with holy water to kill it. Neverwhere is filled with nothing but rules, spells, and customs: the Floating Market is neutral ground, souls in boxes can be opened by tuning forks, and a key to reality is guarded by devout and loving monks. In many ways, the rules of Neverwhere reminds us of the sovereign citizen movement. Everything is subject to barter and contract, not statute. Favours are like gold. And the fine print matters. “You don’t touch me when I leave. Not for half an hour,” says the Marquis de Carabas, apparently forgetting that there are ways to impede passage without touching.

But the thing which trips up Neverwhere is its inaccessibility to anyone who has not lived in or is otherwise very familiar with London. Knightsbridge is “Nights’ Bridge”, where dark feathered wraiths seize those who travel across to the other side. Earl’s Court is, naturally, ruled by a fat earl. One site of the Floating Market, “Belfast”, is HMS Belfast, a ship permanently moored on the Thames as a floating museum. The Angel Islington, historically named after a long-lost tavern, is now the location of an angel. Downing Street is “Down Street”, and to traverse it one must descend by rope. London above is a thin shadow of what lies below. Mr Gaiman likes to explore the detritus and forgotten histories of places in his homeland of England. But, like James Joyce’s Ulysses, unless you’re in the know, you are lost. Darkest Rout does not require a tourist map to understand. Like Nate, the reader trusts Artewin to take the correct route.

A quick word on the art. It is hard to compete with Glenn Fabry’s experienced and masterful art, backed by a major comic book publisher and its enormous resources. But on Darkest Rout, artist Kip Henderson more than pulls his weight. We particularly enjoy his big, uncanny landscapes (a perfect example of which is below). Mr Henderson’s art reminds us of that of Marc Hempel, a collaborator on Mr Gaiman’s better known comic, The Sandman.

Darkest Rout is available on Amazon, or you can buy directly from the creative team’s site: Darkest Rout