Creator: Adam Suerte

with contributions by Mark Bodē, Sophie Crumb, Myke Maldonado, Jason Mitchell

Urban Folk Art Studios 2022

BODY AS CANVAS goes along with walls as canvas, paper, t‑shirts, anything that takes ink. I was pleased to find artist creator Adam Suerte in BROOKLYN TATTOO, a 150-page bio-graphic of his life as a tattoo artist, through all his ventures, shows, commissions, and pet projects (including this one), also illustrated bathrooms. Rocket cockpits. Much of his time it appears was spent in such caverns as places to dwell and draw, and adorn.

Every panel here is a cavern, densely inked. Years in the making, he tells us, piece by piece. Getting the fit and flow of the story was hardest.

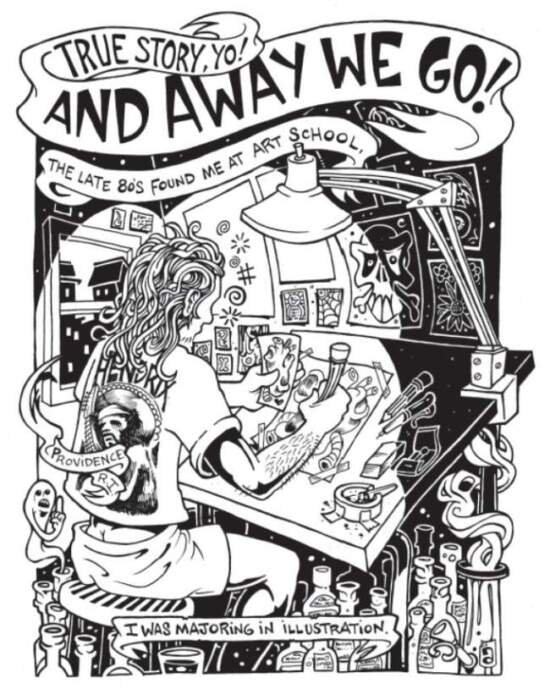

The artist’s life story excels as a document of his times. He begins with a few buddies in the late 1980s in a “big dump of a loft in Bushwick, Brooklyn” with lots of floor space. Add printing equipment, seven years of good times in the local scene, and living to print and paint, and share all around, while the space itself deteriorates.

This sounds like a neighborhood in my hometown, Portland, Oregon, now called the Pearl District, because cheap floor space and negligent landlords in the late 1980s attracted artists like concretions of pearls in the crusty exteriors. The inner city district was a former finishing and merchandising hub, including box companies, metal- and wood workers, printers, furniture depots, and others. When industrial capital fled America to exploit workers in other countries, the place emptied, while venture capital geared up to serve the world’s rich rising on the tide of this global shift. Gentrification loomed. Artists filled the rent gap in between. For the artists themselves, nearby crafts people and resources, and working-class bars made the neighborhood an ideal place to produce, and play. Like Suerte.

Eventually, the artist studio mates find themselves floundering, “doing other people’s shit” just to pay the rent. This is a master theme that nudges Suerte and the others out to new digs and gigs: the enduring struggle to do your own thing, do for others, and also make yourself remuneratively useful doing what you love. Thus, the drift toward tattoo art.

After a year as an apprentice at a newly opened tattoo studio with some killer artists, Suerte is allowed to do his first full piece on his own skin. “It was and still is the most cathartic experience.”

The apprentice period was more like indentured servitude, showing another face of the American age, with its permeable labor conditions. Small business owners have to go with what they got with not much help, and small workers do the same. Suerte grinds his teeth at some of the inequities. This is when he starts writing his comic books to document his experiences. He makes it look like a gas.

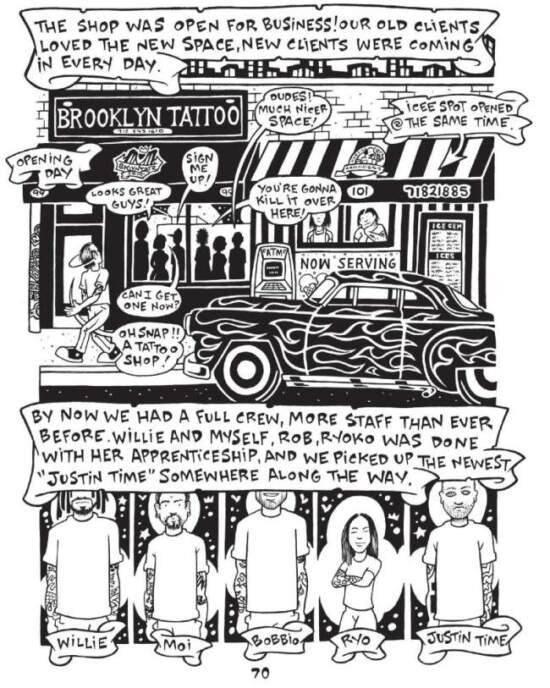

Gotta draw. That’s what it comes down to. The following years take up the bulk of the book. Suerte characterizes each person moving in and out of the scenery in deft strokes, sometimes with little arrows directing attention to details, or little avatars expressing their voices on the matter, or at one point his two toddling kids coming in the room, concerned, as he omnisciently comments on the past from his perch in the future: “Daddy who yu talkeen to?”

Banners, bubbles, and starbursts crowd the graphics in various sizes and shapes, embroidering text inside the action in Suerte’s own stylized lettering. The best way to describe the whole shape of the thing, start to finish, is probably in Suerte’s own words when he characterized one of his early tattoo artist role models: “… he could draw like a motherfuck.”

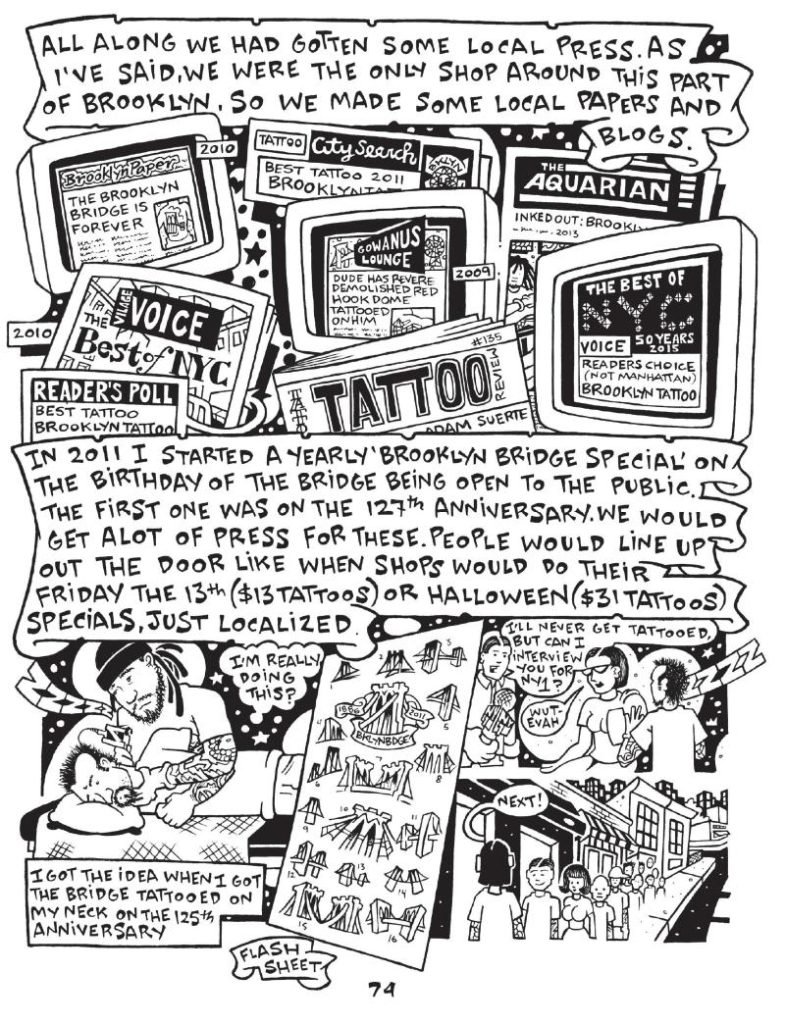

The story hums forward through bumps and bounces, and bright spots in his tattoo and artist studio career, all in a jaunty mood, even bitter parts, handling crackly emblems from the past one can review now with a chuckle. Negative vibes from his later landlord problems, he segregates on black pages, evidently negatives of the original pages. The new age of global capital, and the real-estate state, launched in the 1990s, turned into a vicious story in New York City, where we see Suerte caught in it, like many small business owners and studio artists we all used to know hanging out in the crusty exteriors of our once vibrant inner-city neighborhoods.

The negative pages contrast well with an appended bit by Myke Maldonado, heavily striped with ink so the skin of the paper shimmers through the black, the way a tattoo works. Another appended piece by tattoo apprentice Sophie Crumb reflects the frustration apprentice Suerte sometimes felt when he forgot important details in his meticulous new craft; she jots at the bottom of a sketched page with her new rapidograph pen, “i’m stupid why’d I get a 0.35!? I shoulda got a 0.50 … dumb cunt”—never intended for publication.

Much of Adam Suerte’s artwork was also never intended for publication, or only more or less so. In the aspirations and exhalations of artists, ephemeral art breezes through every generation, every neighborhood, enriching us, as long as we encourage artists in our midst to continue to thrive. Hunt for that panoramic vision nested in a back room, or the bathroom at your local watering hole, secret like, not for everyone. Or maybe, simply roll up your sleeve, or drop your drawers, and say: “Hey Suerte!”

*

NB. Further details on the landlord regime in New York City are admirably exhibited in Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State (2019) by Samuel Stein.

[Editor’s note: negatives of pages mentioned here were a serendipitous fluke that only appeared in the electronic version of Brooklyn Tattoo, not found in the printed version.]