Jonathan Hickman – writer

Valerio Schiti – artist

Marvel Comics, May 2024

This comic was published a few months ago now, but it has placed hooks in our subconscious, and we would like to explore why.

Only last month did we solidly complained about the complete absence of original thought in an ongoing limited series published by Marvel Comics, entitled Avengers: Twilight. An endless recycling of the same set of end-of-history concepts should not be the hallmark of the self-styled House of Ideas. Our review of that title is here: Avengers: Twilight #1 (review) – World Comic Book Review

But G.O.D.S. is a completely different take on Marvel Comics’ characters and where they might go. When Jack Kirby moved from Marvel Comics to DC Comics in 1973, he created The New Gods: a host of good and evil extraterrestrial, super-powered beings locked in an intergenerational war. Mr Kirby had his characters interact with the long-standing panoply of DC Comics’ heroes – Superman, Batman and so on – and thereby expanded the publisher’s universe. In 1987, writer Neil Gaiman went one step further. Mr Gaiman used some existing, obscure concepts from DC Comics’ continuity – notably Destiny, a deliberately mysterious narrator from the 1970s in a hooded cloak with a book chained to his wrist, the red ruby amulet of a second-string Justice League villain called Dr Destiny (no relation to the other guy), and the head of never-quite revealed nightmare creature from the kitsch-y 1970s Kirby comic called The Sandman. From there, Mr Gaiman created a grand, extended tapestry for DC Comics’ continuity, with very adult horror themes, revolving around a family of quintessential avatars called The Endless (the protagonists in a genre-creating title, also called The Sandman). Both Mr Kirby’s and Mr Gaiman’s explorations have been enduring and extremely popular. Mr Gaiman’s story is about to be released in its second season of television on Netflix.

Marvel Comics have just finished publishing a series called G.O.D.S. and we could easily see this, too, heading into television production. The title is a new revisualisation of Marvel’s cosmology, consisting of (as with Mr Gaiman’s The Endless) a hitherto unknown hierarchy of power. The series is deliberately integrated into Marvel’s superhero-heavy continuity. It features stalwart mage Dr Strange, the all-powerful force called The Living Tribunal, and a horror called Oblivion, all of which will be at least passingly familiar to readers of Marvel Comics. In addition, we have several new characters, including Wyn, the 1000-year old avatar of The-Powers-That-Be, and Aiko Maki, a Centivar of The Natural-Order-Of-Things. (Wyn was first seen as a gatecrasher to the X-Men’s Hellfire Gala in 2023.) Each of those hyphenated terms describes “two of the forces that shape all of existence”. Once Wyn and Aiko were married, and now they find themselves each playing for other people’s teams in a hard-to-understand sport. As Plautus noted, “The Gods play with men as balls”. Wyn and Aiko seem at least to know the rules.

Setting down rules, laws, and conventions is the trademark of writer Jonathan Hickman, who Marvel engaged to deliver this project. We are far from alone in becoming very enthused when Mr Hickman is involved in a comic book title. Mr Hickman has deployed his usual categorisation of mystification through order, roles and players. Setting above the The Powers-That-Be and The-Natural-Order-Of-Things are “The Abstracts”, barely explained in G.O.D.S #3: “An Abstract is one of the eight Ur divisors round along the universal axis of power. They are beings of immense power and unfathomable motivation. Greater gods… in every sense of the word.” Each discourse only raises more questions. Mr Hickman is ever the wizard, and we are the acolytes, thirsty for ever more secret, nonsensical, ever-balanced knowledge. We as readers and online speculators are each and all propagators of Mr Hickman’s unknowable conspiracies.

The Living Tribunal has been part of Marvel Comics’ continuity since 1967. As Wikipedia notes, “The Living Tribunal debuted in a storyline called “The Sands of Death” in Strange Tales #157–163 (June–December 1967), giving mystic hero Doctor Strange a limited time to prove Earth is worth saving.” From the beginning, the Living Tribunal is just but not necessarily nice about it, more of an Old Testament God than an avatar of benign justice. In this sixth issue, the Living Tribunal is positively wrathful. The fact that Aiko serves The-Natural-Order-Of-Things, which is aligned somehow on the cosmic matrix as the Tribunal, is the only thing that saves her.

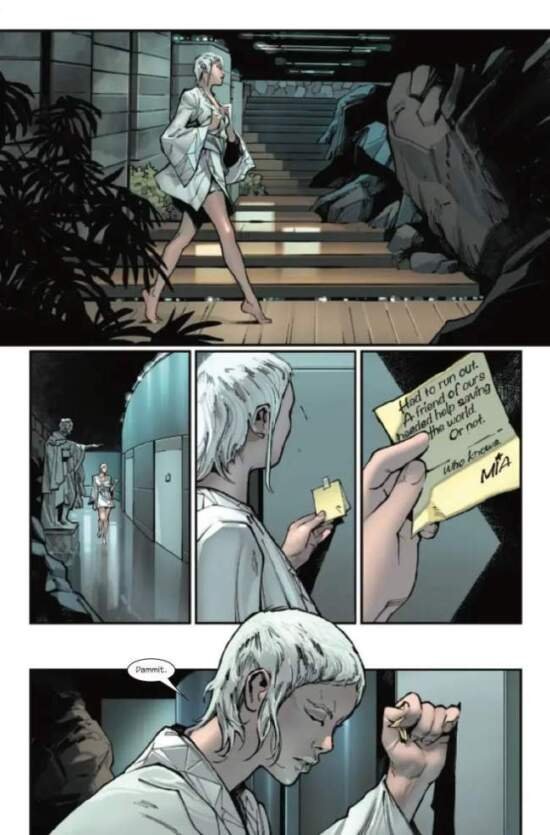

While in other Marvel superhero titles, there is a direct line – some glowing portal or another – to visit the incomprehensible powers which sit up the back of Marvel’s multiverse, here, instead, it is an arduous and mercantile journey. By “mercantile” we mean that there are trades to be had along the way. The pathway is so daunting that Nimue de Lac, an associate of the wizard Merlin (who is probably familiar to comic book readers by way of DC Comics’ classic title Camelot 3000), immediately bows out. She wants nothing of it. Aiko for her part wants to appear before the Tribunal to make a case for the reversal of a brutal decision by Aiko, which has seen Aiko’s protege Mia deprived of access to a life of magic.

First, Aiko and a creature called the Lion of Wolves (her newfound, helpful guide) travel by cart steered by long-horned bulls in Victorian era clothing along streets and through the air to a river. The cost is two gold coins. The driver does not trust the Lion. Aiko, driven by guilt and a sense of duty, does not listen.

On the river sits a boat with the head of Anubis as a figurehead, manned by a skeleton ferryman. The cost: Aiko’s “left eye or nothing but the truth for one turning of the world.” Aiko opts to tell the truth.

The third leg is a key to a third door, where the choice is between a secret no one knows or two of her back teeth. From a high perspective, the reader witnesses Aiko whispering into the ear of an armoured figure. (We are too far away to share in the secret.)

The fourth leg is a flame to light her way through a pit of darkness, where the choice is a smallest taste of blood to a winged demon or the “maiming of an innocent.” Aiko offers blood from her wrist.

The last leg, “the path to the great rock” was “the choice of the loss of one year or her life or the year of a stranger’s”.

Each of the prices seem obvious to choose. But what is the actual cost of feeding a demon with your own blood? What is the cost of the betrayal of trust, revealing a secret not known to anyone? And, it evolves, what complications can arise when you are compelled to tell nothing but the truth for a day?

Having navigated the journey and lead ahead of the queue of supplicants by a being called The Preordained, Aiko makes her case. She does not expect the response. “You think justice is erasing your sin? It is not,” thunders the Tribunal from his mountain throne, as hands made of rocks force Aiko to the ground. It is an awe-inspiring scene rendered by artist Valerio Schiti. The Tribunal is visually hard to comprehend, a floating head of amethyst and gold on top of a giant carapace vaguely resembling the human form. The Preordained rides a golden snake made of prisms, with all of the symbology that image invokes. Aiko is pounded into the stone on her knees, and rendered vulnerable as her clothes are stripped from her. Triangular shards fly around her, with the implicit danger of broken glass. Mr Schiti depicts cosmic grandeur with enormous skill.

Facing the judgment of the Living Tribunal is not where it ends of Aiko. The Tribunal’s shadow brother, Oblivion, makes Aiko a horrible deal: what has been done to Mia will be undone, but Mia will in turn serve Oblivion. Aiko refuses. Oblivion finds her rejection of the deal amusing: it will happen anyway. Aiko is cast away. The Lion of Wolves notes upon Aiko’s return to his side, humiliated and alive only on a whim, that the episode went much better than he expected. The Lion is not being wry, we think. It is instead a statement of fact.

But even then, there is a final price to pay for the guide. The Lion of Wolves has previously explained: “You are bound to each choice as if they were etched in your bones.” Departing from the choice causes “madness [to] set in.” And Aiko has previously agreed to tell nothing but the truth for a day.

This is a conundrum which would have company amongst the Greeks. Giving a left eye to the Ferryman would have been a better deal than being compelled to give both eyes to the Lion of Wolves. The Lion of Wolves is worse than the Sphinx: the Lion puts the impossible choice to Aiko to pull-off a perverted bargain, whereas the Sphinx merely guarded the road to Thebes. But to be fair to the Lion, he did expressly warn Aiko of the consequences of telling the truth for a day.

Perhaps an Orpheus would have chosen to lie, and then held his tongue for a day, not answering any question other than with a smile and thereby neither telling the truth nor lying. Perhaps an Odysseus would have chosen to lie and then cut his own tongue so he could not speak. Perhaps a Hercules would have simply killed the Lion of Wolves.

But as for Aiko, there is none of that: she next appears with bandages over her eyes, lamenting her fate with Wyn. This story is a classic in more than merely the laudatory sense.