Writer: Alan Moore

Artists: JH Williams III, Mick Grey

America’s Best Comics, August 1999 to April 2005

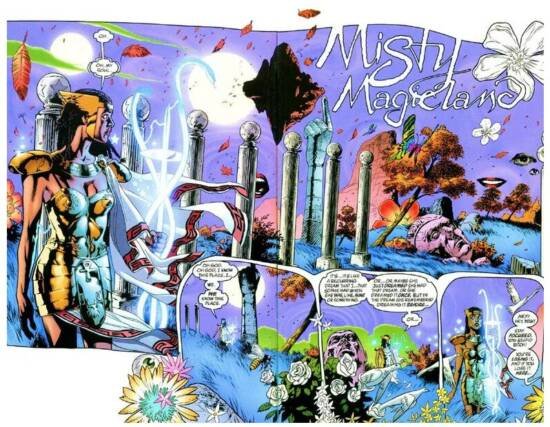

How odd to think that a quarter of a century has passed since Promethea was published by America’s Best Comics / Wildstorm, each nowadays an imprint of DC Comics. The demigoddess Promethea manifests in reality by way a new avatar every quarter of a century or so, and here in 2024 we think the main character, nondescript millennial Sophie Bangs, is probably due to hand over duties to a new Gen Z host.

Long before his falling out with DC Comics, writer Alan Moore was well-known back in the 1980s and 1990/ for his takes on famous superheroes. Mr Moore wrote a beloved story in 1987, “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” which concluded the adventures of the Silver Age characters of Superman. Mr Moore then wrote the definitive Batman story, The Killing Joke, in 1988, in which Batman’s nemesis was seen for the first time in a nadir of perversion. In 1996, Mr Moore re-engineered an iffy Superman pastiche called Supreme with such skill that he was awarded an Eisner for his efforts. Promethea, then, looked at the beginning of the series as if it was going to be another reimagining, this time with DC Comics’ premier female character, Wonder Woman.

The title of the comic could have foreshadowed where Mr Moore was going. Clearly one of Mr Moore’s sources of inspiration of Hélène Cixous’ The Book of Promethea, written in 1983. Ms Cixous is an Algerian-born French feminist critic and theorist, novelist, and playwright. The Book of Promethea is a feminist re-writing of the myth of Prometheus. But it is also a postmodernist work which muddles the identity of the author with the characters. Who writes and who is being written about? Mr Moore took this on board. When Sophie Bangs needs to transform into the mystical goddess Promethea, she writes an incantation in the form of poetry. Bangs becomes Promethea and each of them, student poet and goddess, struggle at times to know where one begins and the other ends. Identity is blurred. Bangs is the fourth version of Promethea revealed to us as readers, the preceding hosts of the goddess all dead, but sitting idly around a scrying pool in another dimension. And again, each of these mirror images of Promethea created across the last century are hazy around the edges, despite having quite distinctive individual personalities.

Ms Cixous wrote within The Book of Promethea, “I am having trouble with this book. But this book has none with itself, and none with Promethea…” Not very far from Mr Moore’s comic book, then. Promethea started off as a popular title, and then its sales diminished as it veered away from superheroics. Hoff Kramer and Winslade in a critique entitled “”The Magic Circus of the Mind”: Alan Moore’s Promethea and the Transformation of Consciousness through Comics” (2010, Graven Images: Religion in Comics and Graphic Novels) offer an explanation:

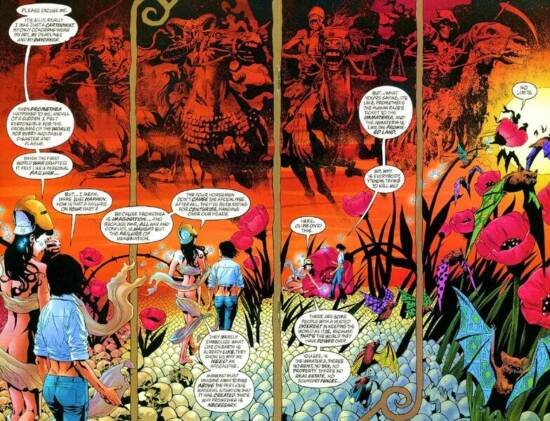

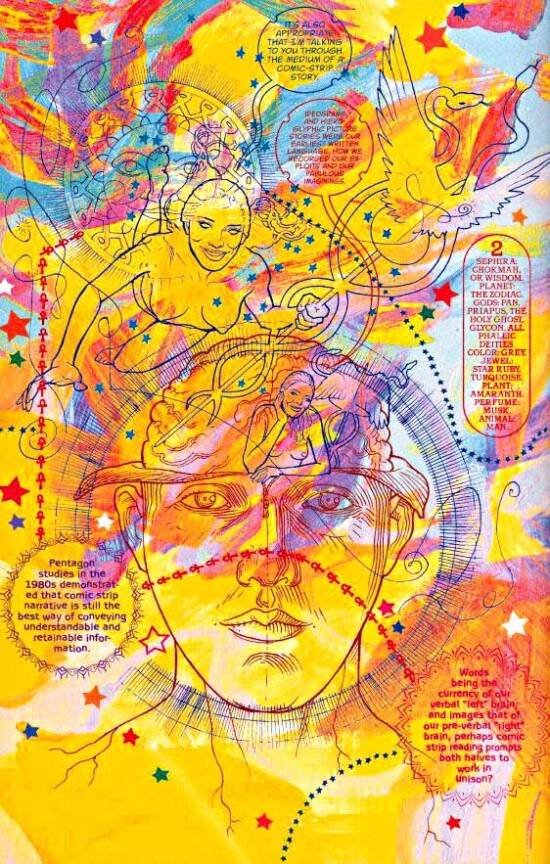

When speaking of the series, Moore concedes that his intention was to draw readers in with a superhero conceit, then use the increasingly esoteric storyline to expose them to the concepts of Western occultism. “It seemed to make sense that we should start at the shallow end, with inflatable arm- bands, so as not to alienate the readership from the very outset (the plan was to wait about twelve issues and then alienate them),” he quips in a 2002 interview. After the twelfth issue of the series, in which the titular heroine makes a journey into the world of Tarot cards (what Moore describes as “probably the most experimental story I have ever done”), it was too late to turn back. Thereafter, the series abandoned any pretense of being a traditional superhero book and took its heroine on a journey through each of the spheres of the kabbalistic Tree of Life, the Hebrew mystical system appropriated by Western occultists. By this point, Promethea had clearly become an outlet for exploring the key concepts of magic and occultism that Moore himself has studied.

The bait-and-switch is not quite true. In the beginning of the story, Mr Moore introduces The Five Swell Guys, who are a tongue-in-cheek version of Marvel Comics’ Fantastic Four. The Five Swell Guys fight epic battles with the homicidal Painted Doll (the Joker, redux) who somehow repeatedly survives death. Mr Moore at the end of the series belatedly returns to the characters: the Painted Doll is revealed to be an army of identical robots created by a rogue member of the Five Swell Guys. In the final months of the title, Mr Moore apparently decided that, having taken his readers on an adventure well outside their comfort zones, he should finish up the unresolved early superhero subplot.

Was Promethea actually an educational adventure, or was it just a beautiful, inaccessible indulgence? Academic Tracee L. Howell posits(1) that Promethea is a Rosetta Stone to understanding the medium:

I argue that Alan Moore’s Promethea is nothing short of compositional alchemy: a radically instructive guide to the graphic medium that takes us on a revelatory exploration of the comic/graphic novel qua magical, imaged-narrative. Read as a whole, the comic series forms a primer that teaches the reader not only how to decipher a culturally-abjectified text, the comic, but by bringing traditional epistemologies into question suggests how readers consciously enact the monstrous, mystical causal dance that Scott McCloud explains is “at work in the spaces between panels.” In this essay I further propose that Promethea may be especially compelling for academic readers, since it performs as literacy narrative by telling the story of a scholar who transforms herself into story. Promethea thus forces the scholarly reader especially to become aware, often uncomfortably so, of that continual process of collaborative narrative construction, and of our own complicity, creative power, and responsibility as empowered.

Promethea was hard to follow at times, but the title’s academic admirers would not be outdone by the text in a contest of mystification. Wouter J. Hanegraaff noted(2) in 2016:

Alan Moore’s Promethea (1999 to 2005) is among the most explicitly “gnostic,” “esoteric,” and “occultist” comics strips ever published. Hailed as a virtuoso performance in the art of comics writing, its intellectual content and the nature of its spiritual message have been neglected by scholars. While the attainment of gnosis is clearly central to Moore’s message, the underlying metaphysics is more congenial to the panentheist perspective of ancient Hermetism than to Gnosticism in its classic typological sense defined by dualism and anti-cosmic pessimism. Most importantly, Promethea is among the most explicit and intellectually sophisticated manifestoes of a significant new religious trend in contemporary popular culture. Its basic assumption is that there is ultimately no difference between imagination and reality, so that the question of whether gods, demons, or other spiritual entities are “real” or just “imaginary” becomes pointless. As a result, the factor of religious belief becomes largely irrelevant, and its place is taken by the factors of personal experience and meaningful practice.

Setting aside the jargon, for those without advanced degrees in semiotics, the philosophy within Promethea could be considered by the reader in segments. It was not necessary to understand the entirety in order to enjoy the entirety. Each facet reflected dazzling light. If it was outside the reader’s ken to appreciate the incandescent whole, that was ok. It was stratospherically highbrow but Mr Moore’s pretension was somehow inclusive, probably by the use of the familiar superhero motifs and inviting dialogue. If the ornate representation of and exposition on the Hermetic Kabbalah was unknown or incomprehensible to the reader, then the caduceus of Hermes, with its two chatty luminous snakes Mike and Mack, speaking in iambic pentameter about the history of humanity represented through a Tarot deck, were there instead. Everyone can take what they wanted. (Even one of Mr Moore’s characters notes – sword in hand – that best-practice problem-solving involves chopping a large problem into smaller pieces. That principle applies to understanding Promethea.)(3)

Some of it, however, seems self-indulgent. Bangs realises early on the title that she needs to better understand what Promethea is about, and so agrees to have tantric sex – as Promethea – with an old wizard named Jack Faust in exchange for knowledge. Some of this comes out as a diatribe mid-coitus, but Bangs is left at the end feeling awkward and embarrassed to have hooked up with a man old enough to be her grandfather. Faust tells Bangs to go read some books and kisses her on the forehead. Mr Moore is a self-described wizard and he and Faust wear similar rings. Mr Moore might have said he was metaphysically coupling with his creation. Regardless, it is cringeworthy to read.

Missing from the story is any idea as to who might have predated the earliest, World War One version of Promethea. Promethea begins when a little girl in Alexandria runs into the desert in 411BC, her father having been stoned to death by a mob. The god Thoth-Hermes brings her into the Immateria. But who were the hosts of Promethea prior to 1914? Was Britannia, with her trident and dolphins, a representation of Promethea? Or Marianne, the barechested icon of the French Revolution? Regrettably the series is done, and we have no opportunity to delve into Promethea’s earlier past.

As we have previously reported https://www.worldcomicbookreview.com/2018/02/22/exhuming-promethea-authority-dark-knights-wild-hunt-1-v-justice-league-24-comparative-review/in January 2018, DC Comics made the ignorant editorial decision to introduce Promethea into its mainstream continuity, appearing in Justice League of America #24. Promethea’s artist J.H. Williams III was famously quoted as saying: “I can’t in good conscience condone this happening in any form at all”. DC Comics chose to depict the early version of Promethea in its superhero story, not the later version where, clad in crimson and as the Whore of Babylon, has brought a benign apocalypse to the Earth. But why use the character at all? Promethea’s walk through occult philosophy within the Immateria (a dream dimension of imagination) was educational in its purpose, and clearly a labour of love for Mr Moore. Promethea’s vapid appearance in a mainstream superhero comic seemed to be a snoot at the man who had famously turned his back on DC Comics, tired of the publisher’s cavalier behaviour.

A better collaborator to Mr Moore than JH Williams III would have been hard to find. Mr Williams’ art is breathtaking. The impact of Promethea would have been reduced if in the hands of a lesser artist. As Hoff Kramer and Winslade note:

To take advantage of the complexities made possible by the comics medium, Moore and artist JH Williams use, unusual page layouts and juxtapositions between text and images to capture the mood of Sophie/ Promethea’s psychedelic travels in the Immateria, the realm of the imagination. Panel borders curve, turn wavy, or melt entirely; other panels wrap around occult symbols or are grasped by beasts, angels, or demons. In some cases, there are no panel borders at all, and several progressive scenes stretch across what would normally be a splash page (i.e., a page- sized single panel). This experimentation is taken to an extreme in Promethea #12, which is structured as one elaborate, multilayered 24- page comics panel.

Mr Moore, we say with respect, has the final word on his own work, through the mouth of Sophie Bangs: “I guess it’s where genius shades into madness.” Happy 25th Birthday, Promethea.

(1) “The Monstrous Alchemy of Alan Moore: Promethea as Literacy Narrative”, Studies in the Novel Volume 47, No.3 Fall 2015, John Hopkins University Press pp381-398

(2) “Alan Moore’s Promethea: Countercultural Gnosis and the End of the World” Gnosis: Journal of Gnostic Studies, 11 July 2016.

(3) If you get really lost, there are always these notes:http://tarothermeneutics.com/tarotliterature/promethea/PROMETHEA.pdf