Gun Honey

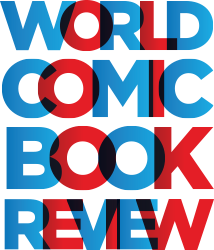

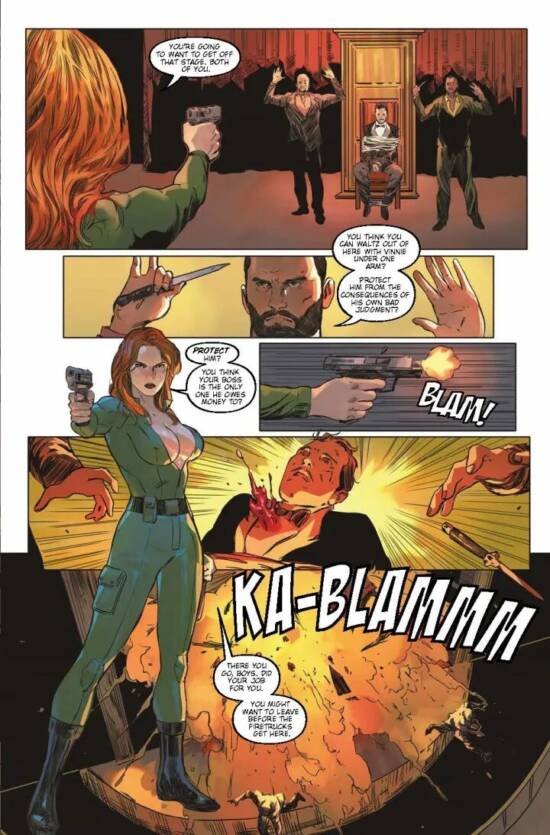

Writer: Charles Ardai

Artist: Ang Hor Kheng

Titan Comics, 2024

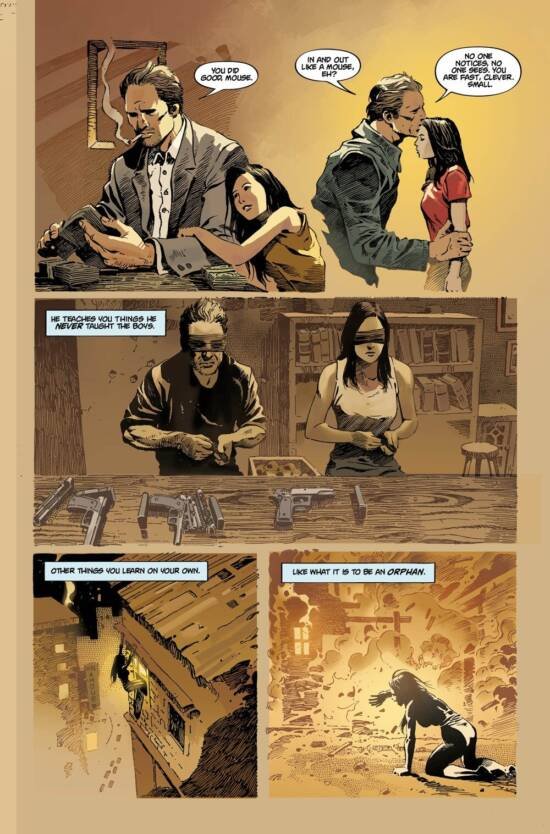

Queen & Country

Writer: Greg Rucka

Artists: Steve Rolston, Brian Hurrt, Leandro Fernandez, Jason Shawn Alexander, Carla Speed McNeil, Mike Hawthorne, Mike Norton, Chris Samnee

Oni Press, 2001-2007

This is a comparative review of two titles, Gun Honey and Queen & Country, which feature two characters who are in our view the opposite sides of the same coin.

Titan Comics’ promotional copy of Gun Honey, a crime noir comic written by Charles Ardai and drawn by Ang Hor Kheng, is brief and set out below:

The weapon you need, where you need it, when you need it – she’ll get it!

When a gun smuggled into a high-security prison leads to the escape of a brutal criminal, weapons smuggler Joanna Tan is enlisted by the U.S. government to find the man she set loose and bring him down!

Written by Edgar and Shamus Award-winning writer Charles Ardai – the founder of Hard Case Crime.

It was initially hard to know what to make of this title. It is very compelling but the main character, Johanna Tan, is mercenary in every sense. She has no lasting loves or causes. She is happy to supply a weapon to anyone, anywhere, for money. She flaunts her body as bait without any real need for intimacy or affection, has no remorse for the victims of crimes she helped facilitate, and in so far as she has relationships, they are all from a very bad crowd. Yet her background somehow makes her a sympathetic character. Johanna, under the bikinis and swagger, if we should look close enough, we should feel sorry for her. Like Tara Chace in Greg Rucka’s Queen and Country, which started publication almost 25 years ago, Johanna is emotionally fractured.

Gun Honey is very action-packed, filled with excitement, violence, danger, and sex. Carefully-laid out plans come together, or fall catastrophically apart. Johanna can read a room, blend into a background, or stand-out like a firework. Little wonder that a US government agency wants to recruit her as an asset. But Johanna is a seducer, not the seduced, and she has no inclination to be coopted into their schemes. And when she does agree to assist, the consequences for her manager are extraordinary.

Queen & Country is, perhaps, what might have happened to Johanna should she have been permanently recruited by a government agency. It is a quieter life, with more waiting, punctuated by sudden viciousness. Much of the tension comes from the discussions, the planning. Such is life it seems in the Special Operations Section of MI-6. The deskwork is grinding, and the process, amoral. In one of the stories, the adversary is the French government, which has deployed its spy agency to assist in winning a large commercial contract which will benefit the French economy. Erstwhile allies cut each other for money.

The main character, Tara Chace (known as “Minder Two”), is not as glamorous as Johanna. Each of the collected volumes of Queen & Country have quite different artists and quite different art. The first volume in particular with its cartoony art by Steve Rolston is very incongruous: Tara is on point as a sniper and the depiction of oversized cartoon eyes staring down the site of a sniper rifle is startling.

In the second volume, Tara is inexplicably dressed as if she is an extra from the pneumatic adventures of Danger Girl. But generally speaking, Tara looks like she is about to pop down to Tesco for some groceries. Her ordinary appearance are completely in contrast to Johanna’s revealing curves. Tara, like Johanna, however, views sex as transactional. For Tara, there is something dead inside. Tara seems sad about that state of affairs, but it is what it is. Whatever has snapped will not heal. And while Johanna is quick with sassy repartee in conversation with her shadow Agent Barrow in the first volume, Tara is noticeably tired, less than chirpy. For much of the series, her job is her life.

The supporting characters in Queen & Country are not thuggish henchmen or scarred villains like we see in Gun Honey. Tom Wallace is Minder One, and Ed Kittering is Minder Three, both likeable former servicemen. Some of them, however, are overweight, untidy characters with sagging waistcoats, who inhabit the shuttered offices of boring buildings in London. Yet they make brutal calls of life and death. Unlike the ethics of the characters, the story from beginning to end are black and white (representing a day, we suspect, when colouring comics for small publishers is not as technologically easy as it is now).

Johanna on the other hand is not the good soldier, obeying orders without question. She is, as it evolves, loyal to her family to the last. Questions of character lead to a very interesting conversation with Mr Ardai about Gun Honey. Here is the text of that exchange, set out in emails spanning the past few days:

WCBR: Joanna is a chess piece. She has always been the tool of someone, beginning with her father, and now a government agency wants her as its tool. She seems to be a product of her environment and unable to rise beyond it nor have closure on her family’s murder. Despite her skills and audacity, is it fair to say she has a weak character? Or is there something self-destructive about her, in that classic Fleming Bond-sense of a disregard for personal safety?

CA: I wouldn’t describe Joanna as weak or having a weak character – she left her home for the United States at 19, made a new life for herself in a new country without any connections or family to lean on, she built a reputation and earned respect in a deadly trade filled with unsavory participants (despite her gender, which surely helped her in some ways but was a disadvantage in others), and she did all this without becoming savage or utterly unprincipled. She decided she would earn her living in the field of criminal endeavor (where her skills lay), but she identified a line she wouldn’t cross, as a matter of personal principle, and until forced to kill to save her own life, she stuck to it. Is she self destructive? Yes. It’s not that she doesn’t care about her own survival – if there’s one thing she is, it’s a survivor – but she repeatedly puts herself in dangerous situations where there is an excellent chance she’ll get killed, and I think it’s got to be at least in part to prove something to herself, perhaps that she’s as tough, resilient, resourceful and capable as her father wanted her to be. She failed to save her father’s life (and that’s after her mother died giving birth to her), so I think she has acute feelings of guilt and failure she is trying to expiate. She has to live, and succeed, and thrive, as a sort of atonement for her family’s deaths, which she failed to prevent. She is constantly trying to prove to herself that she’s good enough, that she deserves to be alive. Is survivor guilt an example of weak character? I don’t think so. It’s a cruel goad and maybe a species of self-loathing, but I don’t think it’s weak.

Now, is she a chess piece? That’s a different question, and an interesting one. Her opponent in the second storyline explicitly says she is, but she’s trying to manipulate Joanna, and in the end Joanna gets the upper hand. I don’t think Joanna’s father manipulated or exploited her, he simply taught her the family trade, which happened to be crime; she was no more a chess piece of his than the son of a furrier who winds up working in the fur trade, or a grocery store owner’s kid who makes deliveries for the store after school. The government tries to recruit Joanna, but it doesn’t succeed – I won’t spoil the closing act of the first story, but rest assured that she comes out on top and the government agency doesn’t get anything like what it wanted out of her. If this is a chess piece, it’s not a very obedient one!

WCBR: The self-loathing and survivor’s guilt is interesting. You’ve cleverly incorporated the scene where Joanna’s father tells her to not be in the house at the time of the explosion. He was willing to sacrifice himself and his sons for whatever debt he had to pay that day, but he wasn’t willing to allow his daughter to die. That is going to skew any young child’s views on what is wrong and what is right in the world, especially a child who has already been trained as a thief. Is the line she won’t cross an artificial one?

CA: Yes – but the lines any of us choose not to cross are artificial, aren’t they? We like to tell ourselves that we’re guided by absolutes, but nothing is; the Ten Commandments are just something someone wrote down a long time ago, and so is Hammurabi’s code and the Hippocratic Oath and every law on the books. If we follow them out of fear of punishment, it’s a might-is-right matter, and if we follow them because we’re persuaded they make moral sense, it’s our own judgment we’re abiding by, not some external True North. Joanna learned young that she lived in a universe where there is no god (what benevolent deity would permit the slaughter of her family?), no rules but what she chose to follow, and so she crafted a moral structure for herself. In a lower-stakes way, her attitudes toward sex and nudity are as self-determined as her attitudes toward violence. Someone else – particularly other women – might unquestioningly follow society’s “rules” about the inappropriateness of showing their naked body or engaging in sexual acts, but Joanna sets her own rules, based on some combination of expedience and preference and a conviction that she is free to decide for herself what is and isn’t acceptable. She enjoys being naked and sees nothing wrong with it; she uses sex as a tool, freely and without hesitation; and she won’t restrict herself within society’s rules simply because society says they are rules. This is freedom in an existentialist sense. Or to use William Blake’s phrase, she won’t bind herself with the “mind-forged manacles” that others in society unthinkingly submit themselves to. Or to quote Hamlet, there is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so.

WCBR: Johanna then has a nihilist perspective on life and existence? It’s a compelling comic, action-packed and with enough realism to make it believable. Do you think Johanna’s “who gives a fuck?” attitude also has appeal to the audience?

Yes: I think readers enjoy reading about characters who do things, or live in ways, they might fantasize about but would never actually be bold enough (or unconcerned enough about the consequences) to do or try. I don’t think many of us would actually like to live a life of crime or derring-do, but it’s fun to imagine and to read about. And the same is true of a life where we say “I make my own rules, I live the way I want in the moment, and I defy anyone that says I shouldn’t.” In real life, we have jobs, bosses to answer to, family obligations, duties, responsibilities. We don’t throw that all away to fly to Corsica and lie naked on the beach. But it’s fun to experience that vicariously in a comic or movie.

WCBR: I mentioned Bond, and perhaps some people might think Catwoman, but it seems to me that there are plenty of other emotionally-neutered mercenary-type inspirations for the character: Molly in William Gibson’s Neuromancer, and the protagonist in The Day of the Jackal. Are there are other characters which have served as inspiration?

CA: The ones you mentioned were certainly somewhere in my mind, but one you didn’t mention is Peter O’Donnell’s Modesty Blaise, who was found as a young girl in a refugee camp and grew up to be a hyper-competent and sexually provocative weapons expert/criminal/secret agent. In some ways, I wanted Joanna to be a Modesty Blaise for the new century. I also had in mind Lawrence Block’s protagonist from SUCH MEN ARE DANGEROUS, Paul Kavanaugh, who is an alienated loner with an elastic sense of morality who does bad things for money but also has strong principles that he strives to live by. Parker, the hyper-professional master heist artist in the books Donald E. Westlake wrote as “Richard Stark,” also might have given a bit of his DNA to Joanna. And just on a practical, mechanical level, I was inspired by The Godfather, where Michael Corleone has to go unarmed into a deadly situation and find a gun hidden for him behind a toilet tank so he can come out blasting. Well, someone had to hide that gun there – who? We’re never told. But the idea that that had to have been some Corleone soldier’s job was fascinating to me, and I thought it would make an interesting profession for the main character in a crime series.

WCBR: I should have thought of Modesty Blaise myself. I had thought of Jinx, an immoral love interest in the 2002 Bond movie Die Another Day. But even Jinx worked for the NSA. Her violence was justified by duty to country. It seems to be that you have created a protagonist who is clever, sexy, determined, but not especially likeable. Is it possible to like a character like this? DC Comics have a similar character in the form of Cheshire. She’s smart, sexy, sassy, and the mother of Red Arrow’s child, but at the end of the day, there’s nothing to like or respect in her. Whereas Catwoman wants to be a better person. Joanna seems happy being a cause of misery.

Of course, you may be planning some epiphany for Joanna down the track and I’m giving you a headache by drilling into this issue!

CA: I think Catwoman does or doesn’t want to be a better person depending on who is writing her! This is the standard problem when multiple authors take turns writing the same character or an ongoing story (and maybe that applies to the multiple authors of the Bible as well, now that I think of it). I think Joanna is likable as a character even if in real life you might not enjoy having her as a friend, the same way James Bond wouldn’t be a great friend or even much fun at parties. She’s fun to watch get into and out of scrapes, and I think we like seeing her get the better of authority or figures in power, whether that’s the government or powerful criminals or a shadowy adversary plotting her demise. We’re on her side in those cases. If she used her talents to hurt the vulnerable and sympathetic she’d be truly unlikeable, but she doesn’t, or at least we don’t see her doing that. At the end of her most recent series, she’s planting a gun to take down Putin – not one to take down Zelenskyy. I’m not sure she necessarily would turn down the latter assignment, but if she accepted it, I think she really would be unlikeable, so I’m not going to let the story go that way, even if Joanna might.

WCBR: I see: Johanna sounds like the sort of friend who is good to drink with but not so good to give the house keys to. Is Johanna an underdog though, or just a lone wolf?

CA: Can’t you be both? She’s a lone wolf when no one is gunning for her, or she goes up against another criminal, one on one; she’s an underdog when the corrupt intelligence apparatus of the U.S. government is marshalled against her.

WCBR: One of the things which is most striking about Joanna is that she is prepared to deliver the weapon to a hit, but not actually use it herself. That process of facilitation cannot be to keep her conscience clean, because she does not have much of one. She will not press the trigger but will go to elaborate lengths to get a gun to the person who will press the trigger. Is this a manifestation of cowardice? She saw her father and brothers die in an explosion, and so at first I thought she was not prepared to take a life in a Batman homage, but then it becomes plain she will shoot it out if she is trapped in a corner.

CA: That’s right: she does shoot when trapped and her life depends on it. She’s not so principled that she’d die for this principle. But I think one way to look at it is that she only kills when she has a personal reason to (such as self-defense). The idea of taking money to carry out a murder on behalf of someone else is odious to her, maybe in part because it reminds her of the anonymous person who planted the bomb that killed her family. This wasn’t someone who had any personal grievance against the Tans, she simply accepted a payment to do it. And Joanna doesn’t want to lower herself to that level. But it is a sort of wilful head-in-the-sand posture for her to ignore the fact that the people she supplies go on to use the weapons she provides them in all sorts of terrible ways. Maybe she’s like the store clerk who says, “Maybe he only bought that ski mask from me because he has winter vacation plans; maybe he bought the carving knife for the Thanksgiving turkey.” Ultimately, the choice to use a weapon is on the person that makes that choice. But I think the answer in Joanna’s case is that this is what she was trained from childhood to do, it’s how she earns a living and more or less the only way she knows, and if she didn’t talk herself into finding it tolerable, she’d either have to start over from scratch again or starve. So she does it, and tells herself that at least she isn’t that worse sort of criminal who *directly* causes pain and suffering. She only indirectly facilitates it. And that helps her sleep at night, like the Mob accountant who says “I only keep the books, I don’t break the kneecaps myself.” Her hands are only clean on a relative basis. But sometimes you take what you can get.

WCBR: That reminds me a little of Maria in Deadly Class, towards the end of the title. She knows she could make a lot more money as an assassin, but she chooses to clean up her act and becomes a poorly-paid nanny and housekeeper. And it is clearly really hard – and brave – for Maria to be something other than what you’re trained to be. Is Joanna ever likely to settle down and be a parent?

CA: I don’t think Joanna would be a good mother. She’s too selfish. She would defend her child’s life fiercely and teach her to be strong and independent, but in the end Joanna would live the life she wants rather than placing her joys and desires second to those of another person. (William Blake again: “And the gates of this Chapel were shut,/And ‘Thou shalt not’ writ over the door…And Priests in black gowns, were walking their rounds,/And binding with briars, my joys and desires.”) Joanna not only refuses to submit to the black-gowned priests in society, she also lacks the black-gowned priests most of us have installed in our own minds. So no, I don’t see her ever settling down. I also don’t see her living into old age. She’s Achilles: she’ll burn brightly and briefly, and when the time comes, go down in flames — as on some level she knows she should have as a little girl, when the rest of her family did. Maybe in the end this is Joanna’s tragedy: she is defiant, proudly so, making her own way, all the world’s rules be damned…but the flames are always licking at her heels.

WCBR: That broad streak of self-destructiveness will be the end of her then. Do you think you’d ever write a conclusion to her adventures?

CA: I might. I’m not shy about bringing my characters’ stories to an end. But of course commercial considerations might intrude. As long as readers want to keep reading about Joanna’s adventures I might be reluctant to ring the curtain down. (Though I could always write her final adventure and then write prequels that pre-date it.)

WCBR: I haven’t asked you about the art. Ang Hor Kheng is indulging in cheesecake, but is handy with shadows, underscoring that Johanna is happiest slipping in and out of inky blackness. The art reminds me of Marc Silvestri’s work on Uncanny X-Men in the late 1980s. I find the facial expressions really interesting. It’s easy, I imagine, to draw gritted teeth or a frown because those facial expressions are immediately recognisable by a reader. But Joanna is often solemn, as if concentrating. We never see a smile. Is that deliberate?

CA: Ang is such a pleasure to work with – I describe a scene and then wait like a kid up early on Christmas morning to see how he draws it. (You say it’s easy to draw gritted teeth or a frown, but I can barely draw a circle or a straight line myself, so for me, everything Ang draws is a wonderful treat.) As for Joanna not smiling, I didn’t give Ang that specific instruction, but on his own he’s given her an intensity that I think suits the character well. His line reminds me of early Frazetta, and those barbarian girls didn’t smile much either. They had giant serpents to cleave. Joanna has her work to do as well. I’ve described her sometimes as Christian Bale to Dahlia Racers’ Tom Cruise (Dahlia is Joanna’s ex-girlfriend and the protagonist of the spinoff series HEAT SEEKER). Tom Cruise smiles; Christian Bale broods. Joanna is more of a brooder, I think.

**

Another difference then, between the two characters: Tara falls pregnant to Tom Wallace, and has a daughter, Tamsin, and her life completely changes.

Gun Honey is available on Titan Comics’ website: Gun Honey @ Titan Comics (titan-comics.com)

Queen & Country is, sadly, no longer in print. Second-hand issues are available on eBay.