Writer: Ben Aaronovitch and Andrew Cartmel

Art: Lee Sullivan

Titan Comics, 2016-2017

Writer Ben Aaronovitch has for around a decade penned a series of novels and short stories called Rivers of London, and in-between has branched out into graphic novels. There have been eleven graphic novels so far, and publisher Titan Comics has collected the first three as trade paperbacks in a stylish hardcover box. These first three are the subject of this critique.

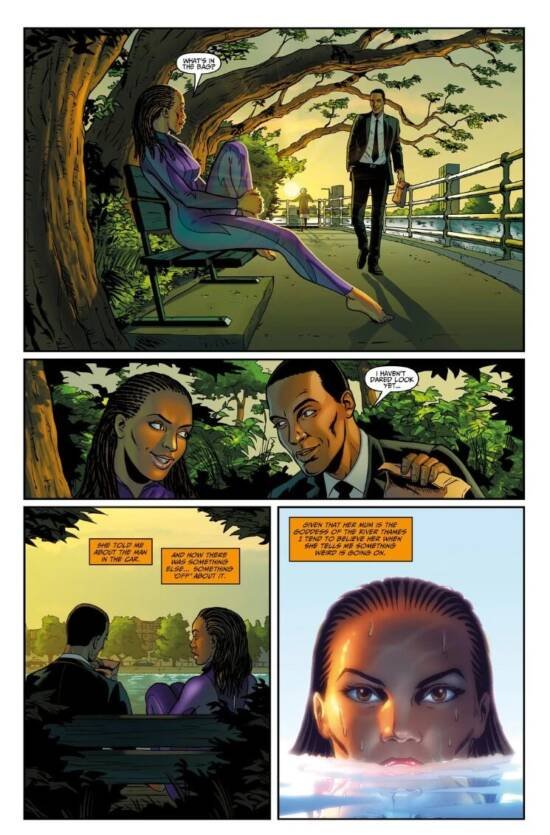

New participants to the continuity of Rivers of London (such as your reviewer) will find the plunge a little disorientating. There is not much of an introduction, and it is not obvious from the comics why the title has its name. There is one featured character who is the manifestation of a river – Beverley Brook, a tributary of the Thames. But otherwise, all other rivers of London (according to Wikipedia) belong in the novels.

Beverley Brook is a beautiful, vivacious girl with bad housekeeping skills and the power to enchant men (including Russian gangsters). She spends a lot of time in water, but inexplicably wears a blue wetsuit when she is in the river (strange garb for a water goddess). Beverley is the girlfriend to a police officer, “pretty” Peter Grant. Peter is not just any policeman: he is a trainee wizard working within a special branch of the London Police called “Falcon”, or more diminutively, “The Folly”. Peter is the apprentice to a man named Thomas Nightingale, who is a genuinely powerful wizard with 1930s sensibilities – there are no flowing beards and pointy caps, but instead Nightingale sports a well-cut two-piece suit and conservative, slicked back hair. Nightingale runs The Folly, and appears to be immortal. Nightingale’s maid, Molly, is altogether too handy with a knife, cannot speak, and has the temperament of a wolf. Filling out the main cast is Sahra Guleed, a “regular cop and self-professed Muslim ninja”.

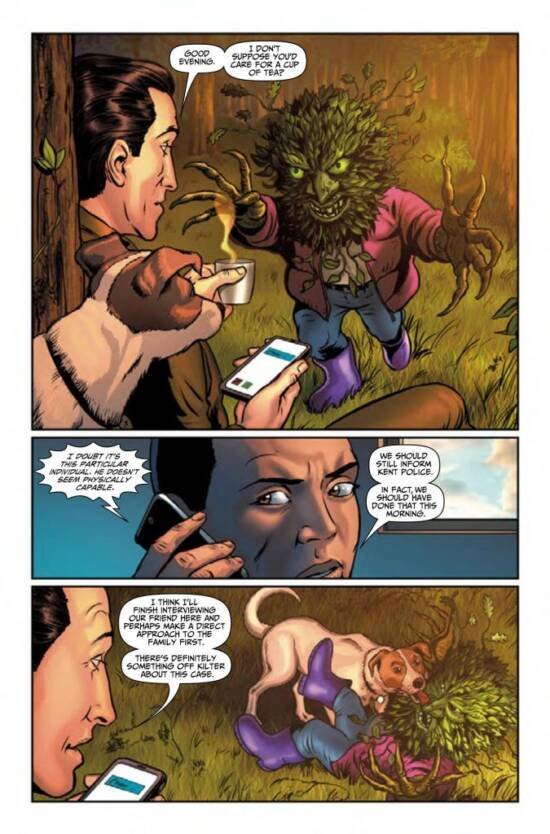

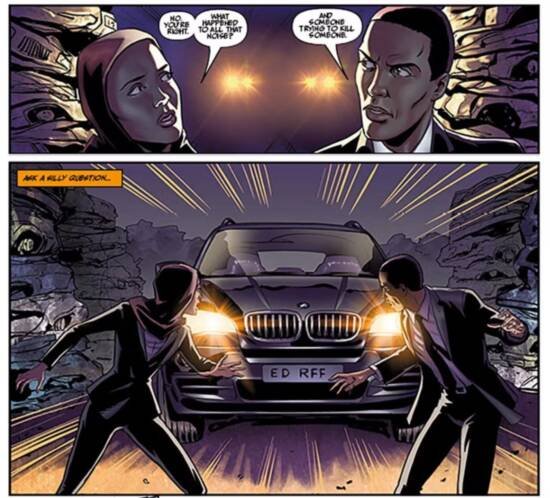

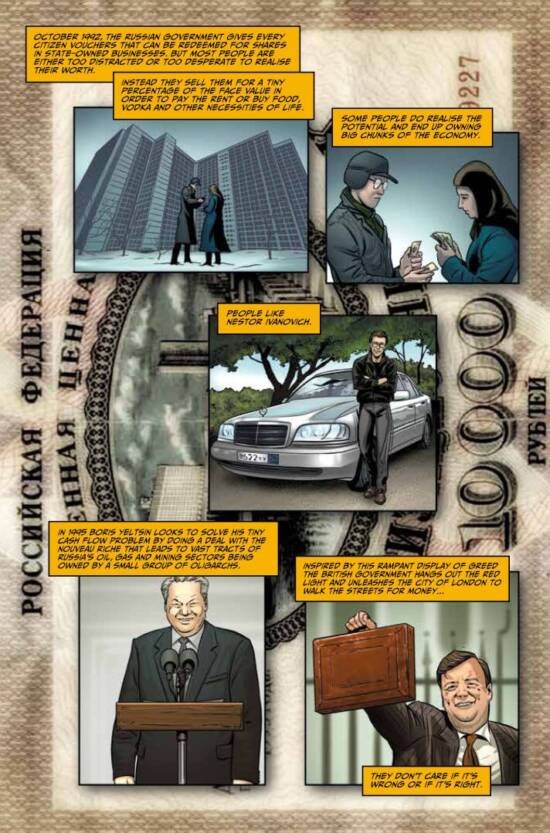

Master-and-apprentice wizard relationships sound very Harry Potter, but Rivers of London is instead very much a series of detective stories. The team in these three collections deal with the criminal legacy of sorceresses who served in a special brigade in Stalin’s army, some BMWs who kill people and are haunted by the vengeful ghost of a drowned 16th century witch, and slime mould animated by the spirit of a voodoo musician. Each of these stories are presented with a comedic overlay which negates the potential for cheesy melodrama.

The tactic of slightly absurd humour balancing impossible danger is unsurprisingly reminiscent of the BBC science fiction series Dr Who – Mr Aaronovitch was a writer for the Doctor’s adventures. Rivers of London does not take itself too seriously, best evidenced by the murderous BMWs (we are reminded of the 1960s cult motion picture, The Cars Who Ate Paris).

London is the backdrop for the stories in the three trade paperbacks, and people familiar with the city will recognise many of the locations from Lee Sullivan’s pleasing art. (There is even a joke at Southwark’s expense.) While these stories could easily dovetail into one of Londoner Warren Ellis’ projects, such as Planetary (“the archaeologists of the unknown”) or even the catastrophe-averting team in Global Frequency, Rivers of London lacks any of Mr Ellis’ trade mark acerbic and borderline objectionable characters. Instead, as with Dr Who, each of the protagonists are positively likeable. Those who are not, such as the horrible and racist Mr Wellcome Sr, suffer somewhat satisfying deaths. Perhaps a better shared universe would be Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere, in which the characters meander through a hidden London. Even Mr Gaiman’s The Sandman would easily amalgamate with Rivers of London: tales of magic, immortal beings, arcane rules and protocols… we would not have been too surprised to have seen Mr Gaiman’s Mad Hettie stumble out from the shadows. This musing of possible crossovers conveys our view on who the target market is for Rivers of London: readers who enjoy mysteries sitting right beneath our noses but magically outside of our line of sight.