Creator: Milo Manara

Fantagraphics, December 2024

In June 2010, news outlets reported that scientists discovered the bones of the Old Master best known as Caravaggio. They were found in a built-over cemetery in Porto Ercole, in Italy. Caravaggio was endeavouring to make his way back to Rome to beg the Pope’s forgiveness, but died of a combination of lead poisoning, heatstroke, and butchered wounds from a sneak attack which had not healed.

Here is the promotional copy for this title, published in December 2024:

Discover the bawdy, swashbuckling life of one of the greatest painters in history through Milo Manara’s passionate and personal tribute to his artistic idol.

Caravaggio: The Palette and the Sword Book 1 is the first half of Milo Manara’s two-volume epic biography of the hot-tempered Italian master painter. It depicts Caravaggio’s early years in Rome as he struggles to capture truth on canvas, only to have his art condemned to be burned by the Church. He then is forced to flee the city when he kills a man in righteous fury over the death of a prostitute.

The two volumes of Caravaggio mark the return of Manara to U.S. readers and the debut of Fantagraphics’ new series, The Milo Manara Signature Edition, featuring affordable paperbacks of maestro Manara’s internationally acclaimed work. (Book 2 will follow in Spring 2025.) Discover the bawdy, swashbuckling life of one of the greatest painters in history through Manara’s passionate, personal tribute to his artistic idol, Michelangelo Merisi, whom the world would come to know as Caravaggio.

In May 2010 your reviewer was in Rome enjoying a doomed and tempestuous summer fling. My then-girlfriend had heard from a friend that there was a Caravaggio exhibition on in Rome: a remarkable one, with all of the painter’s major works. I had never really heard of Caravaggio. In fact, in one conversation, I muddled his name with “Carpaccio”, to the snooty frustration of my romantic partner.

There was a queue to get into the Scuderie del Quirinale, which took an hour and a half to churn. It was a long wait on a glorious balmy night, and as I shifted my weight from foot to foot I marvelled about the cosmopolitan tendencies of the Romans. The exhibition celebrated the 400th anniversary of Caravaggio’s death. It attracted 580,000 visitors.

Bernini was influenced by Caravaggio. From a previous tour of the Louvre I knew I liked Bernini and his chiaroscuro. So, I expected a long room full of wonderfully rendered portraits of dead aristocrats in shiny black armour: the modus operandi of Bernini.

When I finally entered the gallery, I fell in love with The Card Sharps. Caravaggio did more than his fair share of grand scenes from the Bible. But it was this painting which caught my breath. It was an insight into the common life of 17th century Rome, a rough and tumble place. The painting was not the Virgin Mary or Aphrodite or the Spanish royal family (Velasquez, in the Prado). It was a picture of two card cheats, and the scam of their stupidly oblivious target. The artist was taking the piss, as we Australians say, out of the victim. And he has painted his own face into it, along with the face of his protege (and possible lover), Minetti.

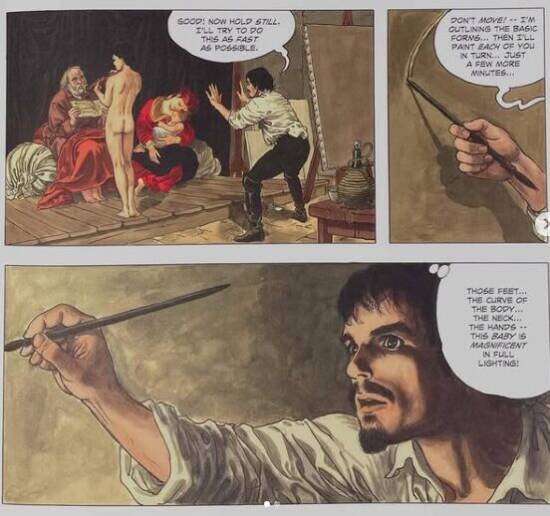

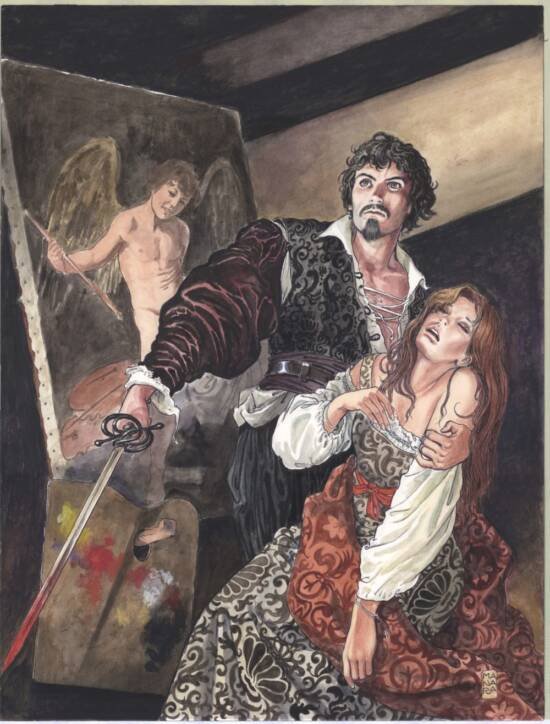

When we read American superhero comic books, we talk positively about the skills of the artist. “That Jim Lee, look at that cross-hatching.” Or, “I love the photo realism of Alex Ross”. Or, “Frank Cho lines masterfully.” But none of these people are Old Masters. One of the purposes of this comic surely was to introduce the comic book reading audience to one of the best of them. Creator Milo Manara’s art carries half the story. Caravaggio’s brutal nature, exacerbated by lead poisoning, and given dialogue by Mr Manara, carries the other half.

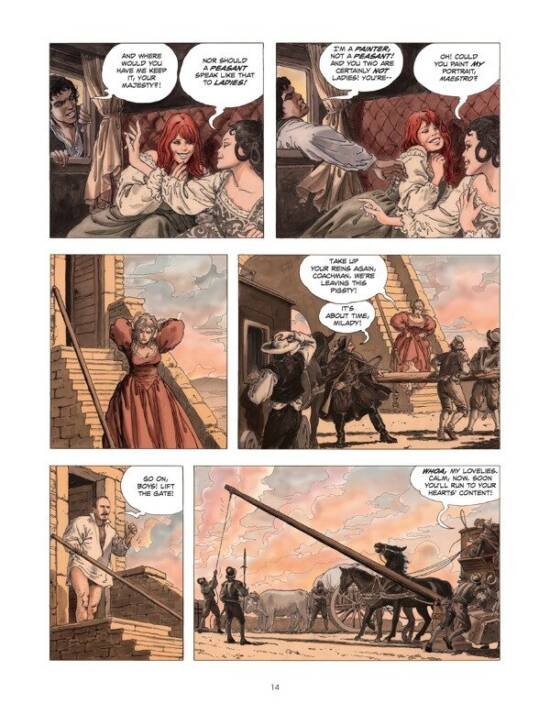

Mr Manara is best-known for his X-rated comics, some of which have appeared in English language publications such as Heavy Metal. Mr Manara usually draws pretty girls, and usually pretty girls having sex. We see sex in this title, repeatedly. If it is sordid, it is because the Rome of Caravaggio’s day was grimly sordid indeed. It was a holy city in name only. Young girls might be prostituted by their mothers by the age of eight. The punishment for prostitution and other crimes was vicious – being repeatedly struck upon the buttocks by a jagged metal tool. Roman prisons were dark, looming, and dangerous places.

The attention to historical detail in this title is excellent. Mr Manara is assisted by the well-catalogued records of the day. They spell out Caravaggio’s crimes. A waiter who questioned his taste was rewarded with a plate of artichokes in the face; a man who insulted Caravaggio behind his back was in turn attacked from behind with a sword. Caravaggio made a hole in the ceiling of his rented studio, so that his huge paintings would fit inside. (Mr Manara too briefly touches upon this outrageous episode.) Caravaggio’s landlady sued, so he and a friend pelted her window with stones. Caravaggio mixed with bad company: he had an extended feud with a pimp named Tomassoni. We meet the villainous Tomassoni early in this title. Once he had influence within the establishment, Caravaggio swaggered about town carrying personal weapons without permission. Mr Manara depicts ecclesiastical authorisation for Caravaggio’s armed status, but as far as we know that is not clear from records.

One technical inaccuracy is Caravaggio’s appearance. Caravaggio is unlikely to have been a handsome man. His self-portraits show a sullen, doughy face, but Mr Manara has Caravaggio say he painted himself in this way, so he could not be accused of vanity expressed within his work. Mr Manara’s Caravaggio is instead often drawn as a beautiful swashbuckler.

This first issue of Mr Manara’s series ends with Caravaggio’s famous duel. Recently discovered documents give a new interpretation of the May 1606 melee. It was arranged in advance by eight participants, but Mr Manara depicts it as a spontaneous brawl.

Caravaggio and his three companions, one a captain in the Papal army, met their rivals at a pallacorda court in Campo Marzio, where Caravaggio lived. (Pallacorda was a type of tennis, played with a ball with a string attached.) Mr Manara depicts the fight as being triggered by the suicide of his occasional model and lover, Annuccia, but the text of the court report suggests the fight broke out over a gambling debt. Caravaggio killed Tomassini and fled the city. One of Caravaggio’s own supporters was seriously injured. Mr Manara sadly reduces this down to two pages.

We do not criticise Mr Manara at all for his selection of fact. The Old Master’s history is a palette with colours to be chosen that work to help tell the story. Mr Manara does more than fair justice to the subject matter.

What is next in the series? Taken to prison, Caravaggio was subsequently put on trial, bribes his way out of jail with the help of an eminent family in Naples, and makes his way to Malta, where his adventures become very dark and strange indeed. We very much look forward to Mr Manara’s next instalment.